I’ve had hit-or-miss success in 2016 with Bible memorization. It’s entirely possible I’m being too hard on myself, but I also know I struggle to consistently work at the parts of the Bible I’m trying to memorize this year.

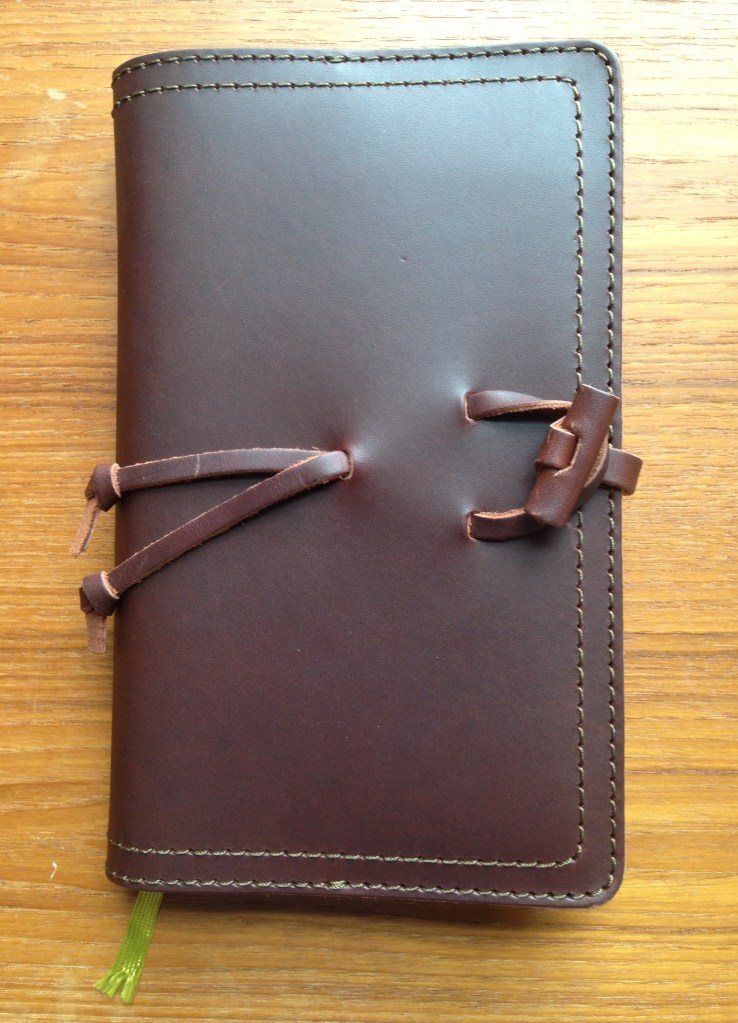

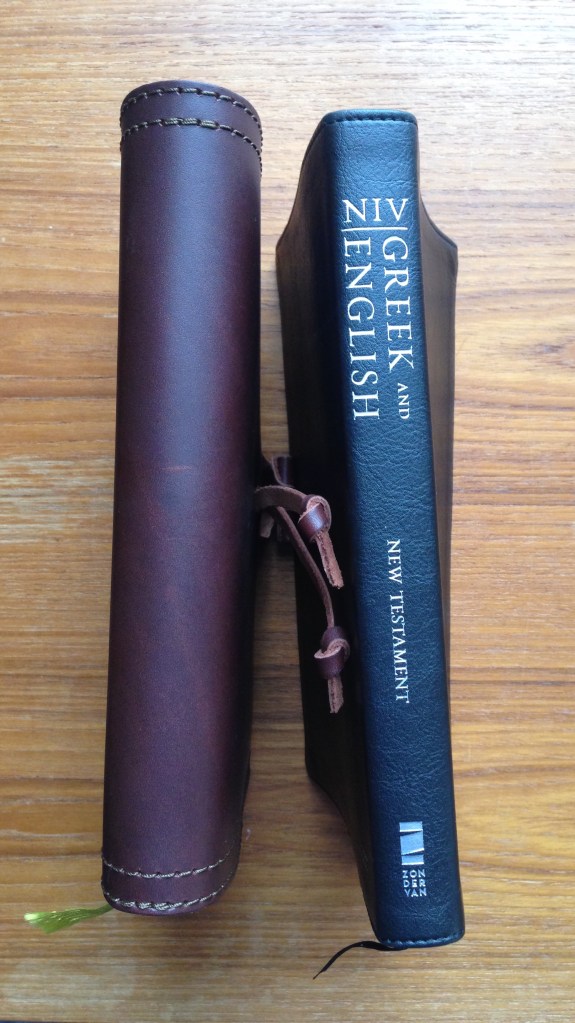

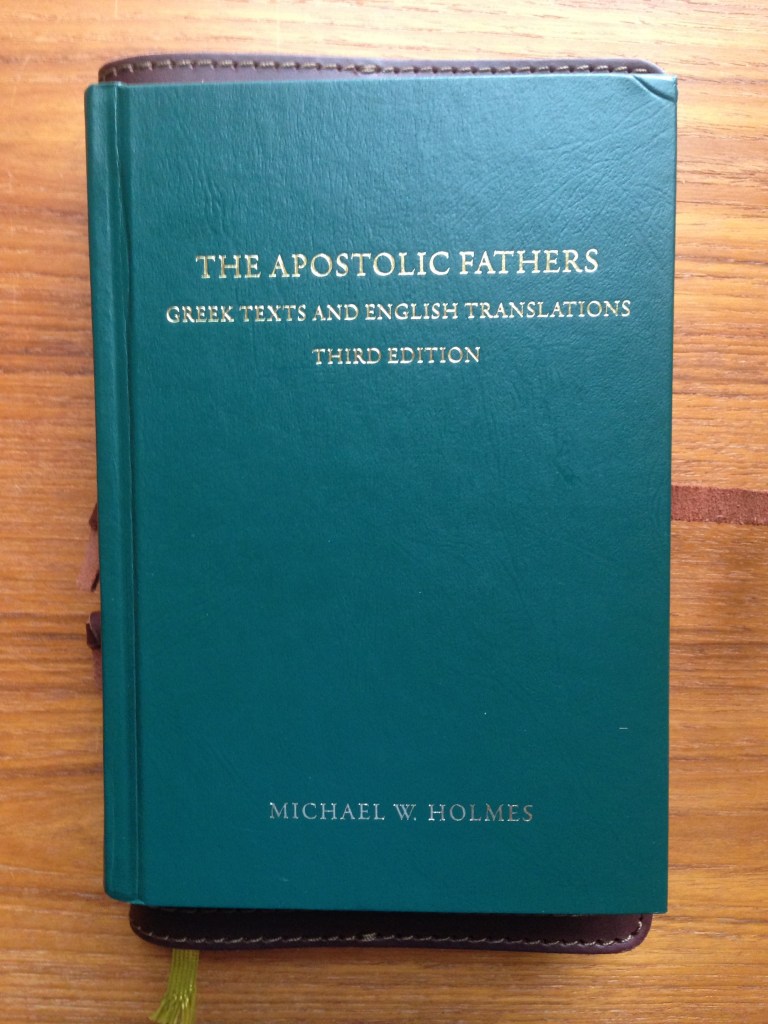

A tool won’t necessarily make me a better memorizer, but thinking it could help, I sprang for the Saddleback Leather Gospel of John Bible portion. You readers of this blog know I like good leather. You know I like pocket notebooks. And of course I like pocket notebooks with leather covers. So why not have a portable Scripture portion covered in leather?

