Tomorrow (Tuesday) I have the final exam in my class, Use of the Old Testament in the New. That can only mean one thing, and that is that it’s time for this:

Tag: Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Studies Carnival (November)

Bob MacDonald hosts this month’s Biblical Studies Carnival here. What, you thought blogs were so 2008? Well, they were. But they’re pretty 2012, too. Bob compiles a long list of blog posts in the field of Biblical Studies from the month of November.

I’m hosting the carnival next month, so if you know of good links I should include (anything that will be posted in December), please feel free to let me know.

Which Bible software program should I buy? Comparison of BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos

Which Bible software program should I buy? It’s an important question for the student of the Bible, especially if she or he is on a limited budget. Having now reviewed BibleWorks 9 (here), Accordance 10 (here) and Logos 4 (here) and now 5 (here), I want to compare the three programs and offer some suggestions for moving forward with Bible software.

There are some free programs available for download (E-Sword, for example), but my sense has been that if you want to have something in-depth, you’ll probably want to consider BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos.

If you’re in the market to buy Bible software, then, here’s how I recommend proceeding.

1. Think through why you want the Bible software.

I don’t mean in an existential sense; I mean: for what do you want to use Bible software? Personal Bible study? As a means to access electronic commentaries for sermon preparation? To do in-depth word studies in the original languages? To compare the Greek and the Hebrew texts of the Old Testament? For complex syntactical searches? To help generate graphics and handouts for a Sunday School class you teach? Some or all of the above?

Similarly, are there things you know you don’t need? Are you interested only in studying the Bible in English (or Spanish, or French…) but not necessarily in Greek and Hebrew? Are maps and graphics something you can easily access elsewhere? Is having a large library of electronic commentaries not a value?

I highlight these considerations because the answer to the question, “Which Bible software program should I buy?” is: It depends. It depends on why and for what you want Bible software. More on that below.

2. Explore BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos on their own merits.

Get a sense of what each can do by visiting their respective Websites (BibleWorks here, Accordance here, and Logos here). Look through those sites for videos which will let you see the programs in action. You can also look through the full reviews I’ve done of BibleWorks here, Accordance here, and Logos here (v.4) and here (just-released v. 5). In these reviews I look at multiple features and resources in each program.

BibleWorks is a PC program. You can run it on a Mac, though. This either requires a separate Windows license (= more $$), where it runs nicely in Parallels, etc., or you can use a “native” Mac version of it. The former option is costly and requires a lot of your Mac machine (though you get a fully-functinoing BibleWorks on a Mac that way). I can’t yet recommend the latter option, where it is in “Public Preview,” since the “native” Mac version looks only native to about two Mac operating systems ago… I expect BibleWorks will make improvements here, but I haven’t found BibleWorks on my Mac to be as functional as I’d like. It’s excellent on a PC, though.

Accordance is a Mac program. They have announced that they’ll introduce Accordance for Windows in 2013, and they have said that they are previewing that at SBL/AAR this week. (I understand that you can run Accordance on Windows now via an emulator, per the above link, but that it’s not 100% functional in the same way Accordance on Mac is.) Accordance is silky smooth–if I may call a Bible software program that. It is very Mac-like, which is a goal and priority of Accordance. Using it is truly enjoyable. Accordance also has an iOS app, which I haven’t used, as I do not own an iPhone, iPad, iOverbrain, etc. It looks like a stripped-down version of Accordance, but it’s free. If I had an iPhone, that would definitely be on there.

Logos works on PC and Macs. It’s also cloud-based, so that you can sync your work in Logos across computers, platforms, mobile devices, on the Internet using Biblia, and so on. Logos for the Mac feels fairly Mac-like, but not to the extent that Accordance does. However, being able to switch between a PC and a Mac in Logos and have everything sync via the cloud is a great feature. I noted in a Logos review recently how I was working in Logos 5 on a PC, then the next day opened Logos on my Mac to the exact same window I had just closed on a PC the day before.

3. Think about what your budget is.

You should actually probably do this before you check out the individual programs a whole lot–just to make sure you don’t end up spending money you don’t really have! Sometimes you’ll see a price tag associated with how much a base package would cost you if you bought all the resources in print. But this really doesn’t matter if you wouldn’t buy many of those resources in the first place (per point #1 above).

BibleWorks does not have packages, per se–it’s just the program and all its contents for $359. You can also purchase add-on modules in BibleWorks. Accordance has various collections (beginning with the basic Starter Collection at $49.99), which you can compare here. They sell various other products, as well. These base packages had been a little difficult to wade through and make sense of in Accordance 9, but the August release of Accordance 10 greatly simplified things. Logos also sells various base packages, starting at $294.95 retail price for their Starter package, and many other products. Note also that Accordance and Logos both offer discounts to academicians, ministers, etc.

4. Compare.

![]() Keep firmly in mind the purposes for which you want Bible software as you read the below. But I will offer some general insights.

Keep firmly in mind the purposes for which you want Bible software as you read the below. But I will offer some general insights.

Speed

BibleWorks (PC) and Accordance (Mac) take the cake here. I wrote here about the sluggishness of Logos 4 for searching. That’s improved somewhat in Logos 5. Where BibleWorks stands out is in its Use tab, new in BibleWorks 9. Via the Use tab, you can instantaneously see all the uses of a given word in an open version just by hovering over that word. I’m not aware of anything comparable in Accordance or Logos, and it’s a mind-blowing feature. Accordance, however, returns search results as quickly as BibleWorks, and starts up faster. I continue to be impressed with the speed of both BibleWorks and Accordance. I’m glad for the improvements in Logos, but hope they’ll continue to improve search speed.

