Craig S. Keener’s Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary utilizes two particular approaches to Matthew:

[A]nalysis of the social-historical contexts of Matthew and his traditions on one hand, and pericope-by-pericope suggestions concerning the nature of Matthew’s exhortations to his Christian audience on the other.

Keener is behind the ever-useful IVP Bible Background Commentary, now in a revised edition. And his exegetical commentary on the first two chapters of Acts is more than 1,000 pages, not counting the bibliography and indeces. Quantity does not always mean quality–it’s harder to write less than more, most of the time–but one can rightly expect Keener to be both thorough and insightful.

Let me jump right in with why I like (and trust) his Matthew commentary.

Layout Matters

The Gospel of Matthew is one of the best laid out commentaries I’ve used. The section on the Lord’s Prayer (“The Kingdom Prayer,” as Keener has it) is a good example. There’s a bold heading with an introduction to the prayer. Here Keener compares the prayer in Matthew to the version in Luke, while offering explanations as to why the two forms differ slightly. Then Keener goes through the passage phrase-by-phrase in eight parts, with the summary statement for each of the parts in bold.

For example, he writes, “Second, the prayer seeks first God’s glory, not the petitioner’s own needs….” Then he uses italics for key questions or insights in each of the eight parts of the prayer. As here: “What did it mean in a first-century Jewish context for God’s name to be hallowed in the future?”

The result is a commentary that is highly scannable and readable. Just the simple use of bold and italics, throughout the book, helps orient the reader to what Keener is doing–not to mention offers some really good ideas for how to preach or teach on the text. The layout also makes it easy to get a quick, cursory overview of how Keener understands a given passage.

Matthew, According to Keener

Keener’s humility is refreshing, as he writes that, “in contrast to [his] earlier opinion,” he is:

therefore presently inclined to accept the possibility of Matthean authorship on some level, although with admitted uncertainty. Perhaps the most probable scenario that incorporates the best of all the currently available evidence is the presence of at least a significant deposit of Matthean tradition in this Gospel, edited by the sort of Matthean school scholars have often suggested (though I believe the final product is the work of a single author, not a “committee”).

His judicious weighing of the consideration for and against actual Matthean authorship will allow the reader to have an informed opinion. Does it matter?

Yet what we do conclude about the author does affect our understanding of the Gospel. Matthew is clearly Jewish, in dialogue with contemporary Jewish thought, and skilled in traditional Jewish interpretation of the Old Testament…. Matthew also knows the context of his citations much better than many modern readers have supposed…, and he demonstrates familiarity with a variety of text-types….

On author and intended audience, Keener concludes:

Concurring with the perspectives of what is still probably the minority view, I find in the Gospel an author and audience intensely committed to their heritage in Judaism while struggling with those they believe to be its illegitimate spokespersons. On this reading, Matthew writes to Jewish Christians who, in addition to being part of their assemblies as believers in Jesus, are fighting to remain part of their local synagogue communities.

The introductory material covers the rest of the expected territory: dating, rhetoric, social settings, Gospel sources, the use of narratives in the early church, structure, and more. I found the introductory sections on Jesus (as teacher, as prophet-healer, as Messiah/King, as Son of God) especially illuminating for understanding Matthew as a whole. Keener also has a couple pages upfront about Matthew’s important “Kingdom of Heaven” theme, including this gem:

In short, the present significance of the future kingdom in early Christian teaching was thus that God’s people in the present age were citizens of the coming age, people whose identity was determined by what Jesus had done and what they would be, not by what they had been or by their status in the world.

Though the commentary is academic in nature, it also “will preach” pretty well, as Keener’s lines above make clear.

A Few More Highlights

As soon as picking up the commentary, one will want to read the Excursus on Pharisees (p. 538) and Excursus: Was Jesus Executed on Passover? (p. 622).

One should not expect to find lexical or grammatical comments on each keyword or phrase in Matthew. The comments on Matthew 6:25-34, for example, do not address the meaning of the oft-repeated “worry.” Keener points out that Jesus utilizes the Jewish qal wahomer (“How much more?”) argument to show God’s care for “people in his image and for his own beloved children.” That insight itself is in most commentaries already, but Keener goes further and covers yet more rhetorical territory:

Greek philosophers sometimes disdained such bodily needs altogether, complaining that their bodies were prisons because they were dependent on food and drink (Epict. Disc. 1.9.12) and advising that one turn one’s mind to higher pursuits (Marc. Aur. 7.16). …Jesus never condemns people for recognizing these basic needs…. Yet he calls them to depend on God for their daily sustenance, a provision that Jewish people considered one of God’s greatest miracles….

Keener consistently breaks passages down into main points, which helped me see both the flow of Matthew’s narrative and think about how I could apply each passage. For example, in Matthew 20:29-34 (“Persistent Prayer”) two blind men receive their sight when Jesus’ compassion leads him to heal them. Keener’s four sentences in bold (with a paragraph explanation after each) are:

First, these suppliants recognized the identity and authority of the one whose help they entreated (20:30).

Second, they refused to let others’ priorities deter them (20:31).

Third, Jesus’ compassion was the ultimate motivation for his acting (20:34).

Finally, recipients of Jesus’ gifts should follow him (20:34).

