Isaiah 53 is one of the clearest prophecies of Jesus the Messiah in the Hebrew Scriptures. This chapter has changed the lives of thousands of people–both Jews and Gentiles–who have read the text and believed in the One who fulfilled these prophecies in glorious detail.

Thus begins Mitch Glaser’s Introduction in The Gospel According to Isaiah 53: Encountering the Suffering Servant in Jewish and Christian Theology (affiliate link). In three parts the book expounds how the prophecies of Isaiah 53 relate to and are ultimately fulfilled in the person of Jesus. (The full passage the book treats is Isaiah 52:13-Isaiah 53.)

The first section, a sort of exegetical prelude, discusses “Christian interpretations” and “Jewish interpretations” of Isaiah 53. The second section is a biblical theology of Isaiah 53 (with particular attention to its use throughout Scripture). The third and concluding section speaks to “Isaiah 53 and Practical Theology,” with an emphasis on how to preach the passage, both from the pulpit and in conversation.

The book is “designed to enable pastors and lay leaders to deepen their understanding of Isaiah 53 and to better equip the saints for ministry among the Jewish people.”

The first thing I noticed about the book is that it’s just as much an apologetic for Jesus-as-suffering-servant as it is an academic study of Isaiah 53. It’s not that it lacks academic substance, though. This is a meaty book, and pleasingly so.

Regarding the book’s explicitly evangelistic intent–there may be some who are uncomfortable with the description of Chosen People Ministries’ “Isaiah 53 Campaign” (including 75,000 postcards to Jewish homes and 40,000 voice blasts=robo-calls?). I’ll admit that I question the potential efficacy of pre-recorded phone messages for reaching anyone with the Gospel (though God can use anything!). But see blogger Joel Watts for his helpful (refreshing!) take on the blending of the academic and evangelistic enterprises, especially in the context of this book.

You can find a full list of contributors in the table of contents here (pdf). A few names to highlight are Walter C. Kaiser Jr., Darrell L. Bock (one of the co-editors), Craig A. Evans, and Donald R. Sunukjian. I particularly appreciated the book’s treatment of the New Testament use of Isaiah 53. The chapter by Michael J. Wilkins lists the quotations of Isaiah 53 in the NT and additional allusions to it in the Gospels. (He makes a key point, that Jesus himself understood “his mission and death in the light of Isaiah 53.”) Darrell Bock goes in depth with a comparison of the Greek and Hebrew texts of Isaiah 53:7-8, highlighting its use in Acts 8 where Philip explains the passage to the Ethiopian eunuch.

Something to critique in this book is that there were a few generalizations of Jews that I found to be unfair, particularly in the chapter “Using Isaiah 53 in Jewish Evangelism.” Mitch Glaser writes:

I think I can safely say that, in the United States, most Jewish people would recognize Isaiah as the first name of a professional athlete sooner than they would recognize the prophet of biblical literature.

Granted, he is operating from the assumption that “most Jewish people are not Lubavitch, Hasidic, or Orthodox,” but still…. What was more surprising to me: “Most Jewish people do not understand or believe in biblical prophecy” and, “Most Jewish people do not believe in sin.” Glaser does (only later) qualify these with, “We must note that all of the above does not apply to those who hold to traditional Jewish theological positions,” but he would have been better off saying something like “many secular or ethnic but non-religious Jews…” or at least supporting his statements with statistics from surveys rather than anecdotal evidence. Glaser himself is a converted Jew who has a compelling conversion story, but I still found those characterizations to be frustrating. I wonder how helpful such statements could be in advancing an evangelistic cause in conversation with another Jew.