Package for the Price

Had I written this post six months ago, the no-brainer answer would be that BibleWorks is best. For $359 you get everything listed here.

Comparable in Accordance is the Original Languages Collection for $299 (full contents compared here). This collection six months ago was not really comparable to BibleWorks, but with the release of Accordance 10, Accordance significantly improved on and expanded what’s available in its Original Languages Collection. Someone wanting Bible software for detailed original languages work could get a lot of what they need in Accordance for under $300. However, it remains true that you get more in BibleWorks that you have to pay extra for in Accordance (like the Center for NT Textual Studies apparatus and images, Philo, Josephus, Church Fathers, the Tov-Polak MT-LXX Parallel, etc.). That’s true compared with Logos, too.

Logos 5 is a little more difficult for me to size up here. In Logos 4 there was an Original Languages Library for $400 or so that was at least comparable to BibleWorks and Accordance (and included the 10-volume Theological Dictionary of the New Testament). Based just on package for the price, I still would have picked BibleWorks over Logos, but the release of Logos 5 has seen a restructuring of base packages that seems less than ideal for something like original language study. They do now have the Theological Lexicon of the OT and of the NT in the “Bronze” package, but the nearly $300 Logos Starter package doesn’t include the necessary and basic lexica for studying the Hebrew Bible, the Septuagint, and the Greek New Testament.

This is where what you want out of a Bible software program should dictate which way you go. Are you a seminarian with a primary interest in original language exegesis, with a preference for commentaries in print? If so, I recommend Accordance on Mac or BibleWorks on PC. Accordance also has good commentaries as add-ons (not much here for BibleWorks), but Logos has a large amount of digitized books, and tends on the balance (though not always) to run cheaper than Accordance for the same modules. (The cheapest BDAG/HALOT lexicon bundle is in BibleWorks.) But the larger library in Logos is perhaps at the expense of program speed, so you’ll want to weigh options here. If you preach weekly and don’t make much reference to Greek and Hebrew, wanting extensive commentaries instead, Logos could be the way to go for you.

Customizability and Usability

Here I favor Accordance of the three. BibleWorks is probably the least configurable. There are four columns in BibleWorks 9, but you can’t move things around much, whereas in Accordance and Logos you can put tabs/zones/resources more or less where you want them. Logos is plenty customizable, but the Workspaces feature in Accordance sets it apart from Logos. In Accordance you can save distinct Workspaces and have multiple ones open at a time. You can save “Layouts” in Logos, but from all I can see, you can only have one layout open at once. This has often slowed my study. You can detach tabs into separate windows with Logos, but for working on multiple projects at once (e.g., an NT use of the OT Workspace, an LXX Workspace, a Hebrew OT Workspace, an English Bible Study workspace, etc.), Accordance is tops.

For the record, both for my graduate studies and message preparation, Accordance is the first program I have open. Part of this is due to the fact that I prefer to use a Mac. (Within the last year I bought a cheap PC laptop just so I could keep using BibleWorks, which is still excellent.) But the multiple Workspaces option makes Accordance great for easy day-to-day use across multiple kinds of tasks. It’s been interesting to watch myself mouse over to the Accordance icon in my dock on my Mac before either Logos or BibleWorks.

Support

This is probably a toss-up. I’ve had positive interactions with everyone I’ve contacted in BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos. All have active and helpful user forums. All offer help files and how-to videos. (BibleWorks has the most extensive set of videos.) I was surprised to see how many how-to videos and manuals you could buy from Logos, but many of these have been produced by approved third-parties. I don’t think you should have to pay more money to learn how to use a program you already paid for.

Note-taking

One thing I haven’t extensively reviewed is the note-taking features, which are available in BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos. I particularly appreciate being able to highlight passages (which then stay highlighted every time I open that resource) in resources in both Accordance and Logos. Logos has an easier one-keystroke shortcut to highlight selected text, but there’s a delay in doing so; Accordance is faster here. But back when I was using only BibleWorks, I was concerned about saving notes in a file format that wouldn’t be accessible across computers and platforms, so all my notes were always just in Word or TextEdit (.rtf). I’ve continued this practice as I’ve begun using Accordance and Logos, so that any writing I generate is not confined within a given program.

In sum…

So, which Bible software program should you buy? It depends on why you want Bible software and the uses you’ll have for it. If you’re looking to build and access a large digital library, no one denies that Logos is the leader in that regard. It is also only Logos that connects to the cloud to sync across multiple devices. If you’re looking to really delve into the original languages, though, and do complex and fast searches, Accordance for Mac and BibleWorks for PC are preferable. (Logos 5 has offered significant improvement from Logos 4 in working closely with original language texts, but the search speed still needs to be improved.) BibleWorks gets you the most bang for your buck by including as many resources, versions, lexica, grammars, etc. as it does, but the interface and customizability of Accordance makes the latter more enjoyable and a little easier to use.

When it comes to the BibleWorks vs. Accordance vs. Logos question, I think at bottom each is a solid software program and good decision. You can’t go badly wrong with any of them. In fact, I now use all three on an almost daily basis. (Thanks again to each software company for the review copies.) But insofar as potential users may not want to have to purchase or learn how to use all three programs, I hope the above reflections are of use.

Next time…

I will post one more time in the near future along these same lines. In particular I plan to compare Septuagint study across BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos. I’ve covered this in each of my individual reviews already, but I’ll look at the Tov-Polak MT-LXX Parallel database in particular in each of the three, so you can see in more detail how each software program handles the same basic resource. In that post I will also write about more complex search features in BibleWorks, Accordance, and Logos, assessing how they compare.

