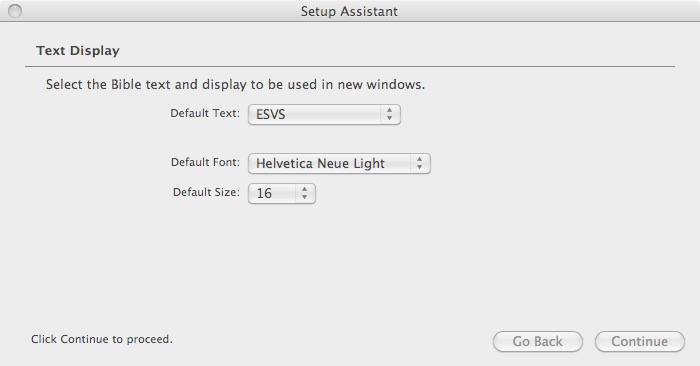

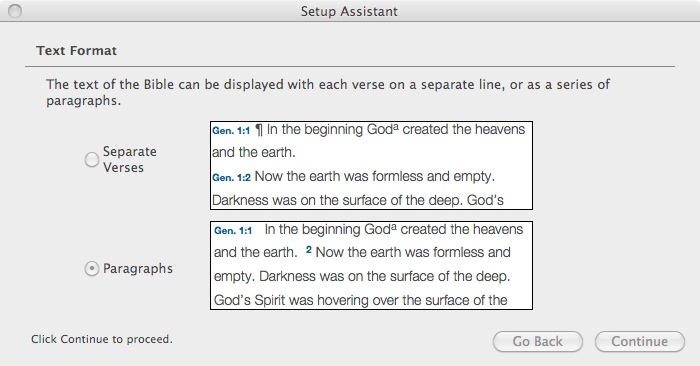

I am a new Accordance user. As I said in the first part of my review of Accordance: so far, so good.

I’m working my way through some of Accordance’s training materials so I can better utilize the program as I review it. Here is Episode 77 of their Lighting the Lamp podcast series. It is at the “basic level” and provides a “first look” at Accordance 10. It’s a good place to start.

Here I highlight, in no particular order, four cool features in Accordance 10. Each of these not only has a bit of a wow factor, but will also enhance my study of the Bible, especially in its original languages.

1. Pie charts, bar charts, statistics, oh my!

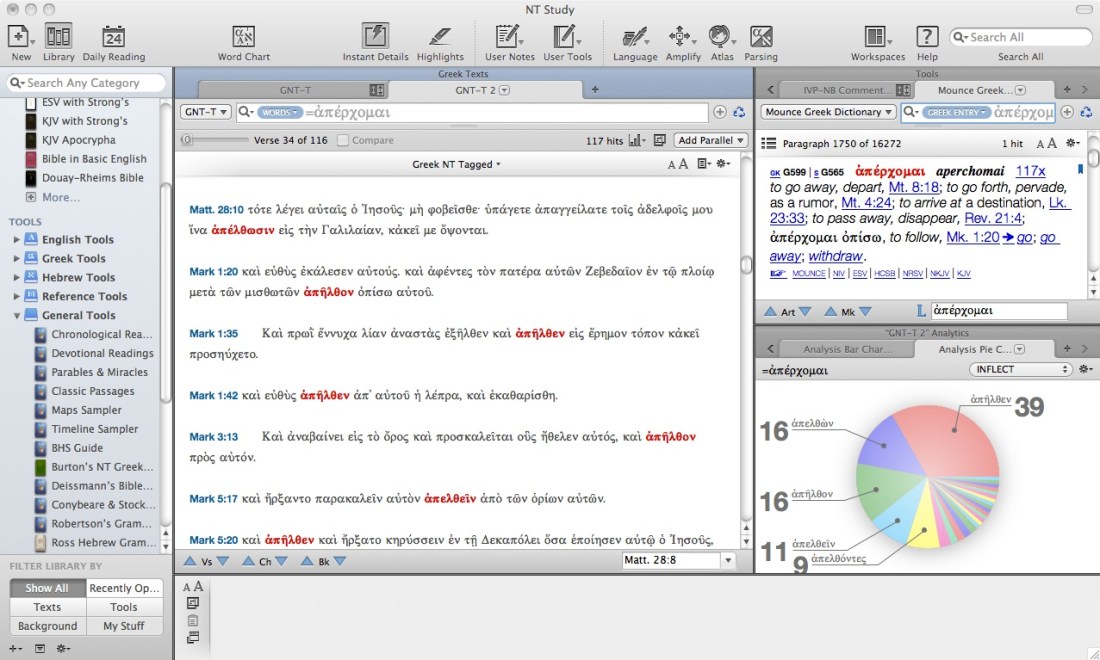

In Mark 1:42 I read: καὶ εὐθὺς ἀπῆλθεν ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ ἡ λέπρα, καὶ ἐκαθαρίσθη. (Note: I simply checked off a box in Preferences and was able to export this Greek text as unicode from Accordance into WordPress.) Then I “right click” on ἀπῆλθεν, select “Search For… Lemma,” and I can see all its New Testament occurrences pop up in a separate window. It also notes just under the search bar that my search results in 117 hits. The empty box at the bottom is the “Instant Details” window that shows parsing information when I hover over a word. See below and click for larger or open in a new tab:

You can see I have Mounce’s Greek Dictionary open at top right. This already includes word statistic information. But–and here’s cool feature #1–check out the “Analysis Pie Chart” at bottom right! This shows the ways and number of times ἀπέρχομαι is variously inflected. Or you can see it in bar chart form, which in this case affords a bit more detail than the pie chart:

I quickly discover, in a visually appealing way, that my word at hand (ἀπῆλθεν) is the most common inflection of ἀπέρχομαι. This analysis tool allows multiple configurations. You can search by inflection, gender, tense, person, etc.