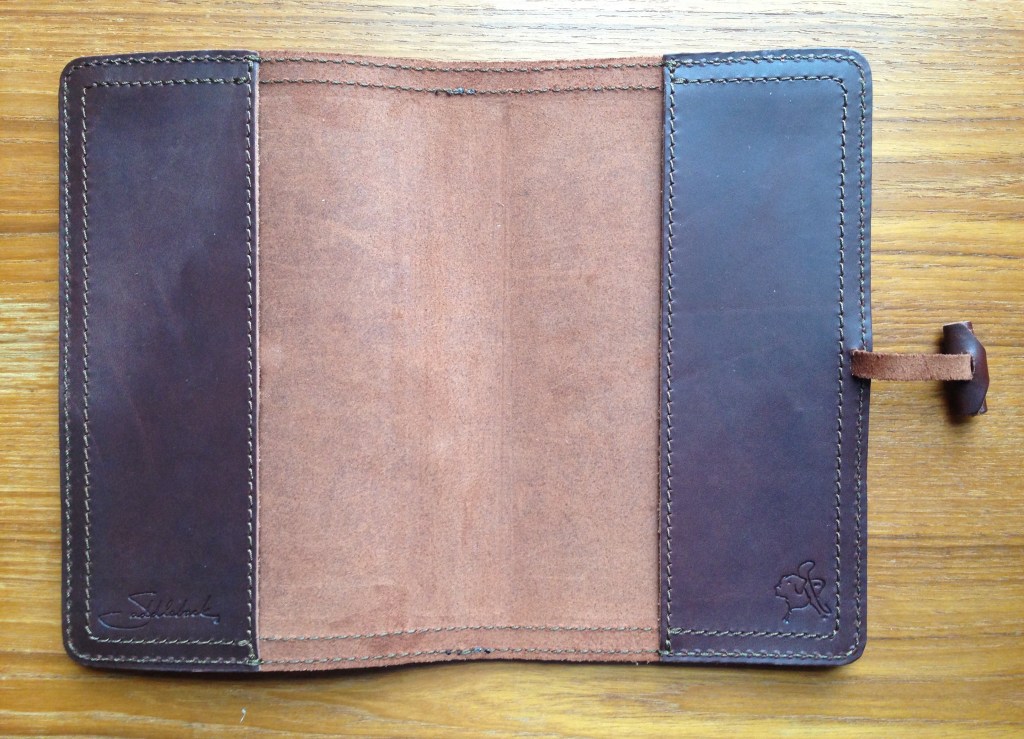

This has actually been a desideratum of mine for some time, so I was really excited to see that Saddleback Leather has just released a set of three books of the Bible (John, Proverbs, and Revelation), each stitched into a leather cover. These are not inserts that can be exchanged–they are permanently stitched to their covers.

Lemme show you.

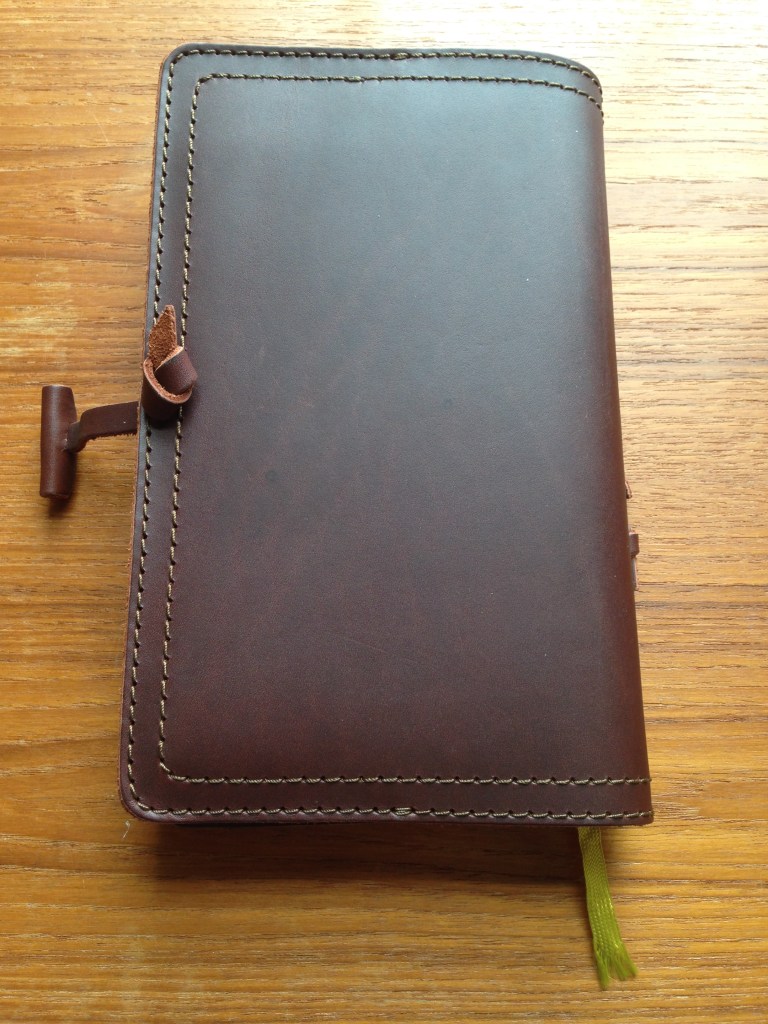

The book is passport size (think 3.5″ x 5″ Baron Fig Apprentice rather than 3.5″ x 5.5″ Field Notes or Word. Notebooks). This means it’s a great front pocket fit.