(2015 UPDATE: That would-be blog post ended up as a published article in a journal of Septuagint studies. See more here.)

If you’ve made it this far (more than 2,000 words later), congratulations! Please feel free to leave me a comment or contact me if you are seriously considering Bible software and want to ask any questions about anything I’ve reviewed… or haven’t covered in my reviews.

January 2014 UPDATE: I have begun reviewing the Bible Study app from Olive Tree. You can see those reviews gathered here.

Biblical Studies Carnival (October) at BLT

Review of T. Muraoka’s Hebrew/Aramaic Index to the Septuagint

In studying the Septuagint, I’m regularly curious about how often the LXX translators used the same Greek word to translate a given Hebrew word. How often, for example, does καρδία translate the Hebrew לבב? And what other Greek words are used to translate it? Similarly, I wonder, for occurences in the Greek text of καρδία, what other Hebrew words might it be translating?

Takamitsu Muraoka has made such questions an emphasis of his scholarly writing and publishing throughout his career. His Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint is one of the standard lexicons in the field, and his Greek-Hebrew/Aramaic Two-way Index to the Septuagint is the best thing I’ve seen in print for Hebrew-Greek lexical studies in the Septuagint.

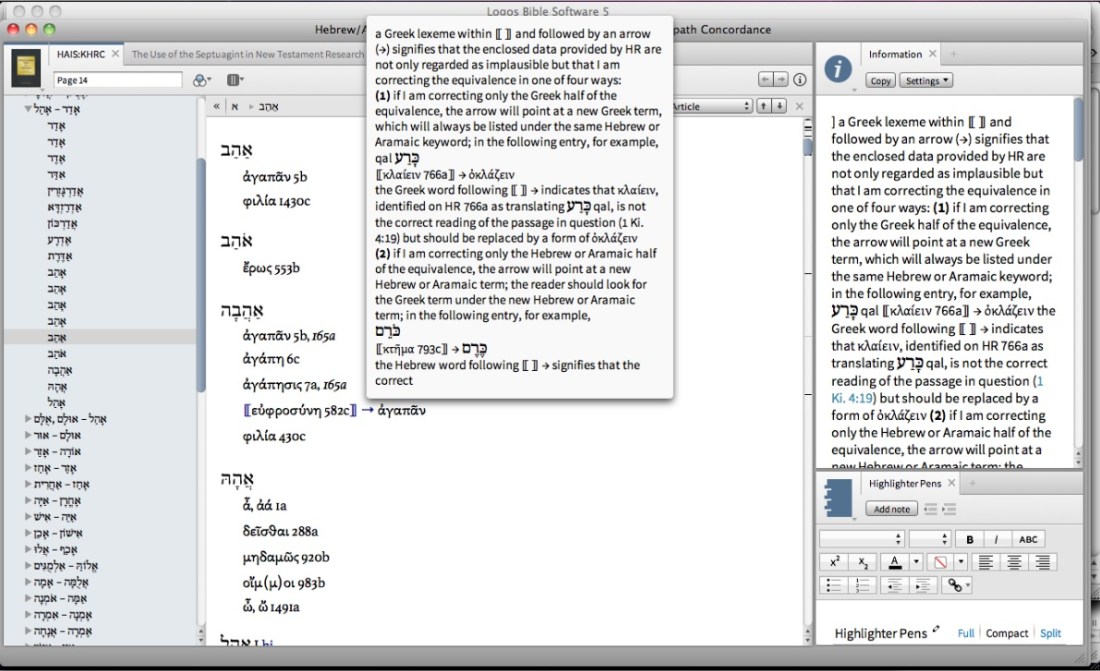

Preceding that latter work was Muraoka’s Hebrew/Aramaic Index to the Septuagint: Keyed to the Hatch-Redpath Concordance. I’ve had a chance to use the work in Logos Bible software; this post contains my review.

Muraoka notes the impetus for the work in the Introduction. The Hatch-Redpath Concordance (hereafter HR), published around the turn of the 20th century, listed all Greek words used in the Septuagint with the Hebrew they were thought to have translated. At the back of the concordance was a list that basically noted the reverse, showing Hebrew words alphabetically with the Greek words used to translate them… or, rather, a key to the Greek words in question. As Muraoka notes, you would have this entry in HR:

אָמַר qal 37 c, 74 a, 109 c, 113 c, 120 a, 133 a, 222 a, 267 a, 299 b, 306 b, 313 a, 329 c, 339 b, 365 a, 384 a, 460 c, 477 a, 503 c, 505 c, 520 b, 534 c, 537 b, 538 b, 553 b, 628 b, 757 b, 841 c, 863 c, 881 c, 991 b, 1056 b, 1060 a, 1061 a, 1139 a, 1213 b, 1220 c, 1231 b, c, 1310 b, 1318 b, 1423 c, 1425 b, 69 b, 72 b, 173 a, 183 b, c, 200 a (2), 207 c, 211 b.

Whereas the Greek to Hebrew portion of HR lists the Hebrew words underlying the Greek of the LXX, the Hebrew to Greek portion at the back just has page and column reference numbers, as above. So the user of HR would have to turn to page 37, column c, page 74, column a, etc., etc., in order to see what Greek words were in those locations. Only in that tedious way could the user of HR see all the Greek words used to translate the Hebrew אָמַר.

Muraoka’s wife (who is a true co-author of this work) tediously wrote out (yes, by hand) each Hebrew to Greek entry so that instead of page and column numbers, it contained actual Greek words. The above, then, would look more like this:

אָמַר qal αἰτεῖν (37c), ἀναγγέλλειν (74a)…

…and so on. The HR page and column numbers are retained, but now the user doesn’t have to flip back and forth, since the Greek words are all in one place.

