There was a family with twin boys. They looked exactly alike, but everything else about them was different. One liked rap; the other listened to country music. One always thought it was too warm in the house; the other thought it was too cold. And so on. One brother was a hope-filled optimist, while the other was a convinced pessimist.

Their dad wanted to try an experiment with them. So one Christmas Eve, while the kids were asleep, he filled the room of his pessimist son with every single item on his wish list: toys, games, books, gadgets.

The room of his optimist son, on the other hand, he filled with horse manure.

Christmas morning came, and the Dad went to the pessimist’s room. That son was surrounded with his new presents, weeping.

“Why are you crying?” said the dad.

The son replied, “My friends will get jealous of me; I’ll have to share; there’s all these instructions to read before I can play with the toys; the batteries are going to run out…”, etc.

Down the hall the father saw his other son–the optimist–singing and dancing around in the pile of manure.

“Why are you so happy?” the dad asked.

The optimistic son said, “Because… there’s got to be a pony in here somewhere!”

Setting the Stage: The Tomb

The disciples on Easter morning lived in a pessimists’ world, and for good reason, as we’ll see. They had no hope of finding a pony among the manure. Their hope, they thought, lay dead in the ground, sealed behind a heavy stone.

Luke tells us some female disciples went to the tomb, “taking the spices that they had prepared.” They were going to embalm the body. Not in the hopes of resuscitating it—nobody thought that was possible. But because they wanted to show honor to the dead.

But they get there, and—no body. Luke 24:4 says “they were perplexed about this.”

And wouldn’t you be, too?

This is not necessarily a sign of hope to them, that the body is gone. It’s cause for despair.

Their beloved teacher, their companion and friend, the one who was going to redeem them from their constrained existence under Roman rule—this one was dead. What’s worse, they can’t mourn him properly now. They’re losing access to their chance at closure. This is not shaping up to be a good death.

Fact is, it’s not shaping up to be a death at all.

The angels ask, “Why do you look for the living among the dead?” (“The living,” they must’ve responded?)

“He is not here, but has risen!”

Spinning as their heads were, verse 8 represents at least a minor miracle: “They remembered his words.” It all clicks. Jesus is alive! They believe it.

And they run and tell the disciples and a bunch of others.

Unbelieving Disciples: Idle Tale

And don’t you just love how true-to-life the Gospels are?

The eleven apostles and the others—a formidable group of men and women from whom the Church would spring–they didn’t believe their own friends! Verse 11 says, “But these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them.”

“An idle tale.” Silliness. The ravings of madmen, or, in this case, madwomen. The narrator Luke was a doctor, his word for “idle tale” is rooted in medical language–it has to do with delirium. The women were assumed to be delirious.

Bad start for the Church

This is a bad start for the church–resurrection is THE core belief of Christianity. The apostle Paul would soon write, “If Christ has not been raised [from the dead], our preaching is useless and so is your faith.” (1 Cor 15:14)

Useless. The faith of these disciples the women are preaching to is useless. If the story had stopped here, you and I would not even be gathered for worship this morning! If you don’t have the resurrection of Jesus, you don’t stand a fighting chance against the world!

This is a real struggle of people of faith: they thought they were hearing idle tales.

They might have appreciated the narrative arc of the women’s story. They might have said, “This will make for some great literature to be studied in future English courses.” (Or, uh, Aramaic and Greek classes.) They maybe even saw the book sales potential–finally we’ve got something that can bump Homer off the best-sellers’ list!

But still, this is just a story we’re hearing, they thought. Fiction–not factual truth.

Justified, though?

One reason they didn’t believe the women is because of some bad cultural mores that discounted a woman’s witness. They weren’t seen as credible sources.

But if we can’t forgive the disciples their outdated sexism, let’s cut them some slack, for some other reasons. Before Jesus would undo death, his death had undone everything for the disciples. Every word Jesus had spoken to them? Felt like an empty promise. This coming Kingdom of God? Gone, nailed to the cross with him.

Besides that, one of these women, Mary Magdalene, had been demon-possessed. And not just sort of demon-possessed. She was severely demon-possessed. Luke told his readers earlier that she had “seven demons cast out.”

The disciples thought she was delirious, and must’ve wondered–did she now have a relapse, with Jesus dead? Is she a conduit for demons again?