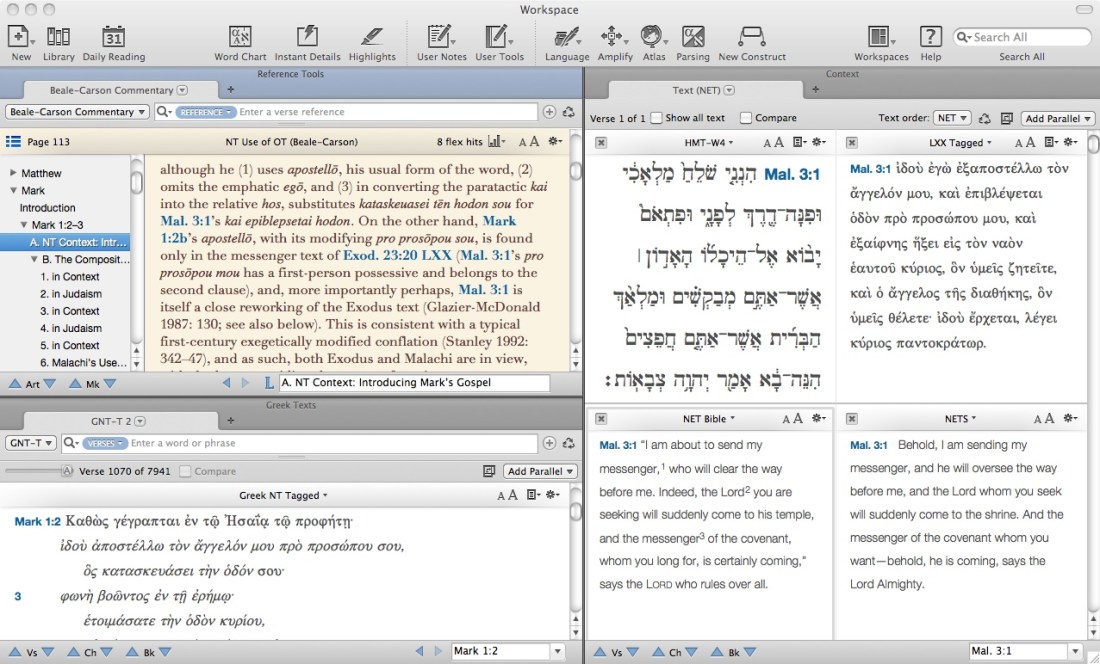

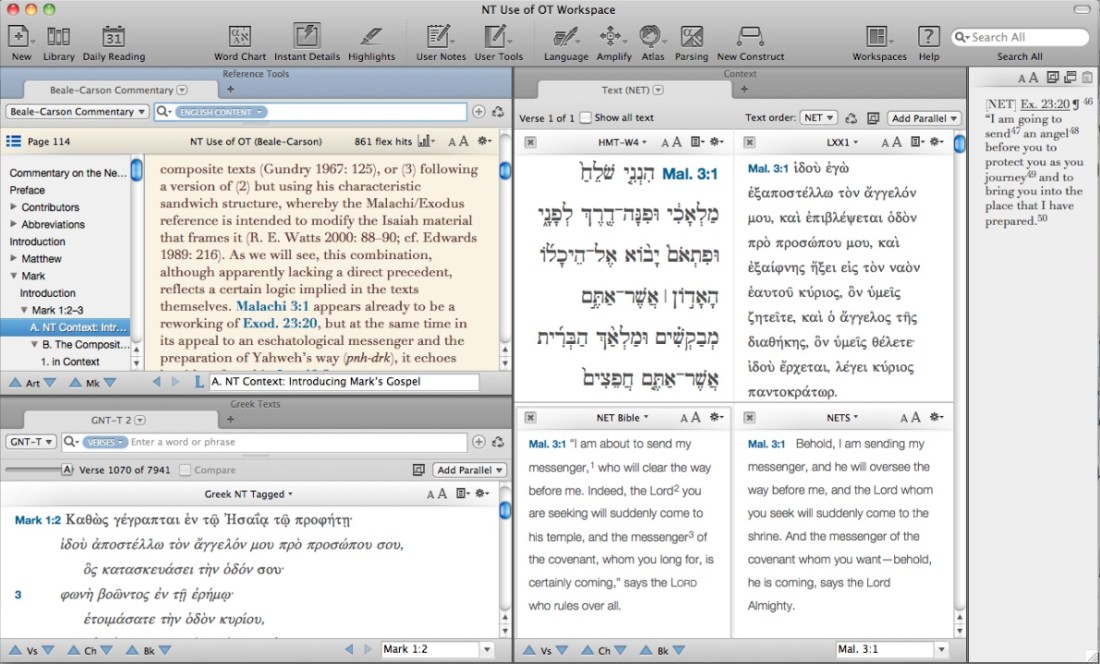

This next thing to highlight may seem a small point to some, but as someone seeking to keep my Hebrew and Greek going, I appreciated the actual Hebrew and Greek fonts throughout the book (i.e., not just transliteration), which are clear and easy to read. I did think, however, about an intended audience of “pastors and lay leaders” who may have desired transliteration, too. (All Hebrew and Greek is translated into English.)

Darrell Bock’s conclusion summarizes all the essays of the book, with key quotations. Having this there was a big help in piecing everything together again. The Gospel According to Isaiah 53 will not be far from my reach in coming months and years. I expect I will often reference this compendium of biblical scholarship on a vital text. My hesitations about the characterizations of Jews above notwithstanding, there is a good deal here that can be useful for Christian-Jewish conversations about the Suffering Servant.

I received a free copy of The Gospel According to Isaiah 53 with the only expectations of providing an (unbiased and honest) review on this blog. Its publisher’s product page is here. It’s on Amazon here (affiliate link).