This textbook is a great one. I’m amazed at how much Aramaic it helped me pick up in just a long afternoon and evening. What follows is my review of Miles V. Van Pelt’s stellar text, Basics of Biblical Aramaic. It’s a winner!

Basics of Biblical Aramaic (BBA hereafter) is a “Complete Grammar, Lexicon, and Annotated Text.” I’ll review each of these components in turn.

Scope, Aim and Audience

BBA seeks to include “everything you need to learn biblical Aramaic” and is “designed for those who already have a working knowledge of biblical Hebrew.” This is a fair expectation, since most students of Aramaic only come to Aramaic having already had Hebrew (and often Greek, too). This allows Van Pelt to use Hebrew as a springboard for Aramaic throughout the book, which he does to great effect. He writes “for those students who desire to study, teach, and preach faithfully from those portions of the Bible that appear in Aramaic.”

I write as a member of Van Pelt’s target audience. I’ve had (more than) a year of Hebrew but no Aramaic to date.

Grammar

Van Pelt divides the grammar into the following sections:

- Phonology, in which he introduces the Aramaic alphabet, vowels, and syllabification

- The Nominal System, in which he covers nouns (absolute, determined, and construct states), conjunctions, prepositions, pronouns and pronominal suffixes, adjectives, numerals, adverbs, and particles

- The Verbal system, in which he covers the simple Peal stem in all its conjugations (perfect, imperfect, imperative, etc.), followed by the derived stems in their multiple conjugations

- Six pages of quick-reference Charts and Paradigms

Here is a sample pdf of the Table of Contents and first few chapters. In the book’s layout and in many other ways, BBA is like Van Pelt’s Basics of Biblical Hebrew (BBH), which he co-authored with Gary D. Pratico.

As with BBH the typical chapter layout of BBA is grammar followed by vocabulary. And in this case, since the workbook is essentially included in the text, chapters close with exercises. There is no answer key included, but the book lists the site from which it can be downloaded.

Van Pelt classifies verbs according to the “Peal” stem and its derived stems–also explaining alternate verbal terminology (G-stem, etc.). As he explains the various conjugations, he keeps aspect firmly in mind:

The incomplete (or imperfective) aspect of the Imperfect conjugation is well suited for describing present and future actions and so a present or future tense English translation is common with this verbal form. However, it is important to remember that that imperfective aspect of the imperfect conjugation may refer to actions in the past, present, or future….

One of Van Pelt’s aims in this textbook is “pedagogical sensitivity,” which he notes has not always appeared in Aramaic grammars. (He may have this one by Alger F. Johns in mind, which, good as it is, is not as user-friendly.) He succeeds immensely in this regard. That Van Pelt is a professor in an actual classroom is on display throughout the text; his tone is warm and even encouraging in many places. Each chapter concludes with a “Before You Move On” section, which helps the reader distinguish between things he or she needs to commit to memory and what he or she can leave for future reference.

Van Pelt’s grouping of vocabulary also exhibits “pedagogical sensitivity.” Initial lists have vocabulary that is similar or identical to Hebrew, so that an Aramaic student can get a quick jump on vocabulary acquisition. Van Pelt groups several lists according to semantic domain and also parts of speech. This is merciful to the students who will work their way through BBA (and good pedagogy). He includes all Aramaic words occurring four times or more in the OT, which constitute 91% of the text.

Lexicon

The lexicon is a comprehensive one that includes every Aramaic word occurring in the OT. Van Pelt bases the definitions/glosses on HALOT. There are definitions for different stems of each verb, too. There are no word frequency counts, either here or in the vocabulary lists. (Basics of Biblical Hebrew has frequencies in the vocab lists at the end of each chapter, one of its great features.) However, this may not be as essential as in Hebrew, since the Aramaic corpus in the OT is smaller. Van Pelt does include frequency statistics for many prepositions, conjunctions, adverbs, particles, and stems as he introduces them throughout the text.