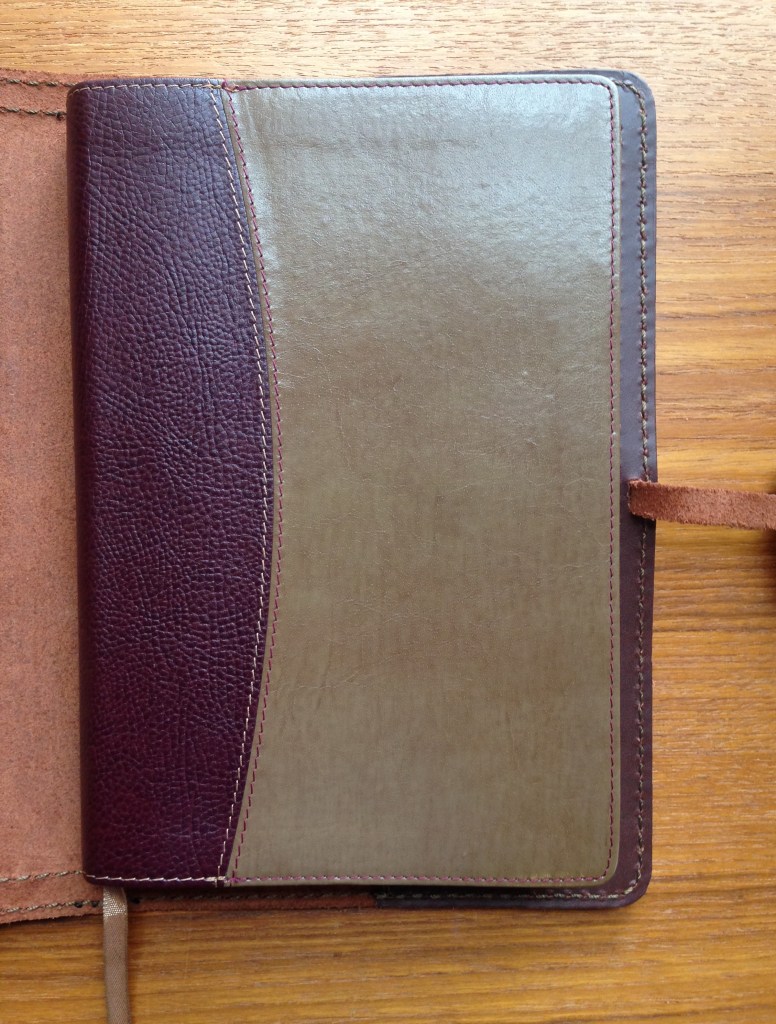

Here it is, front and back:

