James is no “epistle of straw,” as Martin Luther once (in)famously said of the book. But many–with Luther–find it difficult to reconcile Paul and James on faith and works.

James is no “epistle of straw,” as Martin Luther once (in)famously said of the book. But many–with Luther–find it difficult to reconcile Paul and James on faith and works.

Paul: “A person is justified by faith apart from works of the law.”

James: “A person is considered righteous [i.e., justified] by what they do and not by faith alone.”

Here I review James by Craig L. Blomberg and Mariam J. Kamell, from Zondervan’s Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (ZECNT) series. (Click here to find my review of Luke in that same series; below I use some of my same wording from that post to introduce the ZECNT series more generally.)

Like the rest of the ZECNT series, James is “designed for the pastor and Bible teacher.” The authors assume a basic knowledge of Greek, but Greek is not required to understand the commentary. For each passage the commentary gives the broader literary context, the main idea (great for preachers!), an original translation of the Greek and its graphical layout, the structure, an outline, explanation, and “theology in application” section.

The introduction covers an outline and structure of James, the circumstances surrounding its writing, authorship and date, and significance of the book. It is shorter and less detailed than the introductions in Douglas Moo’s James commentary and that of Peter Davids. Immediately I looked for how the authors would resolve the Paul/James (alleged) discrepancy, but they note in the introduction that they discuss James’s theology after “the commentary proper.” (The ZECNT series has a separate “Theology” section at the back of the book that most other commentaries include as part of the introduction.)

They give just two paragraphs in their theology section–with a bit more in the body of the commentary–to “Faith and Works” (compare Moo’s lengthier discussion in his introduction), but they have their reasons for this:

Contrary to what the extent of the discussion of the topic might suggest, faith and works is not the main focus of James’s letter. It is a subordinate point that grows out of his concern for the poor and the dispossessed (2:14-26; cf. 2:1-13).

I’m a little embarrassed to admit that this idea of faith and works as a subordinate point in James had not really occurred to me prior to working with this commentary. (A good trait in a commentary to produce such thoughts!) But if you click on the references above or look through James 2 (and the rest of James) in your Bible, it’s easy to see where the authors are coming from.

In fact, the “three key topics” in James, according to Blomberg and Kamell, are “trials in the Christian life,” “wisdom,” and “riches and poverty.” They follow Davids here, and note that James 1:2-11 lays out each of the major themes, which James then restates in 1:12-27. 2:1-5:18 then consist of “the three themes expanded,” in reverse order, followed by a closing in 5:19-20.

Blomberg and Kamell are “the first to grant that we may still be imposing more structure on the text than James had in mind.” All the same, their outline of James makes it easier to work through the book, and then finally does, I think, justify their claim in the theology section that “faith and works” is not the central theme of the letter and should be considered in its broader context. Still, they do have a good way forward in understanding Paul and James together: “But this action, these deeds or works, are not put forward in any attempt to merit God’s favor but as the natural, spiritual outgrowth of one’s faith.”

As with Luke, the graphical layout of each passage (in original English translation) is a unique contribution in James. Being able to see main clauses in bold with subordinate clauses indented under them (plus how they relate back to the main clause) gives the reader a quick, visual grasp of the entire passage at hand. See page 45 of the commentary in this sample pdf to see how it looks. This is a highlight of the ZECNT series, and the fact that it’s in English makes it all the more accessible. The translation is smooth and readable, doing great justice to both the Greek it translates and the English language.

James has the full Greek text of James, verse by verse, and the full English translation (passage by passage in the graphical layout, then again verse by verse next to the Greek). As I’ve said before, a value for me in using reference works is not having to pull five more reference works off the shelf to use the first reference work! The authors make comments like this one in 1:5 throughout the work, wedding grammatical and lexical analysis to exegetical application:

We are told to ask of the “giving God” (διδόντος θεοῦ). Here the present participle suggests that “giving” represents a continuous characteristic of God.

To take another example, on James 2:20, which they translate, “Do you want to know, O empty person, that faith without works is workless?” they write:

James incorporates a pun on the word “work” (ἔργον), using the negative adjective from the same root–“workless” (ἀργή). The term can also mean idle or useless. Faith that lacks works does not work! In other words, it is entirely ineffective to save.

Teachers and preachers especially will appreciate the “Theology in Application” section that concludes each passage. James may already strike the preacher as a book that just preaches itself, but the authors do well in helping the preacher connect the text with today’s concerns. For example, for 2:14-17 they note that although James

provides no treatise on the most effective ways to help the poor…, true believers will take some kind of action. At the very least, they must cultivate generous, even sacrificial giving to help the poor as part of their ongoing personal and corporate stewardship of their possessions. But in light of systemic injustice, we probably need to do much more.

Amen. The authors go on, “James certainly would share the concern of liberation theologians to do far more for the poor, individually and systemically, than many branches of recent Christianity have attempted” (my italics). Moo agrees–though he wants to distance himself “from an extreme ‘liberation’ perspective,” he says “we must be careful not to rob his denunciation of the rich of its power.” And James 5:1-6 are pretty damning of the powerful rich who use their power to oppress the poor.