2. Customizable Toolbar

This has so far been one of the things about Accordance I’ve appreciated the most. New to Accordance 10 is the customizable Toolbar. Mine looks like this at the moment:

Users can easily add and re-arrange what they want in the toolbar, simply by “right clicking” in the toolbar area and going from there. (Note: “right clicking” for me on my Mac is just a two finger tap on the trackpad.) Right clicking on the toolbar allows you to customize it, which then gives you this:

Then, simply set it up how you want it. You can always revert back to the default, as noted at the bottom. The “separator” and “space” options are an especially nice touch. See the Accordance blog post here for more ways a user could customize Accordance 10.

3. Magnify this zone

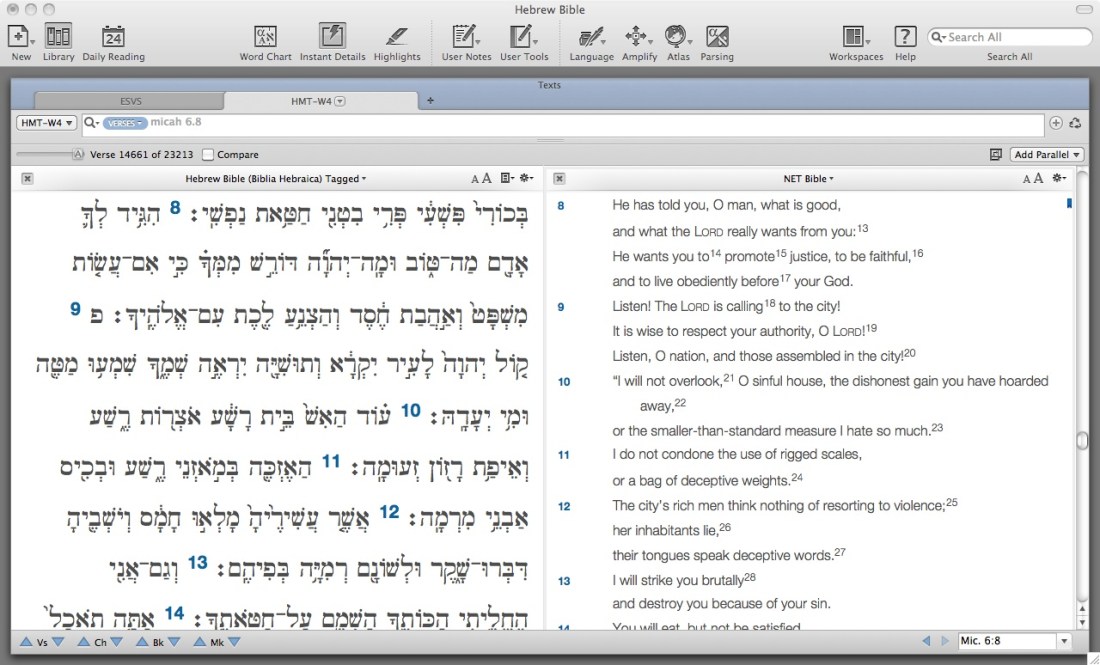

Here’s a setup I’ve been using to work through the Hebrew text. You’ll note my library on the left, the Hebrew Masoretic Text side-by-side with the NET Bible in the middle, the Instant Details (parsing) box on the bottom, and the dictionary pane on the right. That’s a good setup for analyzing my way through the text. But if I just wanted to read the Hebrew (with the English next to it) with no other distractions, I easily could, without losing my other windows. “Magnify this zone” allows me to turn this:

into this:

With a single click I can easily return back to my full setup when I’m done.

4. A great one-volume commentary, and a great Bible dictionary

Both the Starter Collection in Accordance and Original Languages Collection (what I’m reviewing) come with the IVP New Bible Commentary and the Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. The IVP Commentary is integrated into the program such that you can have it sync with you through a passage while you read and study. Each of these is a handy resource to have at the ready while working through text.

My only complaint with these has been that the IVP commentary is a “Reference Tool” while the Eerdmans dictionary is an “English Tool.” This means that they’re in two separate places in the library, which wasn’t totally intuitive for me right away. However, this separation may be due to the fact that–from what I can tell–Reference Tools follow you with verse-by-verse integration whereas you have to do a specific look-up by word for the English Tools. All the same, it’s great having access to these texts.

There are more cool features in Accordance 10. I’ll continue to review the program in coming days. You can go here for an overview of some of Accordance’s newest features.

This series of reviews is made possible by my having received a review copy of Accordance 10, Original Languages Collection. I have not been asked or expected to provide a positive review–just an honest one. Part 1 of my review of Accordance 10 is here. UPDATE: Part 3 of my review is here. UPDATE 2: Here is part 4, a review of the Original Languages Collection. UPDATE 3: Here is part 5, “Bells and Whistles.” UPDATE 4: part 6, “More Bells and Whistles.”