Make no mistake–the disciples believed in resurrection, even before they saw Jesus. But the story of Lazarus notwithstanding, they seem to have reverted back to their default religious belief. Resurrection would happen in their mind… but at the last day. In the end times. And THIS was not yet the last day.

How we are like them

The story of the resurrection did not ring true in the disciples’ ears. To their mind there was no power to it.

There is a danger that you and I would hear the resurrection story as they did, as an idle tale. We are susceptible to the same disbelief the disciples had, when it comes to Jesus’ rising from the dead. Many today take this account as fiction.

Or worse, we might accept the truthfulness of Luke 24, but then unwittingly dismiss the resurrection story as an irrelevant tale. We may celebrate the resurrection historically, as a past event, without the realization that it still means everything for us today. We would be without true hope if we acknowledged that it happened, but then failed to live like ones who have ourselves received the gift of resurrection power, of new life.

Peter: Sprint to the Tomb

Peter fares a little better than the others. He actually takes the women’s story seriously, and so runs to the tomb, in Luke 24:12: “But Peter got up and ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen cloths by themselves; then he went home, amazed at what had happened.”

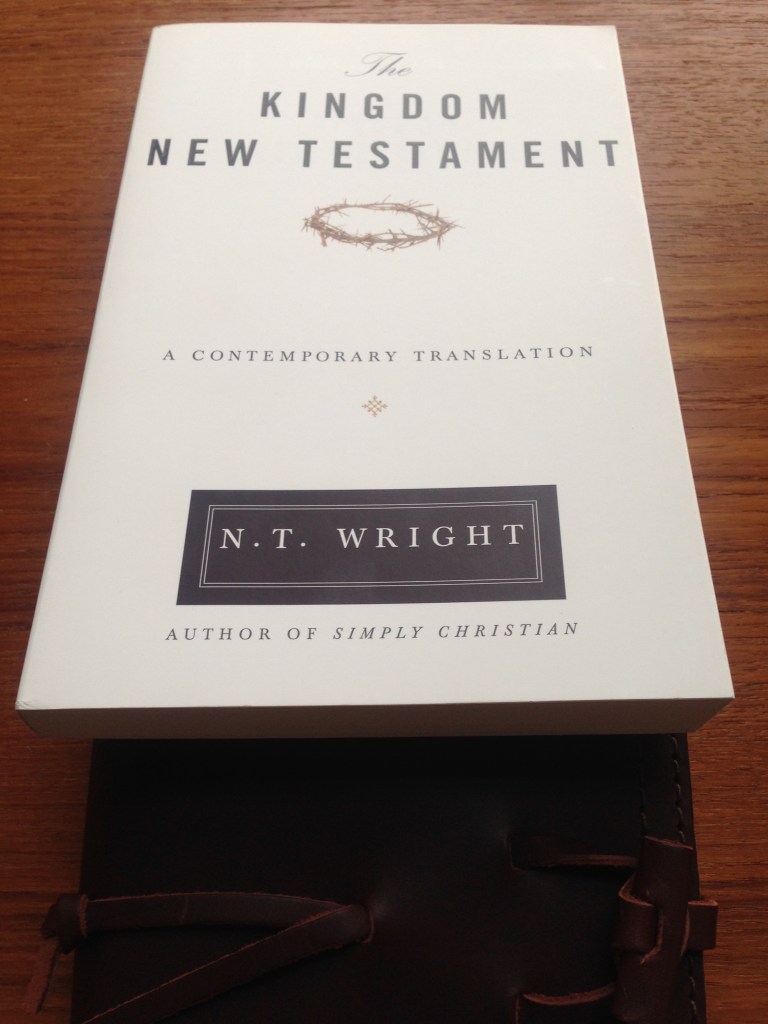

He gets there and sees the tomb:

But Peter goes home. He doesn’t, oh, say, go back to the disciples and confirm the account of the women. That’s because, even though he’s amazed, he’s still not sure what everything means. His amazement does not seem to translate into full acceptance of faith. It’s more like being perplexed, bewildered. He is astounded, yes, but this going home feels like a shrug of the shoulders.

We can identify with Peter. How many times have we sprinted towards the cross, only to get there and turn around and go back home, to our old ways? How often have we run towards the empty tomb, eager to meet our risen Lord… only to walk away as if nothing ever happened?

It’s like the one in James who looks in a mirror and then goes away and forget what he looks like. Peter’s response calls to mind the seed that was sewn, and grew up fast… but then could not grow once it encountered the thorns and weeds of this life.