The authors write,

[These oppressors] are the financially wealthy in a world where the rich occupied a miniscule percentage of the population. James does not call them to change their behavior. Instead, he warns them of impending disaster in their lives by commanding them to mourn their coming fate. …”Wail” [ὀλολύζοντες] appears in the LXX of the Prophets in contexts of judgment and can refer to inarticulate shrieks of terror. …James makes it clear that these rich people are going to undergo a terrible ordeal.

There were a few times in the “Theology in Application” section that I wondered (as other reviewers have) whether the authors weren’t getting a bit off-topic from the text. For example, on 3:9-12 they say,

Abortion and euthanasia offend God deeply because they take lives made in his image. But abuse or neglect of the poor and outcast (including the homosexual) proves equally offensive because such treatments likewise demean individuals God made to reflect himself.

They say this to argue against the “stereotypical agendas of both the political and religious ‘right’ and ‘left,'” but it was hard for me to decide whether this was a case of applying an ancient text well to a contemporary set of issues, or if it was an anachronistic stretch. Nothing they say here is incongruent with James, but I did wonder here (and in another place) whether those verses in James really speak to issues like abortion and homosexuality. A minor critique, though.

Those working their way through the Greek of James may still want to have Davids on hand. But as with the Luke volume in this series, the combination of close attention to the Greek text with contemporary application makes James a commentary very much worth using. I know I will want to go back to this commentary right away when I am doing work with the book of James in the future.

(I am grateful to Zondervan for the free review copy of this commentary, which was sent to me with the understanding that I would then write an unbiased review. You can find the book on Amazon or at Zondervan.)

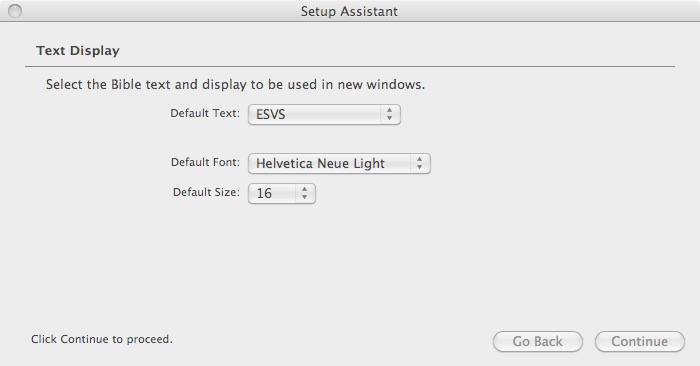

(Although, I confess, I don’t know what “Helvetica Neue Light” looks like off the top of my head! No matter–this can always be changed later.) This next option for text formatting immediately endeared me to Accordance:

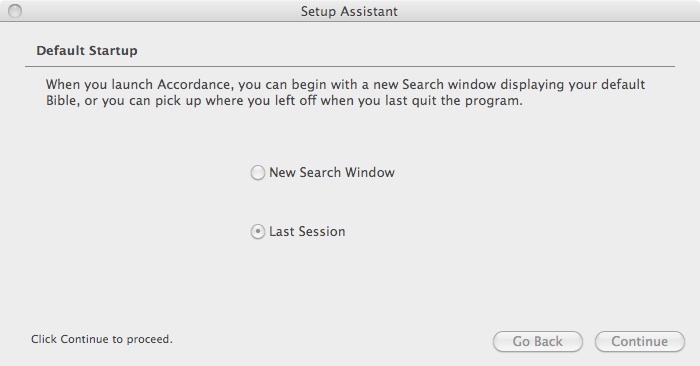

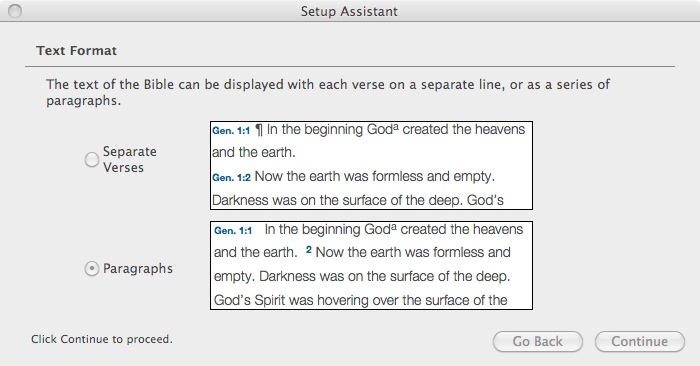

(Although, I confess, I don’t know what “Helvetica Neue Light” looks like off the top of my head! No matter–this can always be changed later.) This next option for text formatting immediately endeared me to Accordance: These are perhaps little things, but Accordance’s customizability seems obvious from the beginning.

These are perhaps little things, but Accordance’s customizability seems obvious from the beginning.