Oddly enough, the biggest challenge for me in my Hebrew exegesis classes was not to do with the Hebrew language itself. Instead, learning how to decipher the abbreviations and sigla in the “critical apparatus” of a scholarly Hebrew Bible stretched me most.

Oddly enough, the biggest challenge for me in my Hebrew exegesis classes was not to do with the Hebrew language itself. Instead, learning how to decipher the abbreviations and sigla in the “critical apparatus” of a scholarly Hebrew Bible stretched me most.

I recently wrote a brief introduction to the available scholarly editions of the Hebrew Jewish Scriptures (“Old Testament”), the Greek Jewish Scriptures (“Septuagint”), and the Greek New Testament, with most of the emphasis on that post falling on the Hebrew Bible:

Most students of the Hebrew Bible who read Hebrew know of the premier scholarly edition, the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS, here on Amazon). The BHS is now being updated by the BHQ (Q=Quinta), about which you can read more here. Both the BHS and BHQ are “diplomatic” editions of the text, which means that they reproduce a single “best” manuscript, the Leningrad Codex, in their cases. The footer in each page contains a critical apparatus, which lists variant readings from other manuscripts and versions that the editors have deemed to be of importance for getting even closer to the “original” (now often being called the “earliest attainable text”). In some cases, the editors may wish to show where another manuscript or version differs from the Leningrad Codex; the critical apparatus is where they do it.

However, the BHS editors show manuscript and version differences in their critical apparatus through the use of abbreviated Latin. Even those who know Latin will have to learn the abbreviations, and those who don’t know Latin will have an even harder time trying to decipher the apparatus.

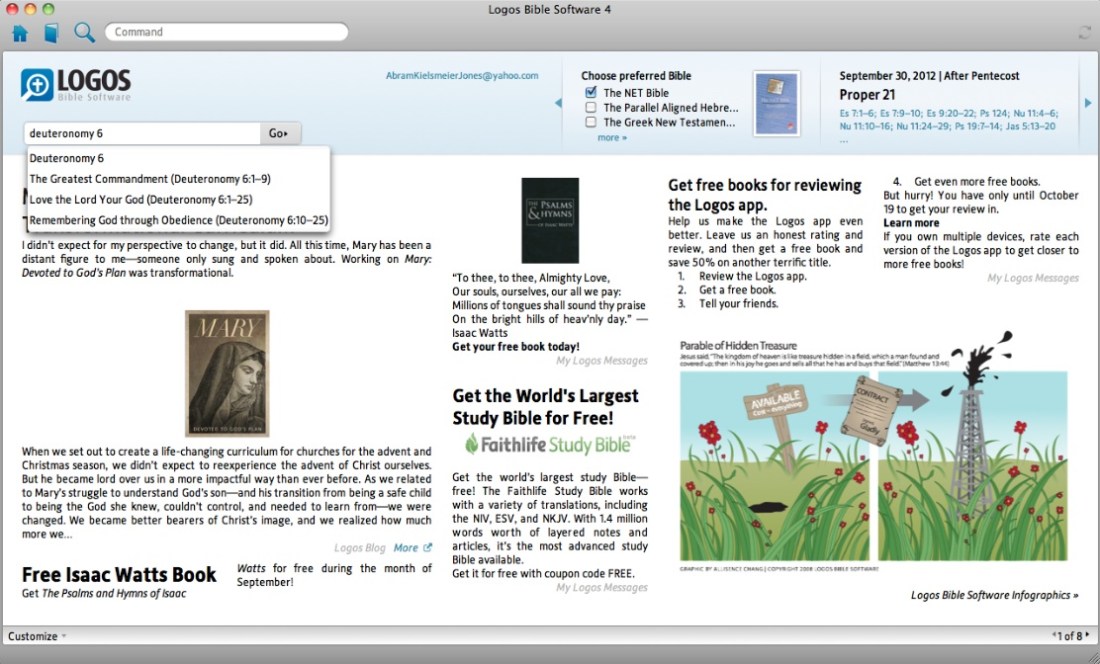

Having figured out my way around the print edition of the BHS, and having reviewed Accordance 10, I have been eager to use the BHS module in Accordance. Here I review it.

The Original Languages base package in Accordance comes with HMT-W4, which gives the user access to the Groves-Wheeler Westminster Hebrew Morphology 4.16. This text reflects additional and ongoing corrections to the Leningrad Codex. Accordance says HMT-W4 is “almost identical” to the BHS text.

But for the user who wants not just the text but the apparatus, an add-on module is needed. If you already have HMT-W4 or BHS-W4 for your Hebrew Bible in Accordance, you can save money and buy the apparatus by itself. It’s just $50, which is a good deal. (Note: there are no Masora–Masoretic marginalia–included in the module; it’s just the apparatus at the bottom of the page.) If you have Accordance and don’t already have a Hebrew text, you could buy this package, where BHS-T is the “complete text of the Hebrew Bible, following the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, with the Groves-Wheeler Westminster Hebrew Morphology 4.14. This module includes vowel pointing, cantillation marks, and lemma and grammatical tagging information for each word in the text.”

In any of these Hebrew texts in Accordance, there is instant parsing easily available as you go through the text.

