This is a meta-review of sorts: a review of a book that briefly reviews commentaries for each book of the Old Testament. I.e., here are some words on some words on some words on the Word.

Here is the publisher’s book description:

Leading Old Testament scholar Tremper Longman III provides students and pastors with expert guidance on choosing a commentary for any book of the Old Testament. The fifth edition has been updated to assess the most recently published commentaries, providing evaluative comments. Longman lists a number of works available for each book of the Old Testament, gives a brief indication of their emphases and viewpoints, and evaluates them. The result is a balanced, sensible guide for those who preach and teach the Old Testament and need help in choosing the best tools.

It’s a recurring question: What are the best Old Testament commentaries to get? To help answer that question, Longman rates an impressive host of commentaries on a 1-to-5 star scale:

One or two stars indicate that the commentary is inferior or deficient, and I discourage its purchase. Four or five stars is a high mark. Three, obviously, means a commentary is good but not great. I also use half stars in order to refine the system of evaluation.

One nice touch in this book is that all of the five-star commentaries are separately listed in an appendix in the back. Students or pastors looking to build a library might start there. Before turning to commentaries on individual books of the Bible, Longman briefly reviews one-volume commentaries (though this one is absent) and “commentary sets and series.” In addition to the stars, Longman notes whether a book is better suited for a layperson (L), minister/seminary student (M), or scholar (S), or some combination of those three.

To have a rating system is good, but there are some odd ways in which it is applied. One unlucky book got “no stars” on what the 1-to-5 star scale. And the comments (a paragraph’s length) under each commentary don’t always seem to match the rating. For example, a commentary on 1 Chronicles that has “a very helpful discussion of all aspects of the book” and other positive evaluation from Longman receives only 2.5 stars. A Genesis commentary whose author “shows great exegetical skill and theological insight” then receives 1.5 stars. As does another whose author “is insightful and knowledgeable.” One series receives four stars as a whole, but one of the individual commentaries that is “definitely one of the best volumes in the series thus far” receives just three.

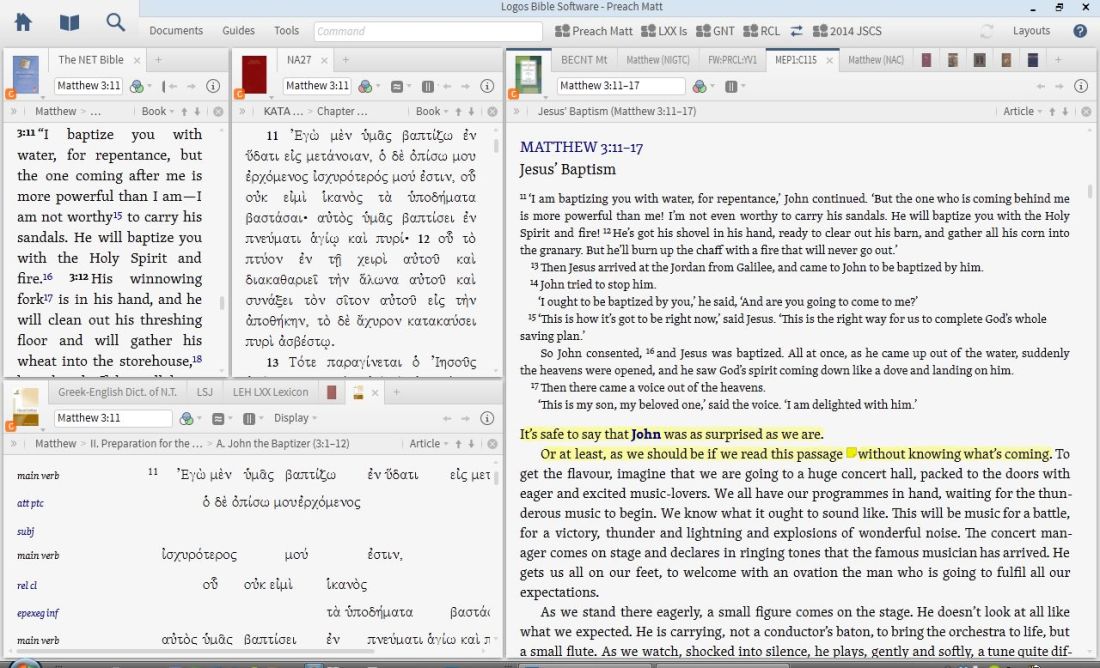

There are also some things that were missed in updating the 2007 fourth edition to this 2013 fifth edition. The Berit Olam series was “just under way” in the fourth edition, and is so here, too. The New American Commentary series in both 2007 and 2013 editions is “relatively new,” even though it has a number of volumes published in the early 1990s. In the Proverbs section, Fox’s Anchor commentary still only consists of volume 1 (“Hopefully, we will not have to wait too long for the rest of the commentary to appear”), even though volume 2 was published in 2009. And there is also no mention of the Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Text series, which had five volumes published by the time of this new edition of Longman’s work. Also, especially with the proliferation of commentaries now available through Bible software, an appendix covering electronic books would have been nice.

As far as his written evaluation of the commentaries, Longman is especially favorable toward Old Testament commentaries that discuss how a given passage is used in the New Testament. It’s not clear to me that–even for a Christian–this would be a requirement for a good Old Testament commentary, but I see his point, and am disposed to at least somewhat agree. He writes:

I continue to hope that future commentaries produced for use by Christian pastors in the church would include more reflection on how the Old Testament message is appropriated by the New Testament.

But, in my opinion, this criterion is perhaps over-applied, resulting in ratings penalties for what are otherwise strong commentaries, including ones that may have never set out in the first place to discuss the NT use of the OT.

One final critique: though there are not many commentaries on the Septuagint text of the Old Testament, a few series have begun. I can’t totally fault Longman for not having any Septuagint commentaries here, but I had hoped that the few that have been published might have been noted. I think also of John William Wevers’s Notes on the Greek Text series, which covers the Pentateuch.

Longman’s aim is for “this commentary survey [to] help students of the Bible choose the commentaries that are right for them,” and in that he is mostly successful. For example, he lets the reader know which commentaries date a given prophet according to “critical” or “evangelical” interpretations (I’m oversimplifying a bit here). He has helpful comments like, “If you get only one commentary on Joel, this should be it.” I finished this book feeling like I had a general lay of the land of Old Testament commentaries.

Despite a sometimes quirky or inconsistent rating system, and despite what appears to be a not really thoroughly updated volume, Old Testament Commentary Survey is unique, and one I already consult and will continue to consult whenever considering commentaries on a given Old Testament book. I just know I’ll have to supplement it with my own research and with seeking recommendations from others. The book works especially well as an introductory checklist that one can use as she or he is building a library of commentaries.

A sample pdf of the book, including introductory material and Longman’s take on one-volume commentaries and various commentary sets, can be found here.

Many thanks to Baker Academic for the review copy of OT Commentary Survey. You can find it here (Baker Academic) and here (Amazon).