T. Muraoka then took his wife’s data and critically examined HR’s assessments in as many places as he could, drawing on advances in the past century in textual criticism, manuscript availability (like the Dead Sea Scrolls), and adding in analysis of “apocryphal” books, which HR had not fully included. The resulting revision updates both HR’s work and his wife’s manual collation.

What results, then, is an eminently helpful work where one can look up any Hebrew word and see all the Greek words used to translate it across the Septuagint. To be able to do this is valuable, and Muraoka makes it easy.

There are two things that lack here, though neither one of them is really the goal of the work, so I don’t actually criticize it for these omissions. First, there are not frequency numbers. It could be especially helpful to know not only what Greek words translate a given Hebrew word, but how many times each does, so that the user can get a sense of the distribution of each. Muraoka doesn’t have this. Second, he doesn’t have glosses or translation equivalents for words, so there is no English in this index.

But this is an index, and marked as one, so neither of those is a flaw in Muraoka’s book. In fact, here is where using Muraoka in Logos is especially helpful: you can tie tabs together so that a simple click from Greek or Hebrew in his index takes you to a corresponding Greek or Hebrew lexicon in Logos, where you can see that word’s meaning. Logos in this way really enhances Muraoka’s tool. And, of course, frequency statistics are easy to come by in Logos.

This is a good resource, and worth owning for students and professors of the Septuagint. A question remains: with all that Logos can already do, is it superfluous to purchase Muraoka’s index? Using the Bible Word Study feature in Logos, for example, I can see all of the Hebrew words that a given Greek word is used to translate, as well as all of the Greek words used to translate a given Hebrew word, as here (click to enlarge):

This may be sufficient for what many people need, especially since you can also search for a Hebrew lemma from within the Greek Septuagint text in Logos and receive results in Greek, so that you have before you all the verses with all the various Greek words that translate that Hebrew lemma. (I just learned this today from the user forums-very cool.)

But if you’ve got the money (especially if you qualify for an academic discount), and are sitting on the fence about Muraoka’s resource, I recommend it. It’s nice to have easily at hand a listing of all Greek words used to translate a Hebrew word in the Septuagint, even if there are other ways to get that information in Logos. Here it’s consolidated.

One other nice feature is that all the abbreviations throughout the index are hyperlinked to what they stand for, which you can bring up just by mousing over them:

You can see there are no verse references given, which are useful for in-depth study of Greek translations. Muraoka’s more thorough Greek-Hebrew/Aramaic Two-way Index to the Septuagint offers more depth in this regard than this 1998 Hebrew/Aramaic (one-way) index. No Bible software currently offers the two-way index, but it would be great if Logos were able to make it available in the future.

All in all Muraoka’s Hebrew/Aramaic Index to the Septuagint is a solid resource. And its digitization in Logos has been well done, too. Logos can already accomplish much of what’s in this index, but the one serious about the Septuagint may want to have any and all tools at her or his disposal. In that case, this is a worthy addition to one’s library.

Thanks to Logos for the free review copy of this work, offered without any expectation as to the positive or critical nature of my review. Muraoka’s Hebrew/Aramaic Index to the Septuagint is available in Logos here.

Logos 5 Review: Further Impressions

Last week I posted some initial impressions of the just-released Logos 5. Having had a little more time with it now, here are some further impressions I have.

The Data Sets guide the user through resources nicely and can do some unique things.

The Logos 5 Data Sets are what most stand out to me on further use. Two in particular to note:

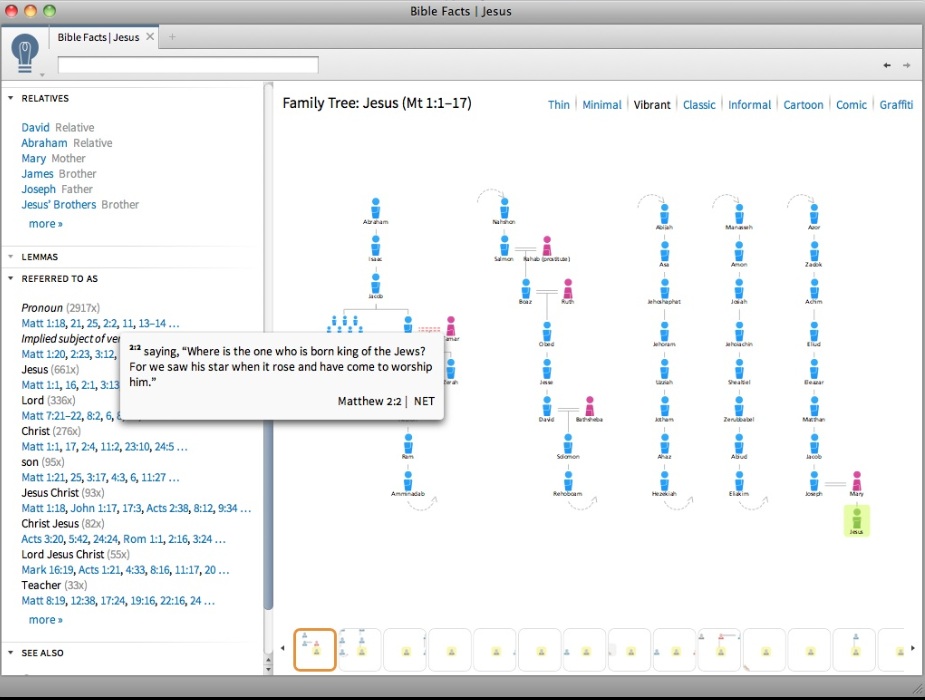

Bible Facts (People): this allows me to search by a referent and not just by the actual wording in the text. For example, by going to “Tools” from the home screen, then “Bible Facts,” I can type in “Jesus” to see not just where that word occurs in the text, but also where the text is referring to Jesus, whether by “he,” as “Christ,” “Son,” and so on. It’s a lovely and very impressive feature. Take a look, and click on the image to see larger:

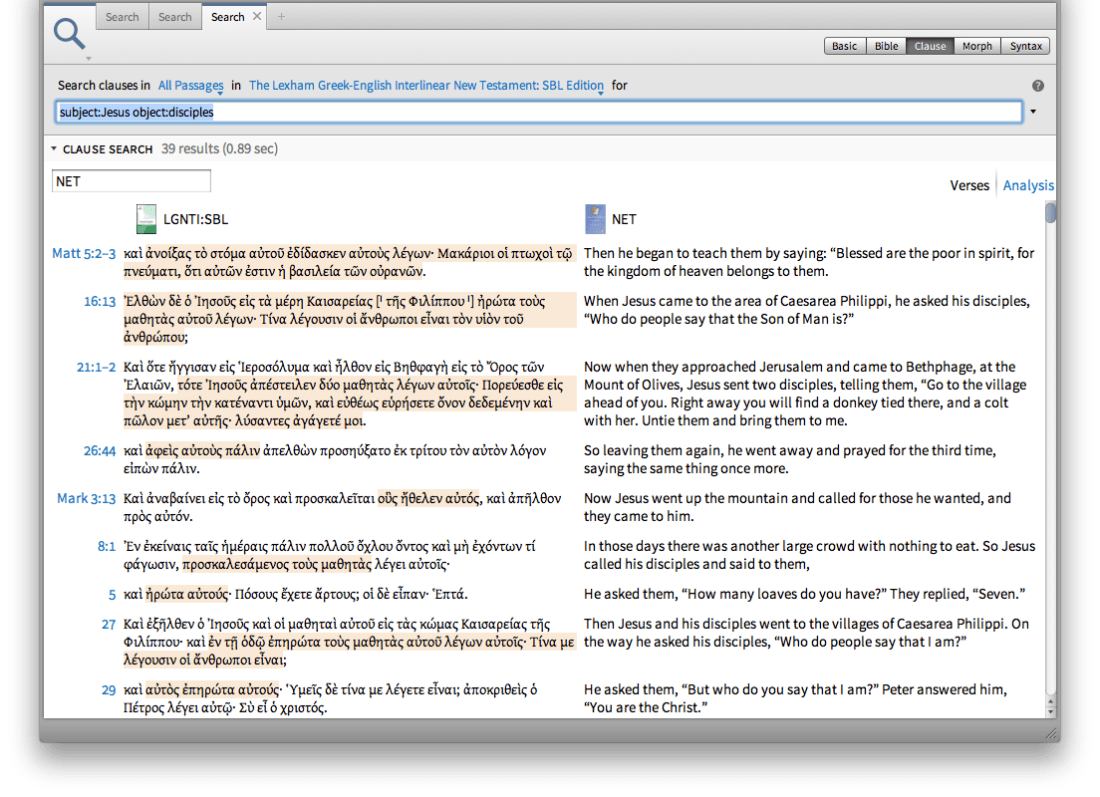

Clause Search: Another you-have-to-use-it-to-believe-it feature. Here I can find (in less than a second) every time Paul is the subject of a clause, whether “Paul” occurs in the text or not. This means I can search on Paul in Acts, but also on the things Paul says about himself (using just “I” in the text) in his epistles. Or, I can search at the clause level for times when Jesus is the subject and his disciples are the object. As here:

Note that the first result is Matthew 5:2-3, where the words “Jesus” and “disciples” don’t even appear in the text (!) but the “he” refers to “Jesus” and “them” to his disciples. Of course, there is some interpretation at play here in the results. The disciples are the closest referent to “them” in the text, but Matthew 5:1 also mentions the crowds, who could also be what “them” refers back to. But the fact that the Clause Search can, in under a second, return these kinds of results is astounding. It’s searches like this that are why Logos markets itself as “powerful.”

The search speed of the program has improved (though is still not the fastest on the market).

Logos 5 is an overall faster program than Logos 4. (I use Logos primarily on a Mac.) The clause searches I’ve done, for example, have been lightning fast. But Logos is still not quite as fast at returning results for original language word searches as BibleWorks or Accordance. I wondered with Logos 4 whether this might be because Logos has a large library of resources. Whatever the reason, the multi-second waits for search results to come up are less common in 5 than in 4. Most of my searches have been showing results in a second or less, even the clause searches that I’d expect to take longer. Accordance and BibleWorks, however, give near instantaneous search results. Logos, with v. 5, is at last in the same ballpark with regard to speed.

The contents of the base packages have changed significantly.

This does not affect previous Logos users necessarily, in that you always keep your Logos resources with you (for life). So if you upgrade to Logos 5 via a new base package, anything you had bought previously stays with you, even if it’s not in the new base package. For someone like me who primarily uses Bible software to study biblical languages, the Original Languages Library in Logos 4 was great (except, perhaps, for its lack of an English translation of the Septuagint). Even with its retail price under $500, that package still included the full 10-volume Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT), making it a good deal, and a great deal with the academic discount.

