When I was a vocational youth minister, I tried to help young people (and myself) read the Bible not just for information, but for transformation. I had a number of zealous starts in my own teenage years with an overly ambitious Bible-reading plan, only to find by January 22 that no, I can’t actually read and absorb three chapters a day. This is not to disparage Bible-reading plans, even ones that have you reading through the whole Bible in a year, but it is to say that it’s all too easy to just read the Book for the sake of being able to say, “I’ve read it.”

When I was a vocational youth minister, I tried to help young people (and myself) read the Bible not just for information, but for transformation. I had a number of zealous starts in my own teenage years with an overly ambitious Bible-reading plan, only to find by January 22 that no, I can’t actually read and absorb three chapters a day. This is not to disparage Bible-reading plans, even ones that have you reading through the whole Bible in a year, but it is to say that it’s all too easy to just read the Book for the sake of being able to say, “I’ve read it.”

Andrew Root, author and professor of family and youth ministry at Luther Seminary, makes a similar suggestion. In Unpacking Scripture in Youth Ministry, he offers a short volume of “dogmatic theology written through youth ministry.” The book is part narrative, part theological mini-treatise, and follows the story of a fictional youth worker named Nadia. Throughout the book Nadia wrestles with her own views on Scripture, how to engage youth in Bible reading, and how to respond to the parents, pastors, and facilities committee members with whom she is in community.

The book is just over 100 pages and part of a larger series called A Theological Journey Through Youth Ministry. (See the other three volumes here.) A blend of fictional narrative and theology is hard to pull off in any book, but the transitions here between the two are smooth. From the very beginning scene (Nadia is called at 7 a.m. by a not-entirely-happy facilities coordinator at the church), Root’s storytelling is compelling, funny, and sometimes painfully relatable. Nadia is not the only youth minister, I’m sure, to have been grilled on her biblical theology by the building and grounds committee.

There are discussion questions for each chapter at the back of the book, which would make it easy for a youth minister to lead a team of volunteer leaders or staff through it. Unpacking Scripture and its series fill a gap in youth ministry literature–it’s great to see serious theological reflection coupled with practical application (and done creatively with Nadia’s narrative throughout).

Insatiable Interpreters

Root makes a fascinating point (that I’m still mulling over): “Today, access is more important than memory; we surrender our memory over to gigabytes.” Youth, then, and youth ministers should not see the Bible as a source of knowledge, Root suggests, but as a locus for the construction of meaning. Young people are insatiable “hermeneutical animals,” so Root warns against “frozen biblical knowledge,” since “adolescents interpret everything” in life anyway. He calls for youth ministers to ask:

What does this text mean in the midst of my life? And what does it mean in relation to my existence between possibility and nothingness? What does it say to this struggle I know in the world and in my bones? And…What does this text mean in relation to how God is moving and acting?

Root uses the story in Acts 8 of Philip and the eunuch to unpack his own vision of how to read and interpret the Bible. Philip, he writes, “is not only concerned with helping the eunuch understand the text, he wants to help the man experience it next to his own existence.” Right on.

100% Human, and…?

Root, in his chapter, “The Authority of Scripture,” leads off by talking about the paradox of Christ’s two natures–fully human and fully divine. He uses that as a springboard to look at “the Bible’s two natures,” which I expected to be an articulation of its having been written by human people (who were all too human) who were yet divinely inspired to write. However, Root goes farther than I’m comfortable accepting by saying that the “contradiction of the Bible is that the story of the divine action comes to us in a book that is simply, and profoundly human.” The Bible “contains all the shortcomings and fallibilities of any written text.” And, “The Bible is a 100 percent human book.”

I would have been on board, had he followed up with the ways in which the Bible is also “100 percent divinely inspired” or “breathed-into,” etc., but the emphasis seems to be largely on its human production. To be fair, this “human book,” Root notes, “is essential for encountering the living God,” but other than Acts 8, there wasn’t much discussion about what the Bible says about itself (with due respect to all the footnoted Barth). If this Word is “living and active,” and capable of transforming us (because it is God’s Word/words), doesn’t its inspiration go beyond just the fact that it is a “witness,” the purpose of which “was to reveal God’s action by articulating what God has done”? In other words, could there also be something about these very words that can transform? (Darrell W. Johnson, in his book The Glory of Preaching, notes, “[T]he word of the living God is a performative word” (my italics).)

I would have been on board, had he followed up with the ways in which the Bible is also “100 percent divinely inspired” or “breathed-into,” etc., but the emphasis seems to be largely on its human production. To be fair, this “human book,” Root notes, “is essential for encountering the living God,” but other than Acts 8, there wasn’t much discussion about what the Bible says about itself (with due respect to all the footnoted Barth). If this Word is “living and active,” and capable of transforming us (because it is God’s Word/words), doesn’t its inspiration go beyond just the fact that it is a “witness,” the purpose of which “was to reveal God’s action by articulating what God has done”? In other words, could there also be something about these very words that can transform? (Darrell W. Johnson, in his book The Glory of Preaching, notes, “[T]he word of the living God is a performative word” (my italics).)

Maybe I’m splitting hairs here, and I don’t know Root personally–I suspect that given more pages, or over a cup of coffee, he might say more about the divine inspiration of the Bible, or about its performative power. But I thought at least this book may have put too much emphasis on the human element, as it described “what the Bible is not” and “what the Bible is.”

What is the Goal in Youth Ministry?

Where I find myself agreeing with Root is in his articulation of the goal of youth ministry in relation to Scripture:

So our goal in youth ministry is not to get kids to know the Bible, but for them to use the Bible–to become familiar with its function–so they might encounter the living God, participating in God’s own action through its story.

Of course, the goal in youth ministry could/should be both of those things. We want young people to know the Bible and know how to use it, just as Root describes the eunuch’s both understanding and experiencing Scripture. Youth ministers will still need to help young people differentiate between genres (just as English teachers do) and help them know how to dig into the historical background of a text, which often helps to explain it more than just a surface read.

So we need to get both “behind the text” (“boring” or not) and “in front of the text” to be faithful interpreters. To say, as Root does, that the Bible “only can live, then, by being drawn into our world, into the world in front of the text” has the potential to turn into a me-centric way of reading.

Perhaps the length of this review is an indication that Root has succeeded in getting ministers to think about their own views of Scripture, and how they would engage others in reading the Bible. That is a good thing! I’m not sure I would use this book for youth minister training, since there’s a good deal I’d feel compelled to qualify or further nuance. (Though it’s hard to think of an alternative book along similar lines to suggest.) Unpacking Scripture in Youth Ministry has, however, very much provoked me to a great deal of reflection. I hope that Root continues to write more about theology, Scripture, and youth ministry, and that others follow suit.

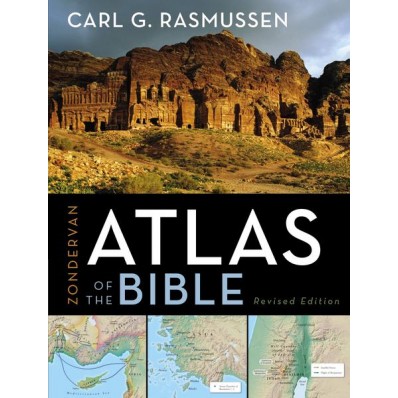

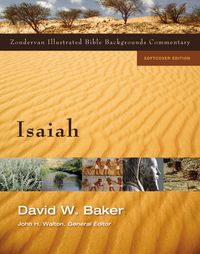

Thanks to Zondervan for the review copy, given without expectation as to the nature and content of this review. The publisher’s product page is here. You can find it on Amazon here. A sample .pdf is here.