When I preached through Jonah last Advent, I knew the JPS Commentary on Jonah would be helpful. What I wasn’t expecting was how often I would eagerly turn to Kevin J. Youngblood’s new Jonah volume in the recently begun Hearing the Message of Scripture commentary series. It might be the best commentary (in this reviewer’s humble opinion) written on Jonah.

Format of the Commentary

Each passage of Jonah includes the following sections:

- Main Idea of the Passage–a short, couple-sentence overview, where Youngblood helps you get oriented to the text.

- Literary Context–The author shows how the passage under consideration ties in with the rest of the book.

- Translation and Outline–the author’s original translation and visual layout of the biblical text.

- Structure and Literary Form–this looks at literary features and the rhetorical aims of Jonah. This section is especially strong.

- Explanation of the Text–the primary section of each passage, comprising the verse-by-verse commentary proper.

- Canonical and Practical Significance–though Youngblood is plenty practical throughout, this section is especially helpful for preachers, teachers, or any Bible reader wanting to know how to apply the message of the text.

For example, here is Youngblood on the main idea of Jonah 4:1-4:

He then situates the passage in its larger context:

From there he relates Jonah 4:1-4 to the patterns of the rest of the book (“Every encounter with Gentiles brings Jonah to a crisis point”), surmises why Jonah wants to die (“Jonah cannot see how YHWH could simultaneously maintain his covenant faithfulness to Israel and grant clemency to Nineveh”), explains the text in detail, and then relates it to Moses and the other prophets and their interactions with “the nations.”

Youngblood’s Insights Make the Text Come Even More Alive

Youngblood makes the literary features of the text come alive. Regarding Jonah’s short stint in the belly of a fish, Youngblood writes:

The fish, however, functions as a means of deliverance and transportation from the murky depths back to the orderly realm of dry land. In this respect, the fish is the antithesis of the ship, which carried Jonah from the orderly realm of dry land out to the chaotic deadly sea.

Correspondingly, Jonah’s disposition and activity in the fish is the antithesis of his disposition and activity on the ship. Whereas Jonah pays out of his own pocket for passage on the ship, the journey in the fish back to land and life is free, courtesy of YHWH.

He continues to unpack the “important contrast” between ship and fish to help the readers with “the peak episode of the book’s first main section.”

This sort of analysis and clear explanation is emblematic of what the reader will find in every section of the book.

Final Evaluation: Easily a Top 3 Jonah Commentary

And what’s not to love about the first paragraph of the Introduction mentioning a Bruce Springsteen song? Here it is, by the way:

To write a nearly 200-page commentary with a 20-page introduction on a 4-chapter book of the Bible is no small feat; and none of what’s here is fluff. Youngblood notes in his introduction: “An understanding of three overlapping contexts–canonical, historical, and literary–is critical to the book’s interpretation.” He helps the reader attain ample understanding of those contexts and more.

Youngblood says only that this volume “strives to advance the discussion regarding Jonah’s message.” I think it does far more. This is easily a top 3 Jonah commentary–maybe even the best one I’ve used.

You can read a .pdf sample of the commentary here. See also my review of Obadiah in the same series.

I am grateful to Zondervan for the gratis review copy of this commentary, which was offered for an unbiased review. You can find the book on Amazon here. The Zondervan product page is here.

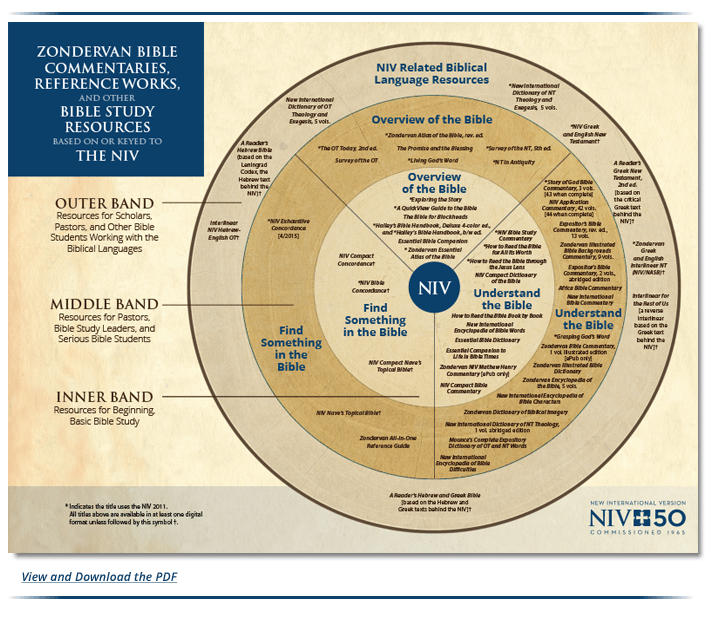

As with the Revised EBC volume, the introduction to Psalms Volume 1 in the NIV Application Commentary series (NIVAC) covers good ground: authorship, historical use of Psalms (in temple worship, as well as the move “from public performance to private piety”), poetic conventions, Hebrew poetry specifically (parallelism, use of refrains, acrostics), Psalm headings, and types of Psalms.

As with the Revised EBC volume, the introduction to Psalms Volume 1 in the NIV Application Commentary series (NIVAC) covers good ground: authorship, historical use of Psalms (in temple worship, as well as the move “from public performance to private piety”), poetic conventions, Hebrew poetry specifically (parallelism, use of refrains, acrostics), Psalm headings, and types of Psalms.