Now that I’ve been preaching through the early sections of Matthew for 10 weeks, I’ve had a chance to make regular use of a number of commentaries. I continue to value Zondervan’s Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. Its Matthew volume is very much on par with the rest of the series (which I’ve reviewed here, here, and here). Author Grant R. Osborne primarily intends it for preachers, but I’ve seen it assigned as a seminary textbook, as well.

ZECNT Layout

Matthew, like the rest of the ZECNT series, includes:

- The full Greek text of Matthew, verse by verse, or often split up phrase by phrase

- The author’s English translation

- First, appearing in the graphical layout for the entire passage

- Second, verse by verse or phrase by phrase, next to the Greek

- Matthew’s broader Literary Context for each passage

- An outline of the passage in its immediately surrounding context

- The Main Idea (probably the first place preachers would want to look)

- Structure and Literary Form (with focus on source criticism)

- A more detailed Exegetical Outline of the passage under consideration

- Explanation of the Text, which includes the Greek and English mentioned above, as well as the commentary proper

- A concluding Theology in Application section

This sounds like a lot, but the result is not a cluttered commentary. Rather, as one gets accustomed to the series format, it becomes easy to quickly find specific information about a passage. The section headings are in large, bold font.

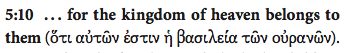

The Greek font is aesthetically pleasing and readable. Here’s a picture:

Osborne’s Introduction to Matthew

For a commentary of more than 1,000 pages, the introduction is surprisingly short (27 pages). Seven of those pages are a section called, “How to Study and Preach the Gospel of Matthew.” Osborne acknowledges,

[T]he details I chose to include in this commentary, both exegetical and theological, were chosen on the basis of one major question: What would I want to know as a pastor preparing a sermon on this passage?

So it’s fitting that he speaks directly to preachers at the very beginning of his introduction. He suggests understanding the Gospels as “history seen through theological eyes” and encourages the preacher to try to grasp the distinct “theological purposes of each [Gospel] author.”

Though the introduction is short, and someone doing extended work on Matthew will need to also look elsewhere for introductory concerns, Osborne is able to give an informative enough overview of dating, authorship, genre, purpose, audience (the thinnest subject in the introduction), sources, history, Matthew’s use of the Old Testament, and structure.

There are also more than 20 pages at the end of the commentary that cover the theology of Matthew. Although that section is tucked away, it’s not to be missed, especially Osborne’s coverage of Christology and of discipleship.

The Commentary Proper: Highlights and Observations

There is just enough Greek (grammar and word studies) to keep one’s Greek sharp. There’s not the level of detail found in the Baylor Handbook on the Greek Text series, which does not yet have a Matthew volume.

Matthew 13:54 begins, “He came into his hometown and began teaching (ἐδίδασκεν) them in their synagogue.” In the commentary you’ll find comments like this one:

The imperfect ἐδίδασκεν could refer to an ongoing practice but is probably ingressive, “began teaching” on this occasion (as in v. 8).

Osborne is sensitive to larger biblical context and theology–even in explaining individual words–so that one gets, for example, a fairly robust explanation of the “righteousness” Jesus talks about fulfilling in Matthew 3:15. And here is Osborne’s take on the “peacemakers” that Jesus calls blessed in 5:9:

The term “peacemaker” only appears elsewhere in verb form in Col 1:20, where Jesus made peace by his blood on the cross, but the concept is found often (Ps 34:14; Isa 52:7; Rom 12:18; 14:19; Jas 3:18; Heb 12:14; cf. 1 En. 52:11). This connotes both peace with God and peace between people—the latter flows out of the former. Jesus is the supreme peacemaker, who reconciles human beings with God through the cross (Col 1:20), so the supreme peacemaking is the proclamation of the gospel.

The graphical layout remains one of my favorite parts of the series. Look at Matthew 13:54-58 (from which the comment above is taken):

It’s readily apparent how Osborne sees the parts of a passage working together and relating to one another.

By way of critique, even with the commentary’s length there were times when I wanted more coverage. The “Explanation of the Text” section for Matthew 5:38-42, for example, barely covered two pages. The single paragraph on “turn the other cheek” addressed the main points that most other commentaries do, but given how many Christians have wrestled through this important passage (both on paper and in action), more could have been said.

Conclusion

Osborne succeeds in keeping the preacher in view throughout the commentary. I’ll give one last example, since this typifies Osborne’s blend of research and presentation in a way that will both assist and inspire preachers and teachers. In Matthew (and Luke) the Lord’s Prayer that Jesus gives his disciples to pray does not have the ending it does when prayed in liturgical settings (“for thine is the kingdom…”). Whether this should make it into a sermon or not is another question, but Osborne anticipates that readers and preachers will at least be wondering about it. He writes:

The traditional doxology (“for yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen”) appears in only a few late manuscripts (L W Θ 0233 et al.), and several of the best manuscripts end here (א B D Z et al.), with a variety of endings in others. This makes it almost certain that it is not original. It is possible that churches added their own doxology when praying this prayer, and this one emerged as the best summary of the contents of the prayer. However, it (and the other endings) is based on 1 Chr 29:11 – 13 and is meaningful, so it is not wrong to utter the ending as a personal prayer.

Where does the Matthew ZECNT volume rate among Matthew commentaries for preachers? Definitely toward the top. I still go to R.T. France’s NICNT volume first. And for Greek and history of interpretation, John Nolland (NIGTC) covers more territory. But Osborne’s constant eye on the larger literary context, the detailed structural outlines, the inclusion of Greek and English texts, the Theology in Application sections, and the graphical layout make his commentary a welcome guide for preaching and teaching through the First Gospel.

Thanks to Zondervan for the review copy. You can find the book’s product page here. It is on Amazon here. Amazon links above are affiliate links that help further the work of this blog, described here.

3 thoughts on “Matthew (Zondervan ECNT), reviewed”