This 2009 edition is not essentially different from Keener’s 1999 Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. (I.e., the Socio-Rhetorical Commentary is not a revised edition, per se.) There is, however, an addendum at the front of the commentary called, “Matthew and Greco-Roman Rhetoric.” Here Keener goes chapter-by-chapter through the book of Matthew and adds his recent insights into how Jesus and Matthew make use of known rhetorical practices in their teaching and writing, respectively. In the end, though, Keener finds that Jewish rhetoric offers “much closer analogies…than Greek or Roman rhetorical handbooks do.”

Finally, if you’ll permit me one more quotation of Prof. Keener, here is an example of the inspiring nature of his commentary:

But above all the teaching towers the figure of Jesus himself: King, Messiah, Son of Man, the rightful Lord of Israel whom their people would one day acknowledge (1:21; 23:39). The final judge, the true revelation of the Father (11:27), was the meek and lowly One who had walked among the first disciples and died for his people (11:29; 20:28; 21:5), the One who would also empower Matthew’s readers to fulfill the task he had given them (10:19-20; 11:28-30).

Bonus: The Bibliography

It may be strange to praise a book for its bibliography, but Keener offers 150 pages of bibliography on Matthew. Keener seems to not leave any stone unturned, whether it’s another commentary, monographs, or journal articles. He writes, “The purpose of this commentary does not allow me to summarize and interact in detail with all secondary sources on Matthean research.” And yet one would be hard-pressed to find a more thorough list of secondary sources for Matthew elsewhere. In this regard, Keener is successful in offering a commentary that “will contribute to further research.”

The reader should realize that, as noted above, though this commentary was published in 2009, it was not really a revision of the 1999 volume, so the bibliography has not been brought into the 21st century with any updates. (So Nolland and France, for example, are not listed.)

The commentary’s Index of Ancient Sources is 142 pages, taken “from a variety of narrative genres to illustrate Matthew’s narrative techniques, with special attention to ancient biography and historiography.” Copious references throughout the commentary give the researcher multiple good leads.

For all of Keener’s thoroughness, the use of bold and italics for main points keeps the commentary well-organized, so that the research does not become overwhelming. Keener’s heart seems to be pastoral, and his reverence toward the Jesus of Matthew is clear and an inspiration throughout the commentary.

You don’t need any Greek to use this commentary, but a good cup of coffee and a full night’s rest might help, as it can be dense and detailed (but not impenetrable) in places. The reader of Matthew who is willing to work at Keener’s commentary will be rewarded. This volume has already vaulted its way into my top four Matthew commentaries.

Thanks to Eerdmans for the review copy. You can find the book’s product page here. It is on Amazon here. Amazon links above are affiliate links, described further here.

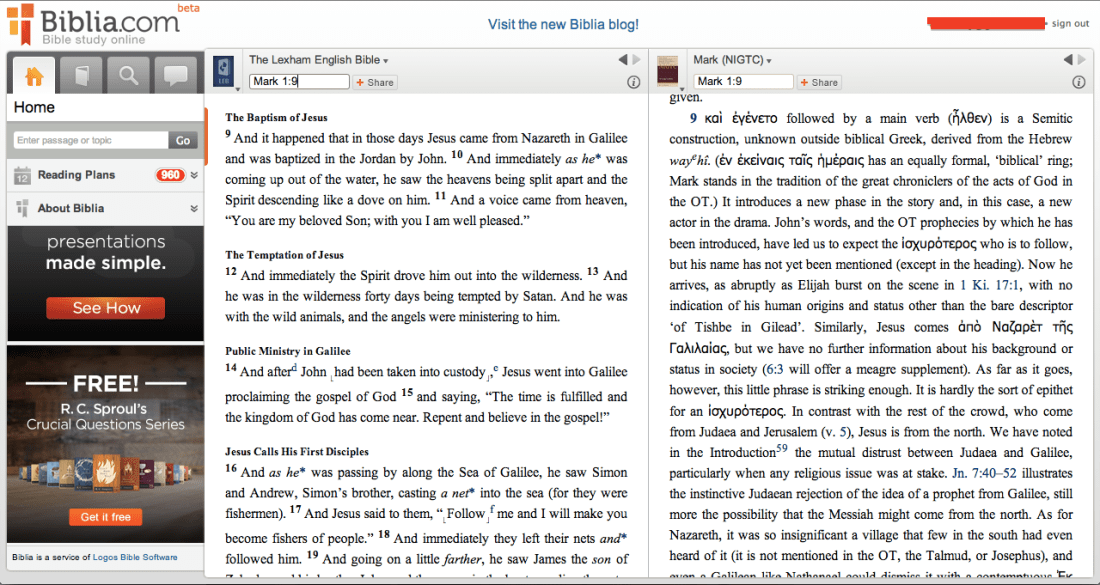

For an exegesis course in seminary, I was assigned R.T. France’s Mark in the New International Greek Testament Commentary (NIGTC) series. The assignment was to read the entire commentary that semester, and I read every one of its 700+ pages. It was that good.

For an exegesis course in seminary, I was assigned R.T. France’s Mark in the New International Greek Testament Commentary (NIGTC) series. The assignment was to read the entire commentary that semester, and I read every one of its 700+ pages. It was that good.