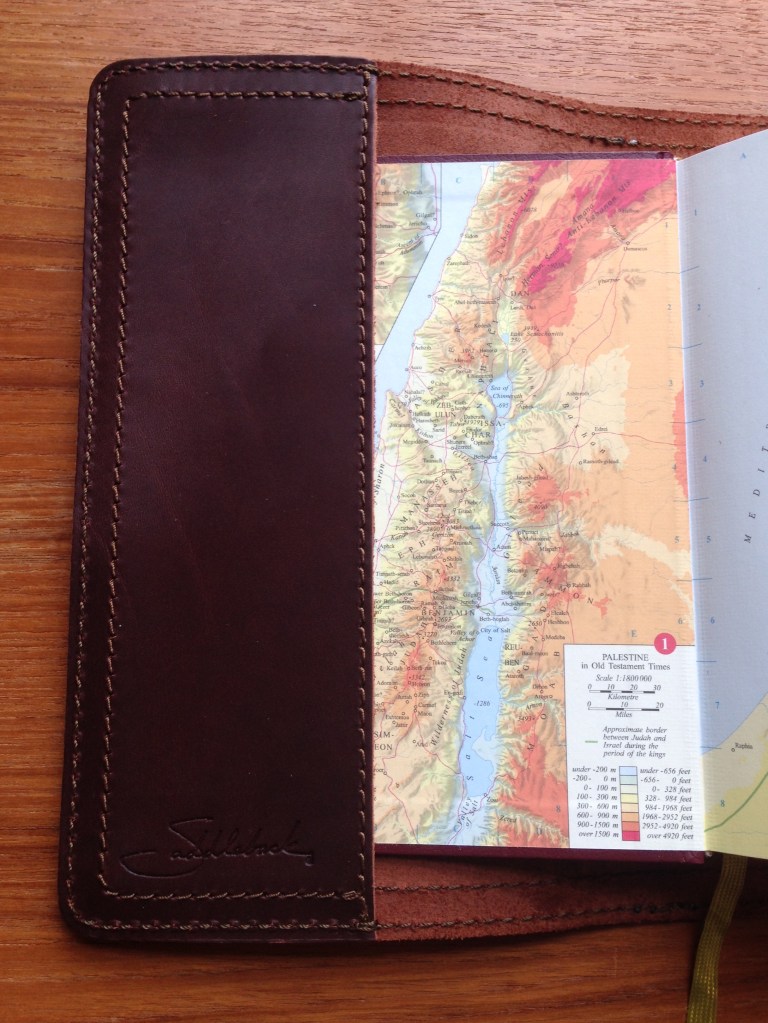

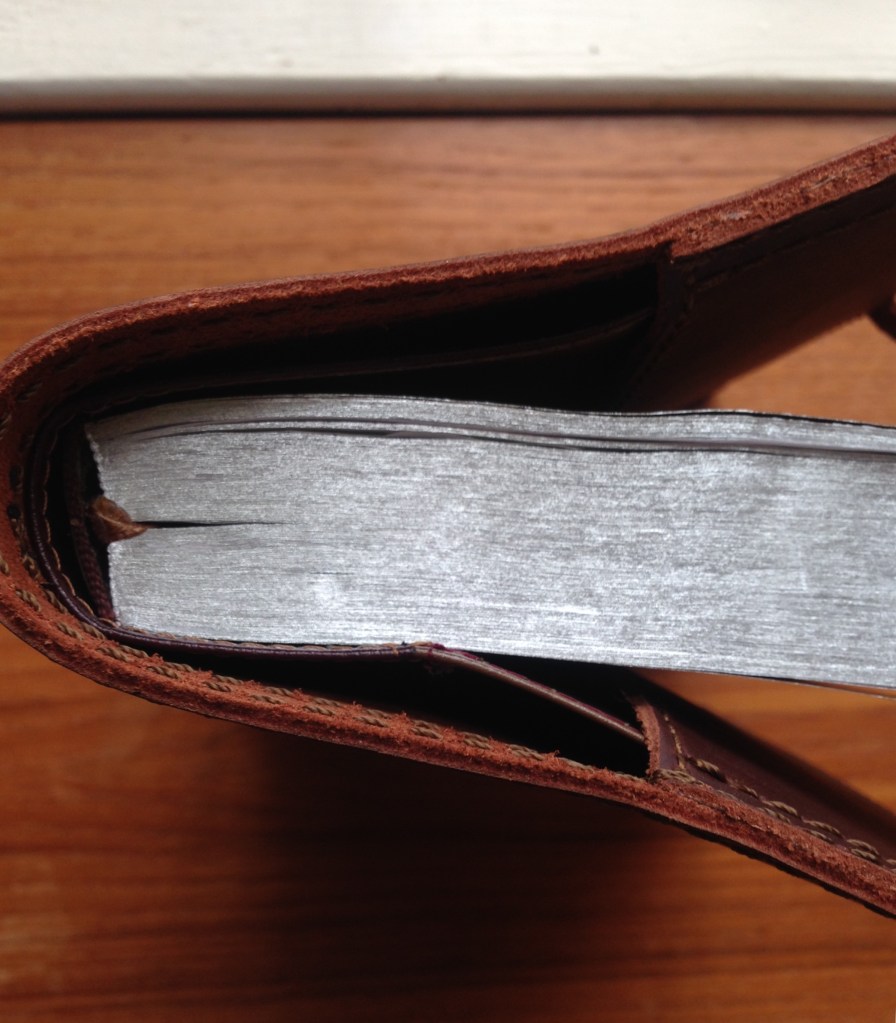

Here’s a look at how the uber-tough paper is stitched into the leather:

That paper, by the way, is “YUPO synthetic paper: 100% recyclable, waterproof, tree-free, durable, and easily wipes clean.”