Annotated Text

This is the best feature of an already great textbook. In the same way that Van Pelt and Pratico’s Graded Reader of Biblical Hebrew helps the student to really dig into the text, the Annotated Text in the back of BBA allows the student to put his or her new knowledge of Aramaic into practice. Every OT verse and passage in Aramaic is included: Genesis 31:47, Jeremiah 10:11, Daniel 2:4b-7:28, Ezra 4:8-6:18, and Ezra 7:12-26. The footnotes link back to specific chapters and sections of the text, and Van Pelt includes detailed morphological and lexical analysis of various words.

Further reflections

I have only two (minor) critiques of this textbook, which are as much as anything hopes for small adjustments that might be made in a future printing or edition of this book.

First, there is little about Aramaic in its Northwest Semitic context. This isn’t an oversight; Van Pelt says his grammar is not “written for Aramaic scholars or for students interested in comparative Semitic grammar.” Instead he wants to help produce a “working knowledge” for those who will “study, teach, and preach faithfully” from the Aramaic portions of the Bible. Fair enough. And he does allude to further discussions of Aramaic as a language in his footnotes. But as I imagine myself teaching and preaching Aramaic portions of the Bible, I think it would be helpful to know something of Aramaic’s context and development, to explain to my congregation. This could simply be a few paragraphs in a future edition.

Second, the verbal diagnostics Van Pelt highlights (using “the identification of distinctive verbal features unique to a group of related verbal forms”) are explained in the individual chapters, but not color-coded in the paradigm charts. They are given in red in the Hebrew textbook Van Pelt co-authored, and this was one of the most useful parts of that book–it really aided in learning the paradigms. Van Pelt does explain what diagnostics to look for, but I’d love if a future edition or printing could color-code the vowels/consonants that constitute the various verbal diagnostics. (UPDATE: I had thought that perhaps the lack of color in verbal diagnostics was a print cost issue. I’ve now been able to confirm that there will eventually be an electronic release of the grammar with color.)

Also, though this might be asking a lot of a single text, I found the English to Hebrew composition exercises in the BBH workbook to be a great way to improve my Hebrew. Perhaps supplemental composition exercises could find their way onto Van Pelt’s site in the future?

I initially thought a $45 retail price was steep for a paperback. But considering that this includes a grammar text, workbook exercises, a comprehensive Aramaic lexicon, and an annotated text of all the Aramaic in the Old Testament… it’s actually reasonable. In the Hebrew and Greek equivalents to this textbook, the text, workbook, and set of annotated readings are all separate volumes. This was a good move on the book’s part, I thought, and makes it easy to refer to it time and again as a one-stop shop for Aramaic acquisition and development.

What stands out most to me about Basics of Biblical Aramaic is the very-nice-to-have Annotated Text at the back with all the Aramaic OT passages. And another standout feature of this text is that Van Pelt truly does display “pedagogical sensitivity” throughout the text. Who would have thought an Aramaic textbook could have such a conversational tone without sacrificing thoroughness and good pedagogy?

Five stars. I imagine this textbook will become the standard in seminary and upper-level college courses where students learn biblical Aramaic.

My thanks to Zondervan for the review copy of this textbook. Find it here on Powell’s or here at Zondervan’s product page.

