In the past when I’ve preached on Ephesians 2:1-10, I’ve gone straight for the gold of Ephesians 2:8-10:

For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast. For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do.

The first seven verses have just felt like an opening band that–while good–wasn’t necessarily what I had come to see.

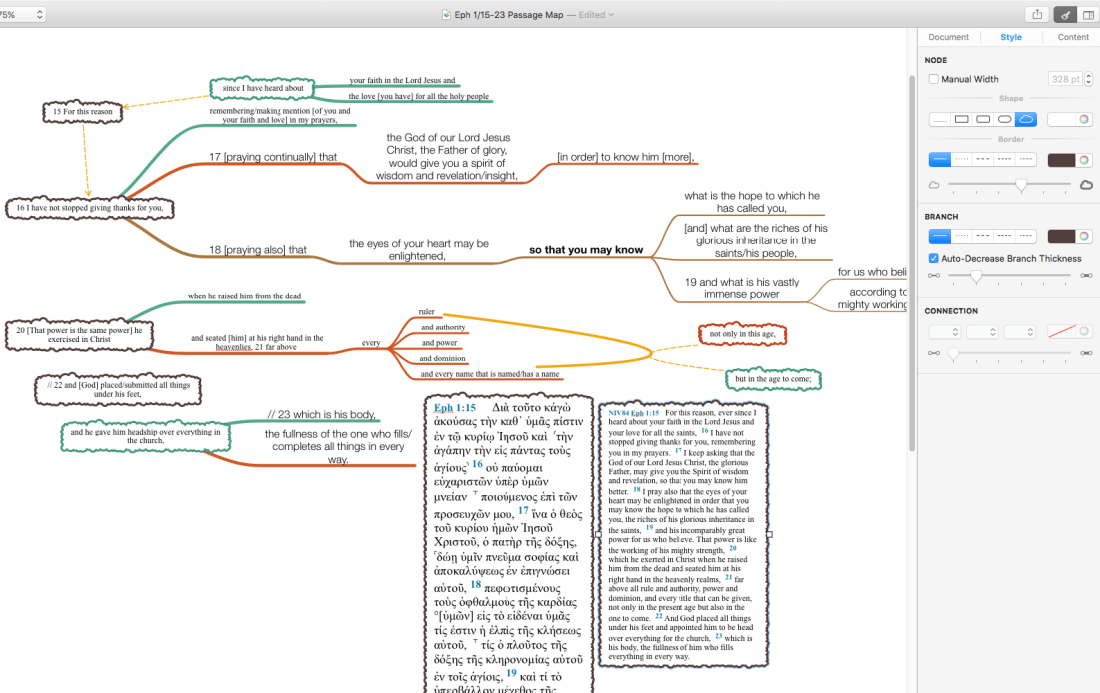

I see the passage differently now, having spent a good deal of time trying to understand Paul’s flow.

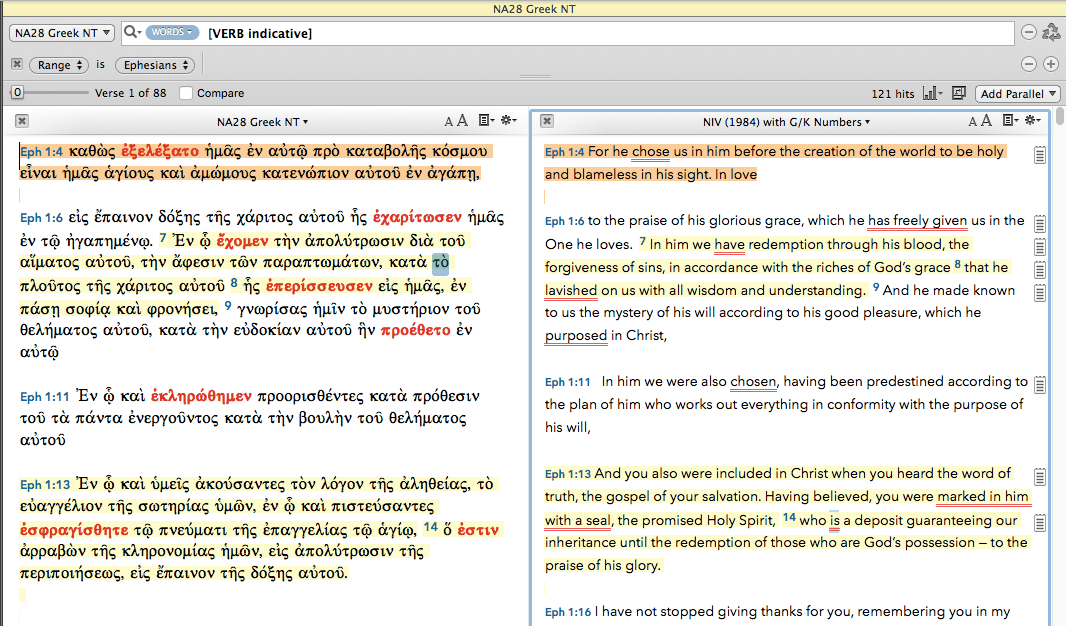

Here’s the passage from the 1984 NIV, followed by the passage in Greek:

Eph 2:1 As for you, you were dead in your transgressions and sins, 2 in which you used to live when you followed the ways of this world and of the ruler of the kingdom of the air, the spirit who is now at work in those who are disobedient. 3 All of us also lived among them at one time, gratifying the cravings of our sinful nature and following its desires and thoughts. Like the rest, we were by nature objects of wrath. 4 But because of his great love for us, God, who is rich in mercy, 5 made us alive with Christ even when we were dead in transgressions—it is by grace you have been saved. 6 And God raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms in Christ Jesus, 7 in order that in the coming ages he might show the incomparable riches of his grace, expressed in his kindness to us in Christ Jesus. 8 For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this not from yourselves, it is the gift of God— 9 not by works, so that no one can boast. 10 For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do.