Bible production is notoriously challenging, and I’m quite sure this piece was no exception. A bummer is that there is virtually no margin to the pages. The font is small, but the lack of white space is the larger issue:

This especially becomes a problem as some pages don’t lay 100% flat:

The leather is full grain and wonderful, as with all of Saddleback’s stuff. It smells good, of course. It will last forever. The paper looks just as tough, too. I don’t quite feel like trying to rip it to see if it’s truly tear-free, but it’s the kind of paper you could take on a camping trip and not have to worry.

Surprisingly, given the excellent workmanship on Saddleback products, the leather stitching was a little crooked, even though it’s machine-stitched:

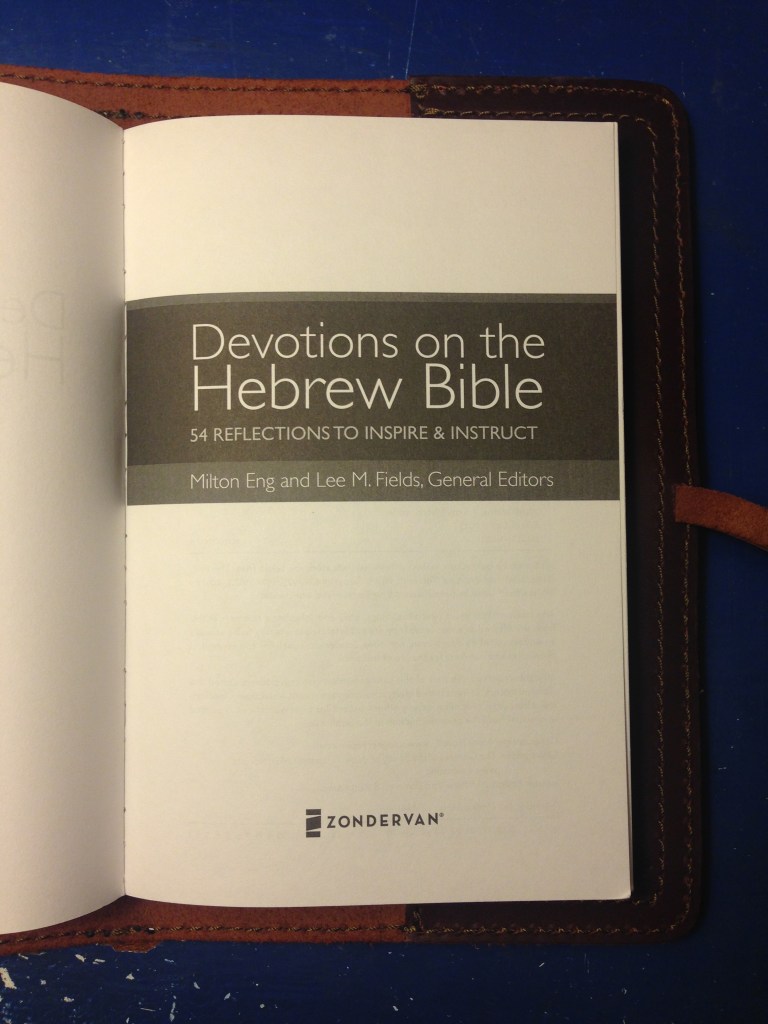

The insides are the NET Bible, which I appreciate as a translation for its rich footnotes. Those are not included here, which is inevitable, since the font is already small to get John to fit in.

There are 30 pages (15 sheets), including–oddly–five blank pages at the end, which means that one less sheet could have been used. (Maybe these are for notes?)