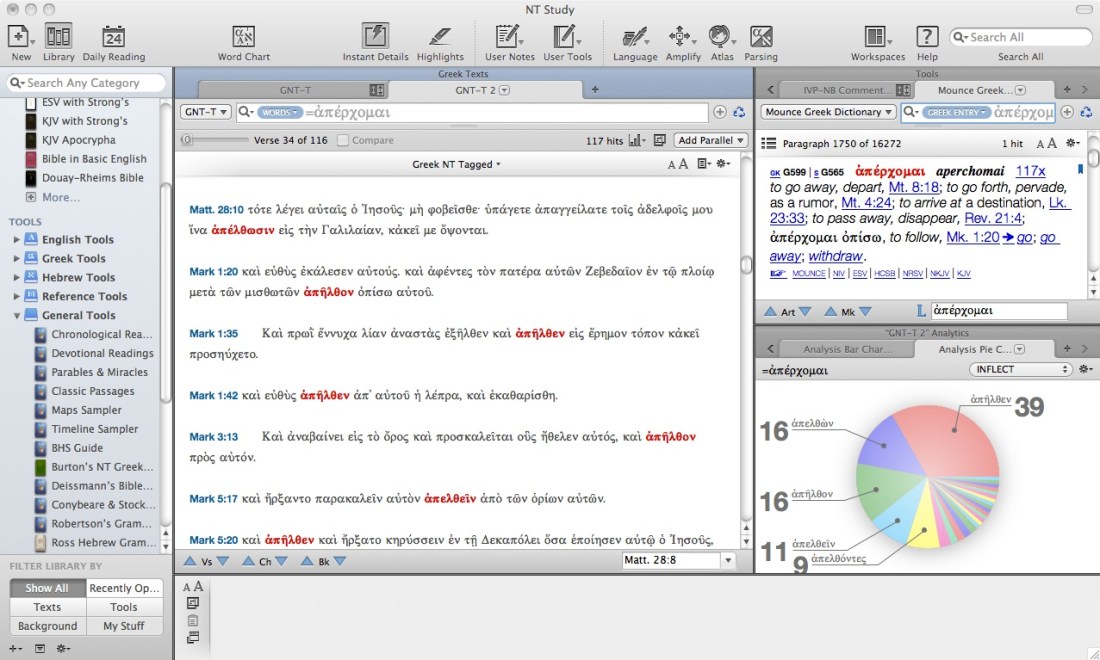

I recently read somewhere in the Accordance Forums that an early Accordance user from the 1990s said the product should come with a warning that it may cause sleepless nights! As I’ve reviewed Accordance 10 (as a long-time Mac user but new Accordance user), I’ve already seen the wisdom in that suggestion. It’s hard to put down. Accordance is actually a really fun program to use: sleek, pleasing, productive, and really easy to customize as I’ve gotten the hang of how to move things around.

I recently read somewhere in the Accordance Forums that an early Accordance user from the 1990s said the product should come with a warning that it may cause sleepless nights! As I’ve reviewed Accordance 10 (as a long-time Mac user but new Accordance user), I’ve already seen the wisdom in that suggestion. It’s hard to put down. Accordance is actually a really fun program to use: sleek, pleasing, productive, and really easy to customize as I’ve gotten the hang of how to move things around.