Now to have TDNT in a base package (if you don’t already own it), you have to buy the “Gold” package at a retail price of just over $1,500. The Silver package in Logos 5, that I received to review, includes the entire New American Commentary set, the full Pulpit Commentary set, the Lexham Analytical Lexicon to the Septuagint (and the same to the Greek NT), several Greek and English Apostolic Fathers texts, the Theological Lexicon of the OT (and that of the NT), as well as many more resources for a retail price of about $1,000. I was particularly excited to see a new English translation of the Septuagint, coming from the Lexham suite by Logos. Users will simply have to weigh whether the included resources in a package justify its cost. The Silver package seems to be worth the price. (Though note that the fairly standard Rahlfs Septuagint text is not included in Silver; Swete’s text is.)

This video from Logos gives a good overview of what’s new in Logos 5, with special focus on the Data Sets:

See also my initial impressions of Logos 5 in an earlier review.

Thanks to Logos for the review copy of Logos 5 with the Silver package, provided to me simply with the expectation that I offer my honest impressions of the program.

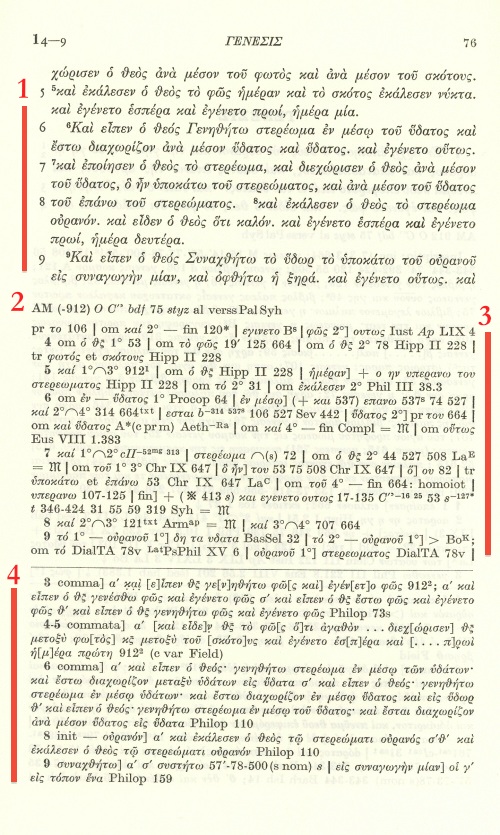

How to Read and Understand the Göttingen Septuagint: A Short Primer, part 1

The Göttingen Septuagint is the Cadillac of Septuagint editions. It’s the largest scholarly edition of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Its full name is Septuaginta: Vetus Testamentum Graecum Auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum, published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen, Germany. The Göttingen Septuagint has published more than 20 volumes spanning some 40 biblical books (counting the minor prophets as 12), and publication of additional volumes is in progress.

But the Göttingen Septuagint is not for the faint of heart, or for the reader who is unwilling to put some serious work in to understanding the layout and import of the edition and its critical apparatuses. A challenge to using Göttingen is the paucity of material available about the project, even in books about the Septuagint. An additional challenge is that the critical apparatuses contain Greek, abbreviated Greek, and abbreviated Latin. The introductions to each volume are in German, though below I cite from English translations of the introductions to the volumes of the Pentateuch.

It is my intention with this post, and a second to follow, to give a short primer or user’s guide to the Göttingen edition. Here I offer suggestions on how to read and understand the text, the apparatuses, the sigla/abbreviations, the introductions, and point to additional resources that will be of benefit to the Göttingen user.

I recently put together a basic orientation to the scholarly editions of the Hebrew Bible and the Greek translation of the same. That is here. It is worth noting again that the International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies (IOSCS) has a good, succinct article on the various editions of the Septuagint. Below, “OG” stands for “Old Greek.” They write:

The creation and propagation of a critical text of the LXX/OG has been a basic concern in modern scholarship. The two great text editions begun in the early 20th century are the Cambridge Septuagint and the Göttingen Septuagint, each with a “minor edition” (editio minor) and a “major edition” (editio maior). For Cambridge this means respectively H. B. Swete, The Old Testament in Greek (1909-1922) and the so-called “Larger Cambridge Septuagint” by A. E. Brooke, N. McLean, (and H. St. John Thackeray) (1906-). For Göttingen it denotes respectively Alfred Rahlfs’s Handausgabe (1935) and the “Larger Göttingen Septuagint” (1931-). Though Rahlfs (editio minor) can be called a semi-critical edition, the Göttingen Septuaginta (editio maior) presents a fully critical text….

In other words, rather than using a text based on an actual manuscript (as BHS, based on the Leningrad Codex, does), Göttingen utilizes a reconstructed text informed by a thorough examination of manuscript evidence. Göttingen has two critical apparatuses at the bottom of the page of most volumes. Because it is an editio maior and not an editio minor like Rahlfs, a given print page can have just a few lines of actual biblical text, with the rest being taken up by the apparatuses. Here’s a sample page from Genesis 1. Note the #s 1-4 that I’ve added to highlight the different parts of a page. Below I explain #1 and #2; the rest comes in a follow up post.

1. The reconstructed Greek critical text (“Der kritische Text”)

With verse references in both the margin and in the body of the text, the top portion of each page of the Göttingen Septuagint is the editorially reconstructed text of each biblical book. In the page from Genesis 1 above, you’ll notice that the text includes punctuation, accents, and breathing marks.

Like the NA27 (and now NA28) and UBS4 versions of the Greek New Testament, Göttingen is a critical or “eclectic” edition, which “may be described as a collection of the oldest recoverable texts, carefully restored book by book (or section by section), aiming at achieving the closest approximation to the original translations (from Hebrew or Aramaic) or compositions (in Greek), systematically reconstructed from the widest array of relevant textual data (including controlled conjecture)” (IOSCS, “Critical Editions”).

