Ask a group of pastors, seminarians, professors, or serious Bible readers, “What one commentary series on the Old Testament would you most recommend?” and you’re likely to hear: “NICOT.” Eerdmans’ New International Commentary on the Old Testament blends scholarship with application in a readable and engaging manner. Few, if any, commentary series are consistently this good throughout the series. And I don’t know of any other series that has such broad ecumenical appeal.

Ask a group of pastors, seminarians, professors, or serious Bible readers, “What one commentary series on the Old Testament would you most recommend?” and you’re likely to hear: “NICOT.” Eerdmans’ New International Commentary on the Old Testament blends scholarship with application in a readable and engaging manner. Few, if any, commentary series are consistently this good throughout the series. And I don’t know of any other series that has such broad ecumenical appeal.

NICOT in Olive Tree has 23 volumes, spanning 26 biblical books. The bundle includes the 2010 volume on Hosea. The only volume currently in print that is not here is The Book of Judges, by Barry G. Webb (2012). (Judges is not available in any other Bible software at the moment.)

General editor Robert L. Hubbard Jr. writes of the series:

NICOT delicately balances “criticism” (i. e., the use of standard critical methodologies) with humble respect, admiration, and even affection for the biblical text. As an evangelical commentary, it pays particular attention to the textʼs literary features, theological themes, and implications for the life of faith today.

As I preached through Isaiah this past Advent, John N. Oswalt’s two volumes on that book were the first commentary I turned to after spending time with the biblical text. While it was always clear that Oswalt knew Isaiah and his milieu well, the author would find himself swept up at times in praise of the God Isaiah preached. On Isaiah 2:2, for instance, he writes:

What Isaiah was asserting was that one day it would become clear that the religion of Israel was the religion; that her God was the God. To say that his mountain would become the highest of all was a way of making that assertion in a figure which would be intelligible to people of that time.

On that passage’s promise of peace among nations, he concludes:

On that passage’s promise of peace among nations, he concludes:

Until persons and nations have come to God to learn his ways and walk in them, peace is an illusion. This does not mean that the Church merely waits for the second coming to look for peace. But neither does it mean that the Church should promote peace talks before it seeks to bring the parties to a point where they will submit their needs to God.

Oswalt is representative of the authors in NICOT, in that he loves the text (and its grammar, history, and background) and loves the God who inspired it.

NICOT in Olive Tree has hyperlinks to biblical references and commentary footnotes, which you can easily and quickly view in the Bible Study (computer) app through the Quick Details corner (by hovering over the hyperlink), or as a pop-up window (which can then also pop out and keep your place in a separate window). It’s just as easy to tap a hyperlink in the mobile app.

There are two ways I’ve used NICOT so far.

1. I use NICOT as my starting point in the main window.

After some time in the biblical text, I have made my way through parts of NICOT by starting from the commentary. I can use hyperlinks to read the verses being commented on, as well as any other references. I can keep a Bible open in the split window and have it follow me along as I read through NICOT.

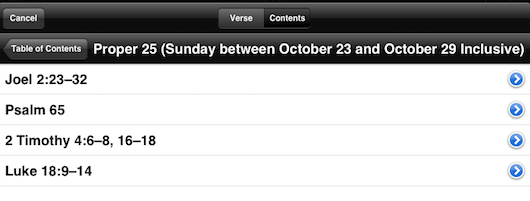

Using NICOT this way, there are quite a few ways to get around, both by looking up a verse in the commentary, and by navigating its Table of Contents. You only need to use one of these options at a time, but here they all are:

Note that from the Go To drop-down menu, I can keep following the sub-menus till I get to a specific place in the commentary (Introduction to Malachi in the instance above). One could also do this from the Go To item in the toolbar, which allows for both verse searching and Table of Contents navigation.

2. I use the Bible in the main window and NICOT as a supplement in the split window.

This has the advantage of letting me use NICOT as one among multiple resources in the Resource Guide, as shown (in part) here:

In both of the above setups you can take notes in NICOT, highlight, and bookmark your place. You can also do a search on a word or phrase in the commentary, with the results appearing almost instantaneously. One may wish, for example, to find all the times Oswalt refers to the “Suffering Servant” in Isaiah, which is an easy and fast search to run.

In reviewing Olive Tree I have found it to have the most versatile, smooth, and customizable Bible app I’ve seen on iOS. I write more about the Bible Study iOS app here. The fact that Olive Tree is cross-platform makes it appealing to many. Though the desktop app is well-designed, I would like to see a future update where you can create a saved workspace with multiple resources open in various tabs and windows. That, I think, would take the app to the next level.

But everything is here to help you work through NICOT in a way that you couldn’t in print. There are a couple of options (one free and one paid) for Hebrew Bibles, too, if you want to use NICOT in tandem with the original language. (NICOT uses transliterated Hebrew.)

NICOT volumes consistently top the charts of the Best Commentaries site. Preachers and professors, parishioners and pupils will all find much to mine here, as they seek to better understanding the Old Testament and to more faithfully love the God whose goodness its pages proclaim.

Thanks to Olive Tree for the New International Commentary on the Old Testament (NICOT), given to me for this blog review, offered without any expectations as to the content of the review. You can find the product here. For a little while longer, it’s $349.99 for the series, which is 50% off its regular price.