Alas, the burden and the glory of preaching consist in proclaiming things that are not yet fully realized, but the hope for them holds a powerful grip upon the faithful imagination.

–Feasting on the Word

Here is a 12-volume commentary set that covers all the lectionary readings from multiple angles. Feasting on the Word offers four different “perspectives” (theological, pastoral, exegetical, and homiletical) for each lectionary passage in the weekly Revised Common Lectionary.

The 12 volumes cover the three-year lectionary cycle (A, B, and C), split into four volumes per year:

- Advent through Transfiguration

- Lent through Eastertide

- Pentecost and Season after Pentecost 1 (Propers 3-16)

- Season after Pentecost 2 (Propers 17—Reign of Christ)

The Scripture index makes it accessible to preachers who are not following the lectionary, too. From the Logos product page:

The editors and contributors to this series are world-class scholars, pastors, and writers representing a variety of denominations and traditions. And while the twelve volumes of the series will follow the pattern of the Revised Common Lectionary, each volume will contain an index of biblical passages so that non-lectionary preachers, as well as teachers and students, may make use of its contents.

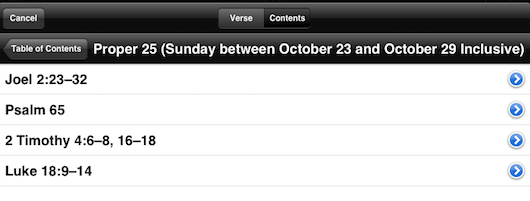

Logos Bible Software has the full set in a format that is hyperlinked, laid out well, and easy to navigate by date or Scripture reference. Here’s the Table of Contents in the Logos iOS app for the current volume:

Here’s how a given Sunday looks:

And then each of the passages splits into the four “perspective” sections.

Since being able to access Feasting on the Word, it’s actually jumped toward the beginning of my pile (or bytes) of resources that I consult when preaching. I try to pray through my preaching ideas from the text and in conversation with others before consulting commentaries, but the “Homiletical Perspective” (and the other sections, for that matter) do a good job of helping the preacher think about how to preach a text.

The Theological Perspective and Exegetical Perspective might be the best starting points in this commentary. Perhaps by design and due to the constraints of this resource, they are not as in-depth as you would find with a commentary on a given book of the Bible. But those two sections do show a general awareness of the major interpretive issues a preacher needs to be aware of.

The Pastoral Perspective differs from the Homiletical Perspective in that the former helps the preacher be aware of pitfalls and opportunities in preaching a text. For example, Stacey Simpson Duke offers the following pastoral suggestion on Isaiah 11:1-10 (which is the OT text for the 2nd Sunday of Advent in a couple of weeks):

Our fear for children’s safety and future is especially acute. Some in our congregations may have had the tragic experience of a child’s death; they may be particularly fragile when it comes to Isaiah’s images of vulnerable children living and playing in safety. That grief may not be confined to those who have suffered the loss of near ones. We are intimately acquainted with suffering children through heartbreaking images broadcast via the electronic media. This produces its own brand of grief. Isaiah’s word is for all, but the pastor must be sensitive to the grief in the room. Isaiah promises future security; how might this be a word of hope for those from whom security has already been stolen? Answers are not easy, but the pastor who wants to care for congregants in grief will want to wrestle with the question.

This has been the section of the commentary that I most consult.

I appreciate the overall depth and thoughtfulness of the series. This portion from the series introduction is apropos:

We also recognize that this new series appears in a post-9/11, post-Katrina world. For this reason, we provide no shortcuts for those committed to the proclamation of God’s Word. Among preachers, there are books known as “Monday books” because they need to be read thoughtfully at least a week ahead of time. There are also “Saturday books,” so called because they supply sermon ideas on short notice. The books in this series are not Saturday books. Our aim is to help preachers go deeper, not faster, in a world that is in need of saving words.

So far, I not only can recommend Feasting on the Word, but have begun drawing on it as a regular part of my preaching preparation each week. I’ll write more about the series in a future post.

Thanks to Logos Bible Software for the review copy of Feasting on the Word (12 vols.). Find it here. You can find my other Logos reviews here.