Living in the light of the resurrection is more marathon than sprint. Eagerness is good, yes, but so is stick-to-itiveness.

The Women

We come to Jesus much as the women came to the tomb that morning. We come to him with no hope in the world, apart from what we trust he can give us. Maybe you’re coming this morning and wondering if the resurrection really is all that relevant to what you’re going to have for lunch in a little while, or what your working day tomorrow looks like. Maybe you are having trouble connecting the glory of this morning to the mundane week that awaits you. Perhaps you are looking for somewhere trustworthy to place your belief… someone Good you can hold onto.

Mary Magdalene and the others, desperate and forlorn, manage somehow to offer a model response to the resurrection.

The male disciples–even Peter, the so-called “rock”–are Luke’s version of the TV show “What Not to Wear.” Dismissing the resurrection as an idle tale? Not the response I’m looking for, says Luke. Sprinting toward the empty tomb, only to go away shrugging your shoulders in bewilderment? Nope.

Instead, Luke traces an inspiring movement of faith by Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James.

They looked for the living, albeit among the dead

The angel asks, “Why do you look for the living among the dead?”

The women didn’t realize they were looking for the living, but they were looking for Jesus all the same! They thought they were going to find a dead Jesus, but at least they were seeking all the Jesus they had left!

Especially in those moments when Jesus seems distant, disconnected–or, worse, dead to us–approaching what we have of him may be all we can do. Still do it, Luke suggests.

They bowed in worship

In response to the angel, the women “bowed their faces to the ground” in worship. This humble posture of Doxology shows their openness to letting God reveal himself however he will reveal himself. At this point they’ve let go of the fabrication that we know better than God.

They remembered his words

From their posture of worship, Mary and the women could remember what Jesus said. Verse 8 says, “Then they remembered his words.”

Remembering is not just something you happen to do or don’t. Sure, if we don’t go grocery shopping with a good list, the pack of coffee filters will slip our mind. But this remembering the women do–it’s more than a fleeting thought that happened to come to them. They’re training their focus back to inhabit the world they had known with Jesus. They’re calling his words to mind… dwelling on them, and believing them. They remember their first love. You do that, too, Luke seems to tell us.

What the Resurrection Means

This week has brought us a steady stream of reminders that life sometimes seems like nonsense. An airport attack in Brussels. Another one in Iraq. Yet another videotaped example of institutionalized racial profiling.

It would be easy to rush to the tombs of these innocent men and women and see only bewilderment and death.

Closer to home we have our own enigmatic interactions and happenings that push the limits of our capacity to hope in God.

But because of the resurrection, where our lives once looked like this…

…they now look like this:

Jesus’ defeat of death is real. The resurrection is far-reaching in its implications. Jesus’ rising from the dead calls us to a new way of living. Those women’s lives really started that day.

Because of Jesus’ resurrection, failure can become opportunity. Because of Jesus’ defeat of death, every ending has in it the seeds of a new beginning. Because of the presence in our lives of the resurrected Christ, where we have forgotten, we can again choose to remember. Because the stone was rolled away, our stony hearts can give way to compassion. Because Jesus did not remain among the realm of the dead, mourners can know that–if not now–then SOME DAY they will rejoice. Because of Christ’s victory over the grave, when others intend to keep us down, God can bring us back up again, rising with him.

That optimistic twin brother was right–where there’s manure, there’s got to be a pony somewhere. But not because we are optimistic people by nature. There are plenty of things to be pessimistic about, and with good reason. But the power of Christ’s resurrection opens us up to a new reality. It’s more than a new perspective on life. It’s new life altogether!

We can overcome evil with good. We can stare down death and know that it’s not the end. Even when we’re confronted with evil, we can be assured that the power of the rolled away stone is stronger than the power of the tomb. We can follow these wonderful women, and be first responders at scenes of tragedy, sharing the good news of God’s love in Christ.

If the resurrection of Jesus is real–if it transformed the world then–it is still transforming the world now. If Mary Magdalene and her friends could go from wailing tears to evangelistic zeal, there is hope for you in your despairing moments. If Jesus rose from the dead–and, friends, he did–he rises again out of the rubble of the world. Jesus even rises in our hearts, and empowers us to choose life with Him.

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

The Lord is risen indeed! Alleluia!

Alleluia! Christ is risen!

The Lord is risen indeed! Alleluia!