I have been an avid and happy BibleWorks user since version 7 (they are now in version 9). But my first computing love is a Mac. (Too bad for expensive taste in that regard!) I have a cheap PC laptop at home on which I run BibleWorks, but have been interested in exploring Accordance for some time. Now, thanks to the kind folks at Accordance who have given me a copy for review, I can take Accordance for a spin.

I apparently got into Accordance at just the right time. This week they launched an upgrade from Accordance 9 to Accordance 10. And it looks like users are pretty happy with the switch.

In a series of posts, I will offer my review of Accordance 10, Original Languages Collection. In this post I report on my installation process and initial impressions as to the program’s layout and interface.

Download and installation was mercifully fast, even over a wireless Internet connection. In 30 minutes or so I was able to download the Accordance application to my computer and the Original Languages Collection with its various modules.

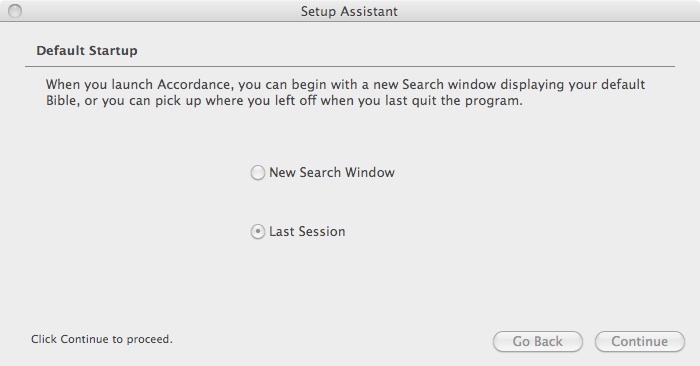

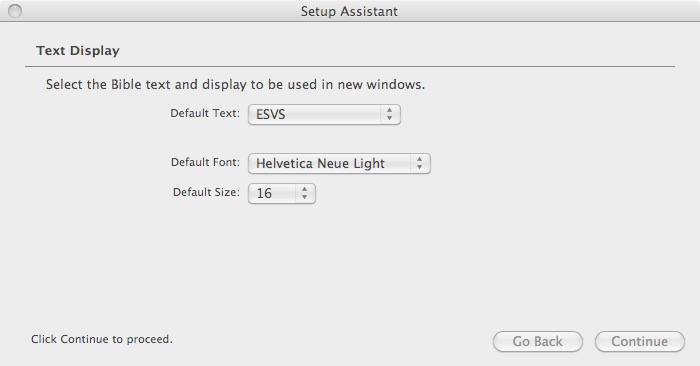

I appreciated the flexibility offered me even in the initial setup. For example, I could make choices at the following spots:

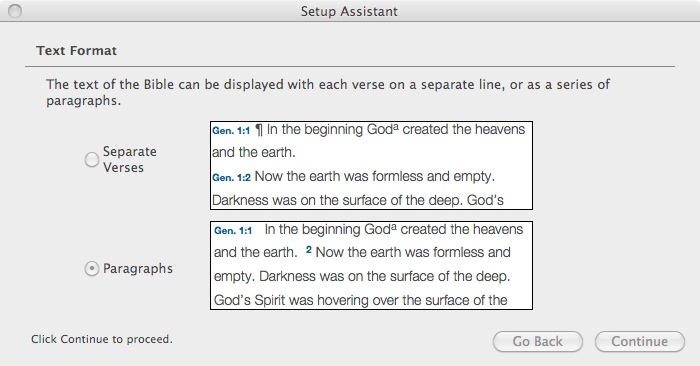

(Although, I confess, I don’t know what “Helvetica Neue Light” looks like off the top of my head! No matter–this can always be changed later.) This next option for text formatting immediately endeared me to Accordance:

(Although, I confess, I don’t know what “Helvetica Neue Light” looks like off the top of my head! No matter–this can always be changed later.) This next option for text formatting immediately endeared me to Accordance:

These are perhaps little things, but Accordance’s customizability seems obvious from the beginning.

These are perhaps little things, but Accordance’s customizability seems obvious from the beginning.

The only snag I hit in installation was being able to install one of the included modules, even after multiple attempts (the BHS Latin Key). Although, taking a look at the forums, I’m not alone. I expect the Accordance team is mighty busy with the new release. Accordance 10 is already in 10.0.1. I don’t think this is a sign of a buggy version released too soon, but rather an indication that the folks behind the software are quick, responsive, and eager to improve upon the program.

Once finishing installation, I played around a bit with my resources, and within just a few minutes and no prior knowledge of Accordance, was able to set things up this way (click image for larger or open in new tab):

On the left you can see my “library” which in this view shows some of the texts that come with the Original Languages Collection. Thing of beauty: it has the New English Translation of the Septuagint. With how often I am in (and blogging about) the Septuagint, this makes me happy to see. The NETS is far from a perfect translation, but it’s the best English translation on the market right now.

In the middle you can see I have the Greek of Genesis 1 open, with the NETS right next to it and the IVP New Bible Commentary on the right of the middle section.

Then in the top right corner I opened the LEH Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint, available in previous Accordance versions only as a paid, add-on module (from what I understand). The bottom right corner shows the Hebrew text of Genesis 1.

Each of these boxes/windows are changeable and rearrangeable. I look forward to spending more time exploring the various configurations available to me through Accordance.

In sum: A quick, easy install with just that one hiccup of a missing module–soon to be resolved with a released fix, I’m sure. (UPDATE 8/23/12: It’s fixed!) And the layout and its flexibility has really impressed me on first use.

And, oh. The interface? Absolutely stellar. I love seeing a high-powered Biblical languages-oriented program native to a Mac. The interface in Accordance is as smooth as any program I’ve ever seen from Apple.

So far, so good.

UPDATE: Parts 2 and 3 of my review are here and here.

UPDATE 2: Here is part 4, a review of the Original Languages Collection.

UPDATE 3: Here is part 5, “Bells and Whistles.” UPDATE 4: part 6, “More Bells and Whistles.”