Eph 2:1 Καὶ ὑμᾶς ὄντας νεκροὺς τοῖς παραπτώμασιν καὶ ταῖς ἁμαρτίαις ὑμῶν, 2 ἐν αἷς ποτε περιεπατήσατε κατὰ τὸν αἰῶνα τοῦ κόσμου τούτου, κατὰ τὸν ἄρχοντα τῆς ἐξουσίας τοῦ ἀέρος, τοῦ πνεύματος τοῦ νῦν ἐνεργοῦντος ἐν τοῖς υἱοῖς τῆς ἀπειθείας· 3 ἐν οἷς καὶ ἡμεῖς πάντες ἀνεστράφημέν ποτε ἐν ταῖς ἐπιθυμίαις τῆς σαρκὸς ἡμῶν ποιοῦντες τὰ θελήματα τῆς σαρκὸς καὶ τῶν διανοιῶν, καὶ ἤμεθα τέκνα φύσει ὀργῆς ὡς καὶ οἱ λοιποί· 4 ὁ δὲ θεὸς πλούσιος ὢν ἐν ἐλέει, διὰ τὴν πολλὴν ἀγάπην αὐτοῦ ἣν ἠγάπησεν ἡμᾶς, 5 καὶ ὄντας ἡμᾶς νεκροὺς τοῖς παραπτώμασιν συνεζωοποίησεν τῷ Χριστῷ, _ χάριτί ἐστε σεσῳσμένοι _ 6 καὶ συνήγειρεν καὶ συνεκάθισεν ἐν τοῖς ἐπουρανίοις ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ, 7 ἵνα ἐνδείξηται ἐν τοῖς αἰῶσιν τοῖς ἐπερχομένοις τὸ ὑπερβάλλον πλοῦτος τῆς χάριτος αὐτοῦ ἐν χρηστότητι ἐφ᾿ ἡμᾶς ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ. 8 Τῇ γὰρ χάριτί ἐστε σεσῳσμένοι διὰ πίστεως· καὶ τοῦτο οὐκ ἐξ ὑμῶν, θεοῦ τὸ δῶρον· 9 οὐκ ἐξ ἔργων, ἵνα μή τις καυχήσηται. 10 αὐτοῦ γάρ ἐσμεν ποίημα, κτισθέντες ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ ἐπὶ ἔργοις ἀγαθοῖς οἷς προητοίμασεν ὁ θεὸς, ἵνα ἐν αὐτοῖς περιπατήσωμεν.

Assuming 2:1 is the beginning of a new sentence (Καὶ ὑμᾶς ὄντας νεκροὺς τοῖς παραπτώμασιν καὶ ταῖς ἁμαρτίαις ὑμῶν), there is not a clear indicative verb in a non-subordinate clause really anywhere in sight, at least not until an indicative verb of ἤμεθα (“we were”) in 2:3 (και ἤμεθα τέκνα φύσει ὀργῆς ὡς καὶ οἱ λοιποί). (Though I confess I’m not sure why this is preceded by καὶ if it’s not a participle.)

So 2:3’s ἤμεθα is the first indicative verb in the whole passage not in a subordinate clause. 2:1 (“You, being dead…”=participle) leads to 2:3b’s “we were children of wrath” (and notice Paul’s subtle shift in 2:3a from “you” as sinner to “we” as sinners). This wrath is the outcome one would anticipate.

Then there is a construction with a participle in 2:4a, similar to how the chapter began: ὁ δὲ θεὸς πλούσιος ὢν ἐν ἐλέει–“God, being rich in mercy”=participle. This is a grammatical (and theological) balance to “you, being dead.”

Paul is about to expand on this nice contrast, but first he interrupts with this recapitulation in Ephesians 2:5a: καὶ ὄντας ἡμᾶς νεκροὺς τοῖς παραπτώμασιν (and you, being dead in transgressions). It is nearly identical wording to how the passage started, forming an inclusio with 2:1. (Just in case we missed it the first time, that we were dead in sin!)

Now there is the continuation of θεὸς ὢν–completed with a main verb to grammatically match but theologically and narratively replace the “we were children of wrath.” It is the high point of the passage, the phrase that holds the whole passage together. It has the three main verbs the listener/reader will have been waiting for since the participle of 2:1.

συνεζωοποίησεν τῷ Χριστῷ

God made us alive in Christ!

Then the rest of the passage is the unfolding (2:6 gives two more main verbs: he raised us and seated us with Christ) and purpose (2:7) and reiteration with implications (2:8-9) of συνεζωοποίησεν τῷ Χριστῷ.

I take 2:10 and its ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ, then, to be the “application” section of this passage.

Interestingly enough, read this way, the ever-popular 2:8-9 are not the main point of the passage, at least not on their own. They need to be understood in light of God’s specific actions of making us alive in Christ (συνεζωοποίησεν τῷ Χριστῷ), raising us (συνήγειρεν) and seating us in the heavenly realms in Christ (συνεκάθισεν ἐν τοῖς ἐπουρανίοις ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ).

The technical commentaries confirm this way of reading the passage, namely, that the structural and grammatical center is 2:5-6, describing the three-fold action of God in making us alive, raising us, and seating us.

It’s a nuance, to be sure, and it doesn’t take away from the power of 2:8-10. But it does mean my preaching focus tomorrow will be on the three-fold action of God, and how we understand that as his saving grace, to be received by faith.