Of the critical text, John William Wevers, in his introduction to Genesis in Göttingen, writes:

Since it must be presupposed that this text will be standard for a long time, the stance taken by the editor over against the critical text was intentionally conservative. In general conjectures were avoided, even though it might be expected that future recognition would possibly confirm such conjectures.

It must be clearly evident that the critical text here offered labored under certain limitations. The mss, versions and patristic witnesses which are available to us bring us with few and small exceptions no further back than the second century of our era. Although we do know on the basis of second and third century B.C.E. papyri something about the character of every day Greek used, our knowledge of contemporary literary Greek is very limited indeed. In other words, the critical text here offered is an approximation of the original LXX text, hopefully the best which could be reconstructed on the basis of the present level of our knowledge. The editor entertains no illusion that he has restored throughout the original text of the LXX.

One cannot simply say, “The LXX says…,” because then inevitably an appropriate response is, “Which LXX? Which manuscript? Which or whose best attempt at reconstruction?” So “approximation of the original” and “hopefully the best which could be reconstructed” are key phrases here.

All the same, especially in the newer Göttingen editions, the volume editors have viewed and listed the readings of many manuscripts and versions. The critical apparatuses are where they list those readings, so the user of Göttingen can see other readings as they compare with the critically reconstructed text. (Because the Göttingen editions are critical/eclectic texts, no single manuscript will match the text of the Göttingen Septuagint.) And although scholarly editions of the Greek New Testament also present an eclectic text, neither the NA27 nor UBS 4 is an editio maior, as Göttingen is. (The Editio Critica Maior is just recently begun for the GNT.) Serious works in Septuagint studies, then, most often use the Göttingen text, where available, as a base.

2. The Source List (“Kopfleiste”)

Not every volume has this feature, but the five Pentateuch volumes, Ruth, Esther, and others do. The Kopfleiste comes just below the text and above the apparatuses. Wevers notes it as a list of all manuscripts and versions used, listed in the order that they appear in the apparatus on that page. A fragmentary textual witness is enclosed in parenthesis.

In the above Kopfleiste, the parentheses around 912 mean that papyrus 912 is fragmentary. The “-” preceding it, Wevers notes, means that its text ends on the page in question. So although this particular Göttingen page has Genesis 1:4-9 reconstructed in the critical text (“Der kritische Text”), “(-912)” in the Kopfleiste indicates that the fragmentary papyrus 912 does not actually contain text for all the verses on the page. Looking up papyrus 912 in Wevers’s introduction to Genesis, in fact, confirms that this third to fourth century papyrus contains only Genesis 1:1-5.

By contrast, the “(D-)” here

indicates that the uncial manuscript D has its text beginning on the page in which it appears in Göttingen. The above shot is from the Göttingen page containing Genesis 1:9-13. The first time D has anything to offer (since it is fragmentary, indicated by its enclosure in parentheses) is at 1:13. This alerts the reader that D has no witness to Genesis 1:1-12. Wevers’s introduction then gives more information about the contents of that manuscript. So, too, with the minuscule manuscript 128 above–the introduction says of 128, “Init [=Latin initium=the beginning] – 1,10 is absent.”

Wevers adds:

Should a piece of text be lacking due to some external circumstance in a particular ms, this is noted in the Source-List. For example if ms 17 lacks the text this is shown as O-17. What this means is that the entire O except 17 (which belongs to O) has the text in question. The abbreviation al (for alia manuscripta) refers to the mss which belong to no particular group, i.e. the so-called codices mixti as well as mss which are too fragmentary to allow classification. The expression verss designates all the versions which have the complete text of Genesis. Versions such as Syh to (31,53) and Pal, whose texts are not complete, are listed at the end of the Source-List (Kopfleiste).

In terms of the order of citing Greek textual witnesses:

In the apparatus the citation of Greek sources appears in the following order: First place is occupied by the uncial texts in alphabetical order, and characterized by a capital letter. Then the papyri are cited in the order of 801 to 999. Then the hexaplaric group [AKJ: “O” above] is given as well as the Catena groups [AKJ: C‘’], with the mss groups following in order as: b d f n s t y z; then the codd mixti, followed by the mss without a Rahlfs number. Next come the NT citations, and finally, the rest of the patristic witnesses in alphabetic order.

In the next part of this Göttingen Septuagint primer, I’ll explore #3 and #4 above, the First Critical Apparatus (“Apparat I”) and the Second Critical Apparatus (“Apparat II”), as well as take a closer look at the contents of the Introductions in the Göttingen editions (“Die Einleitung”).

UPDATE: Part 2 of the primer is here, with still more to follow.

Thanks to Brian Davidson of LXXI for his helpful suggestions on an earlier draft of this post.

Katharine Bushnell (1856-1946): “God does not curse women because of Eve”

Two days after All Saints Day, I express my admiration now for a perhaps even lesser-known “saint” than Perpetua, Moses the Black, or John Huss.

Katharine Bushnell lived from 1856 to 1946. She was a doctor, a missionary, an advocate for those without other advocates, and a theologian. Her commitment to the authority of Scripture was strong. About the Bible she said, “No other basis of procedure is available for us.” She learned Greek and Hebrew, and was particularly interested in applying her knowledge of biblical languages to understanding what the Bible had to say about gender. She spoke seven languages.