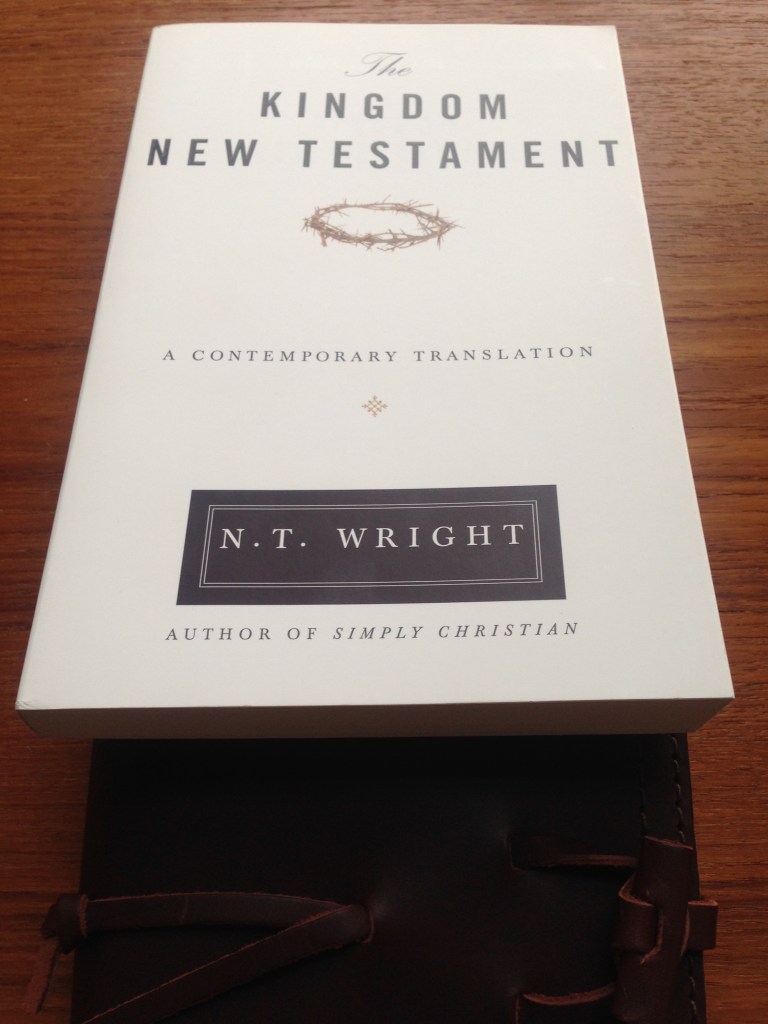

Back to why I got this thing–to memorize. The NET Bible does not lend itself well to memorization. Consider John 1:1-5 in the 1984 NIV:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not understood it.

Here it is in the NET Bible:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was fully God. The Word was with God in the beginning. All things were created by him, and apart from him not one thing was created that has been created. In him was life, and the life was the light of mankind. And the light shines on in the darkness, but the darkness has not mastered it.

I dislike the translation of the generic Greek ανθρωπος as “man” in the 1984 NIV. “Humanity” or “humankind” is better in 2016–even the NET footnote cedes this option, but the text alone just gives you “mankind.” And though the footnote in fuller NET editions explains “the Word was fully God” well, NET has other such turns of phrase that make the version less than ideal for memorization.

There are also no paragraphs in this text. This means the 71-verse John 6 is a single paragraph in the Saddleback Leather Gospel of John. There is a single blank line between chapters, but especially with those five blank pages at the end, could not paragraph separations for greater readability have been employed?

One more minor production quibble: the cover text (“The Book of John”) is ever so slightly left of center, and the branding on the back is a little off-center. These are not really noticeable (like the stitching is), and maybe it’s just that I’ve come to expect near perfection from Saddleback!

I still, however, think it is absolutely awesome that Saddleback is making these things, so even though the NET Bible here isn’t quite the pocket-sized, leather-covered panacea I was seeking for Bible memorization (I know: I have issues), I would still buy this again, even if only to support the effort and have it to keep with me.

I imagine the production of these little books will only improve in time–if you’re going to get one, maybe give it a couple months and see if the next few production runs iron out the quality and layout issues.

(Personally, I’d love to see an easier-to-memorize version available in the future, too, like the NIV or NRSV.)

Saddleback’s site is here, with many wonderful leather things. You can also check out my review of their pen/sunglasses case as well as their leather Bible Cover.

Here is the Gospel of John via Saddleback, as well as a larger set of three books of the Bible, similarly bound.

This was not a review sample–I paid for it, but was fortunate to have received a handsome discount code (as a newsletter subscriber) for the item.