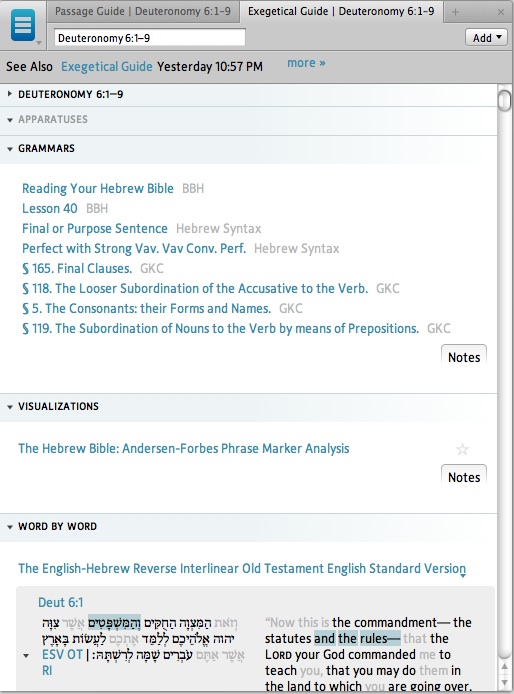

BHS with apparatus in Accordance significantly streamlines study and use of the critical apparatus. Accordance makes it easy to do textual criticism without carrying the heavy BHS around. I really appreciate being able to access the BHS critical apparatus on my laptop, and in a way that is integrated well into the Accordance program. The layout is good, the feel is intuitive, and the windows are easy to set up. Here’s how I have Accordance set up to use the critical apparatus with the Hebrew text and Old Greek in view (click to enlarge):

There’s the BHS critical apparatus, right under the text. Anything in blue in that window is hyperlinked and will display something in the Instant Details window. If I want to know what “pc Mss” means in the apparatus, I see it unabbreviated in the Instant Details just by mousing over the blue text. (If you don’t need the abbreviations expanded, you can also hover over the superscript letters in the BHS-T text, and the corresponding content from the apparatus pops up.)

Using the layout above you can quickly see what an abbreviation in the apparatus stands for in Latin, but this is not translated into English. In the above example, it’s obvious that “manuscripti” for “Mss” means manuscripts–no Latin knowledge is needed to understand that Latin word. But what is “pauci”? Those with good vocabulary may be able to recall that a paucity of something is a small number, a lack, so “pauci” here means few.

But not all Latin in the apparatus is that easy. I would like to have seen this module provide a translation from Latin into English. This is probably my only complaint about this module. I believe this is not unique to Accordance and has more to do with how the German Bible Society may have offered the licensing for the apparatus. All the same, getting from abbreviated Latin to unabbreviated Latin, while nice, may not be enough for the beginning text critic.

Some good news, though. There are two workarounds to be able to translate the apparatus contents from Latin to English. First, there is Google Translate, which I understand has improved its accuracy over the last few years. Here is the link for Google Translate from Latin to English. Simply copy Latin from Accordance into the query box in Google translate, and you’ll have your English. “prb l c” in the apparatus becomes, “probabiliter lege(ndum) cum” in Instant Details, which Google gives me as, “probably read with.”

A yet easier way to get to English is possible within Accordance itself, and it’s quite smooth, thanks to the good programming and easy layout of the software. Dr. Hans Peter Rüger’s well-known “English Key to the Latin Words, Abbreviations, and the Symbols of BIBLIA HEBRAICA STUTTGARTENSIA” is available in Accordance.

Note that in the bottom right zone, my far right tab (behind the open one) is this “BHS Latin Key.” I can easy look up an abbreviation in that tab’s search bar. It’s also simple to just right click the abbreviated word in the apparatus and “Look up” in “Dictionary” to quickly access the English/Latin key.

As far as the BHS apparatus itself, BHS remains the scholarly standard. BHQ is beginning to update/replace it, and there are other scholarly projects underway. The BHS apparatus is not exhaustive, nor could it be. But it does offer a good representation of variant readings from different versions (e.g., the Latin Vulgate, the Greek LXX, the Syriac Peshitta, Aramaic Targums, etc.) and different manuscripts (whether a specific Old Greek manuscript or just the general “Mss” for “manuscripts”).

There are different editors for different portions of the BHS, and some are less cautious than others in suggesting textual emendations. In the Minor Prophets, for example, editor Karl Elliger seems to have no trouble writing “prp”=”propositum”=”it has been proposed” when he wants to suggest an alternate reading. Sometimes this means that someone else has proposed what Elliger is footnoting; other times it’s just his suggestion, and not always with textual/manuscript evidence accompanying the suggestion. So the user of BHS should not use the critical apparatus, well… uncritically.

An especially neat feature that wowed me is that I can open up the apparatus and search by content to study all 2,146 times the Latin abbreviation “prp” occurs in the BHS apparatus. You can even search the apparatus for its Hebrew and Greek contents. Curious how often ποῦ finds its way into the apparatus? A simple search shows its four occurrences.

And you can search the apparatus by manuscripts mentioned. Change the search bar to “manuscripts,” then right click in the bar and select “Enter Word…” and you get this:

It’s a great way to be able to interact with the apparatus, much of which simply isn’t possible in print.

Bonus: Accordance offers an excellent, succinct explanation of critical editions here, with emphasis on the critical editions available in Accordance. If you’re interested in BHS in Accordance, you’ll want to read it.

If you do text criticism in the Hebrew Bible and have the money to spare, Accordance’s BHS apparatus is well worth getting, though most users will want to make sure they also have the “BHS Latin Key,” too. All in all, it’s a well-executed and seamlessly-integrated module.

Thank you to Accordance for providing me with a copy of the BHS and BHQ modules for review. See all the parts of my Accordance 10 review (including the Beale/Carson commentary module) here. I will review the BHQ separately in the future.