Author and theologian Mimi Haddad (where I first learned about Bushnell, via this PDF article) writes about her:

Bushnell grounds the ontological equality of men and women first in the early chapters of Genesis where, according to Bushnell, we learn that Adam and Eve were both created in the image of God, that Adam and Eve were both equally called to be frutiful and to exercise dominion in Eden, that Eve was not the source of sin, and that God does not curse women because of Eve.

Bushnell began a hospital of pediatrics in Shanghai, was part of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and helped found a homeless shelter for women in Chicago.

Psalm 68:11 says, “The Lord announces the word, and the women who proclaim it are a mighty throng.”

Bushnell joins Perpetua and countless others as part of a mighty throng of women who have proclaimed God’s word in ways that continue to inspire today.

What’s new in Logos 5

This video from Logos shows what’s new in Logos 5. It mentions some of the same features I wrote about in my early review. Of special note, though, is the explanation of the Bible Sense Lexicon, new in Logos 5, beginning at 2:23. The Silver package I received for review does not have the Bible Sense Lexicon, but the Gold package and packages above Gold do have it.

More Logos-created videos introducing version 5 are here.

Thanks to Logos for the review copy of Logos 5 with the Silver package, provided to me simply with the expectation that I offer my honest impressions of the program, which I began here.

Logos 5 Review: Initial Impressions

Logos 5 has arrived.

I started using Logos 4 two months ago for a review I finished last week. Now version 5 is released today. But 4 had been out several years, so v. 5 has been in the works for some time. Having had and used Logos 5 for a few days now, I want to offer an initial set of impressions by way of review.

As I installed Logos 5, it was nice to know that I’d have access to all of my same resources, layouts, and highlights in books from Logos 4 when version 5 downloaded. This is one of my favorite things about Logos, and a feature that sets it apart from other Bible software. Logos works best with Internet enabled; you use a log-in that works across multiple computers and devices. After using Logos on a Mac, yesterday I opened it on my PC, and it opened exactly as I had left it on the Mac–all the same windows opened to all the same pages, like I had never stopped working. This is an immense time saver and a great feature.

Knowing this made the thought of installing 5 in place of 4 easier to deal with. And, sure enough, when I opened Logos 5, even though I had a new Logos engine, all was as I had left it the last time I had used 4. The installation itself took 2.5 hours (on a machine with no Logos 4 on it at the time), with a long indexing process of some 5 hours or more to follow.

The icon in my dock for Logos 5 is the same as Logos 4 (unless this is still to be updated?)–I would have expected a change here to set apart the new product even more.

Logos has also changed the structuring of their base packages, so that I am reviewing something called “Silver,” a new combination of resources. There are, in fact, seven new base packages in Logos, as noted in their table below. The sale price is offered in conjunction with the new release.

| Full Title | Resource Count | Print List Prices | Retail | Sale (15% off) | |

| 1 | Starter | 207 | $3,500 | $294.95 | $250.71 |

| 2 | Bronze | 426 | $8,000 | $629.95 | $535.46 |

| 3 | Silver | 699 | $13,000 | $999.95 | $849.96 |

| 4 | Gold | 1,037 | $21,000 | $1,549.95 | $1,317.46 |

| 5 | Platinum | 1,327 | $28,700 | $2,149.95 | $1,827.46 |

| 6 | Diamond | 1,993 | $52,500 | $3,449.95 | $2,932.46 |

| 7 | Portfolio | 2,563 | $78,000 | $4,979.95 | $4,232.96 |

The Silver package is certainly an upgrade from the Original Languages Library I reviewed in Logos 4. The Silver package includes Swete’s Cambridge Septuagint, the entire New American Commentary series, a ton of preaching/illustration resources, and more. My library expanded significantly upon downloading Silver.

The default font changed (across resources) to a font I found less readable. It took me all of 30 seconds, though, to figure out how to go into preferences and change it back to a font called “Default (Logos 4).”

What’s new in Logos 5? The two most obvious changes are visible below (click image for larger). For one, the icons and command bar at top are joined by three additions: “Documents,” “Guides,” and “Tools.” This gives the user quicker access to more features and tasks in Logos.

The second big noticeable change is the addition of more “Guides” (it becomes obvious why it has its own place right next to the command bar). Note above the “Topic Guide,” Bibliography, and “Sermon Starter Guide.” (These join the Exegetical and Passage Guides.) The Bibliography is especially helpful to this occasional writer of academic papers, and can be adjusted to various styles.

Note also a neat customizable reading plan guide (below at bottom right, how I could read the Septuagint in a year) and a “Bible Word Study” (at top right) with graphic, among other results that come up.

I have mixed feelings about the additions of new Guides in Logos. Though my initial skepticism about the Exegetical and Passage Guides changed to appreciation the more I used them in Logos 4, it’s hard to know at this early stage of using Logos 5 whether these guides will prove helpful or just seem like clutter. The Sermon Guide holds promise, as it gathers resources in one place that would take time to compile by hand. However, the Exegetical and Passage Guides already do this, albeit with a slightly different focus.

The Bible Facts feature (new in Logos 5) is pretty cool, and could be useful in teaching settings. See here:

Whoever does graphic design at Logos is aces. Follow them on Facebook and you’ll see well-done graphics for verses each day. Bible Facts incorporates that. This is a good addition in Logos. It auto-suggests search terms and returns results quickly.

More about Logos 5, including full details of what’s new, can be found here, with some brand new videos here. I’ll provide an additional review installment once I’ve had chance to spend more time with the program.

UPDATE: A bit more from me on Logos 5 here.

UPDATE 2: A week later, further impressions on Logos 5.

Thanks to Logos for the review copy of Logos 5 with the Silver package, provided to me simply with the expectation that I offer my honest impressions of the program.