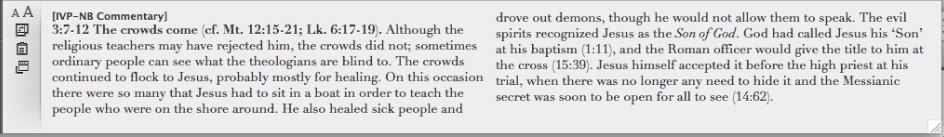

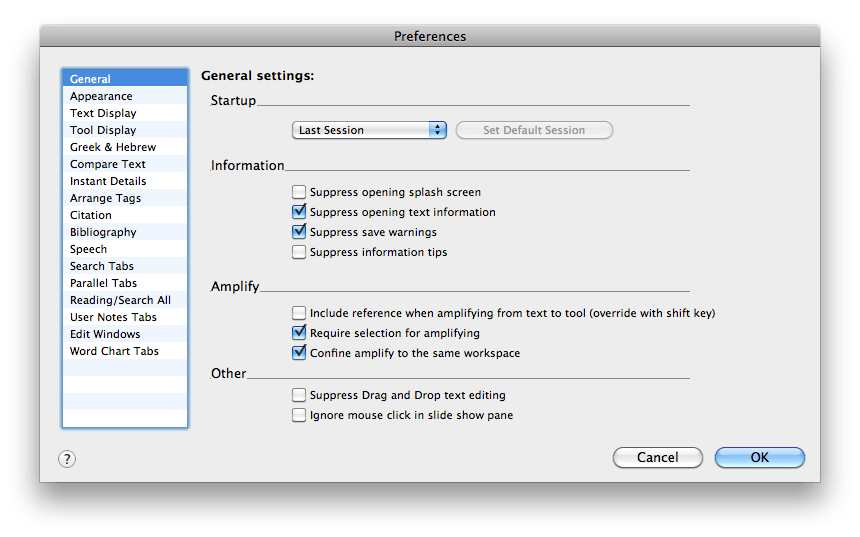

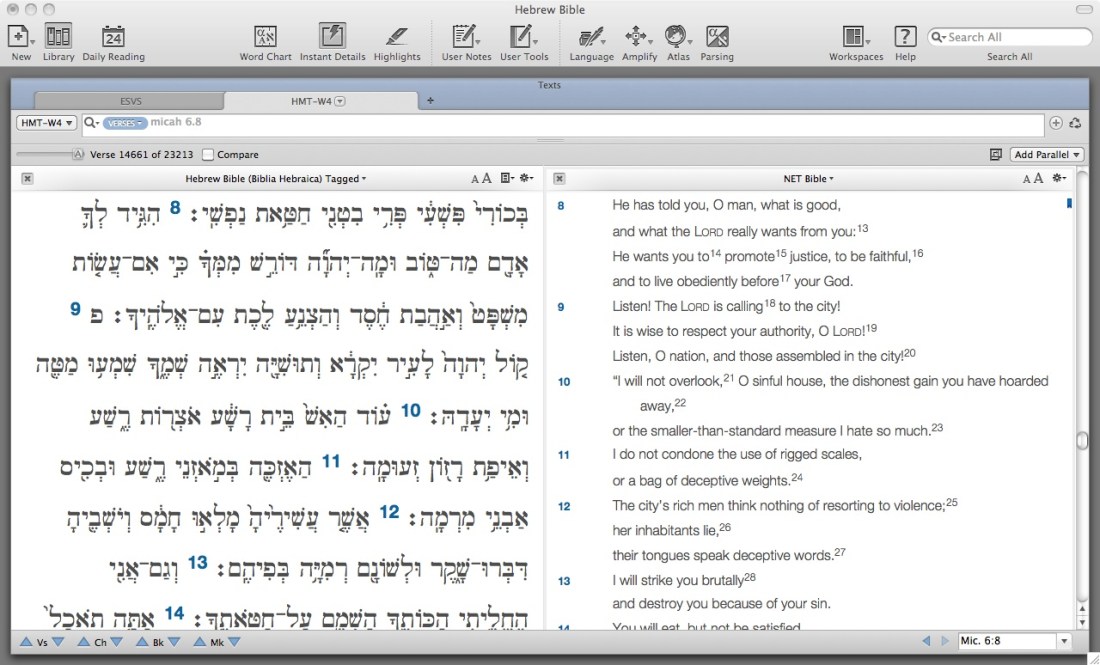

Having been trained at a seminary that prizes original languages, I am a little biased against interlinears for those who are really seeking to learn the language. (I find the “burn your interlinear” mantra I’ve heard from some quarters a little excessive, though.) Realistically, however, some exposure to biblical languages is better than none, and there are surely users who will want to make use of an interlinear. Greek and Hebrew texts come with interlinear English translation and word parsing as the default, but you can easily turn it off and back on again as needed. See the options at left, where you can set up exactly what you want to show in your interlinear. Here’s what the interlinear feature looks like with the options at left checked (click for larger):

Having been trained at a seminary that prizes original languages, I am a little biased against interlinears for those who are really seeking to learn the language. (I find the “burn your interlinear” mantra I’ve heard from some quarters a little excessive, though.) Realistically, however, some exposure to biblical languages is better than none, and there are surely users who will want to make use of an interlinear. Greek and Hebrew texts come with interlinear English translation and word parsing as the default, but you can easily turn it off and back on again as needed. See the options at left, where you can set up exactly what you want to show in your interlinear. Here’s what the interlinear feature looks like with the options at left checked (click for larger):