The Art & Craft of Biblical Preaching (Zondervan, 2005) is a massive and indispensable reference work for preachers. It is true to its sub-title: A Comprehensive Resource for Today’s Communicators. When it comes to the process of preaching–start to finish–there is very little the book does not cover. Virtually all aspects of sermon preparation and delivery are here, such as the call of the preacher (chapter 1), careful consideration of the listeners (chapter 3), sermon structure (chapter 5), delivery (chapter 8), and seeking sermon feedback (chapter 11).

The book’s 201 (!) chapters vary in length. A handful of the articles are barely a page, while others approach ten pages. Not that length correlates with quality. One of the most beneficial articles is the one-page set of self-evaluation questions by Haddon Robinson (“A Comprehensive Check-Up,” 701).

The quality of article is high, with just a few exceptions along the way–perhaps inevitable among over 100 contributors. (A handful of articles feel more vague than I would have hoped.) There is also an overwhelmingly disproportionate inclusion of male contributors, while there are just a few articles from female contributors, and no women on the book’s accompanying 14-track sermon audio CD. The CD is otherwise a great inclusion, since you get to hear great preaching examples in action. My five-year-old loved the first few stories on the disc.

The Art & Craft is a joy to read and a goldmine of a resource. Following are three highlights of the rich book, as well as some reflections on how they have informed my preaching.

1. Preaching with Intensity

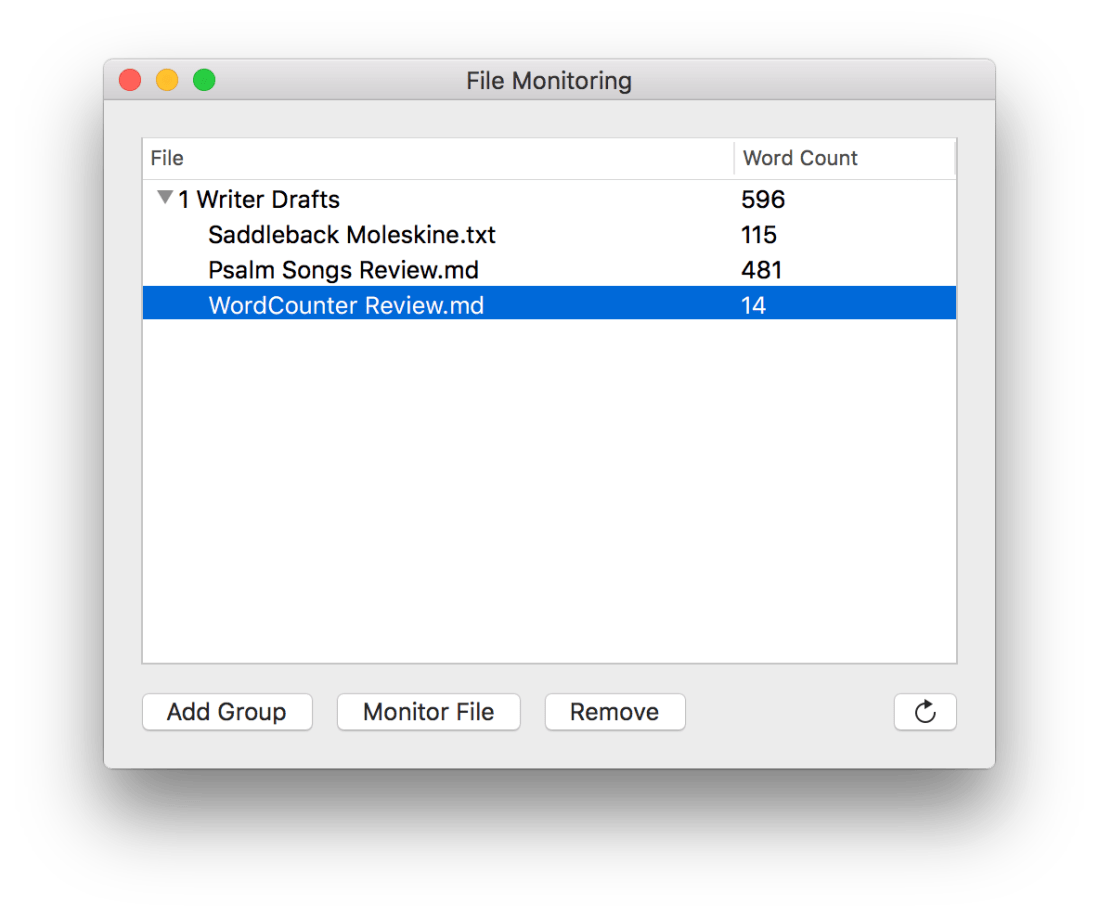

“Preaching with Intensity” (596), by my friend Kevin A. Miller, is one of the best essays in the book. I first read the article two years ago, and only realized when re-reading it recently how much of Miller’s advice I’ve internalized. It’s that good.

He leads off by asking, “Why is it that sometimes we as preachers feel a message so deeply, yet our listeners don’t feel that? Why is something that’s so intensely meaningful to us not always communicated in a way that grips the congregation as intensely?” (596) He suggests four factors as to “why intensity doesn’t transfer.” One of these is “the time factor,” and Miller’s point hit me so hard the first time that I’ve never forgotten it. (That’s a rare occurrence for me.)

By the time I step into the pulpit, I have studied for this message all week. I meditated on the text. I read commentaries. I prayed about the message. I gave this sermon from eight to twenty hours of my best thought, prayer and energy.

Amen! say the preachers! But here’s the blunt truth:

But the people listening to me are hearing the sermon cold. What’s become so meaningful to me has had no time to sink in to them. I can’t expect the truths that have gripped me during hours of study to automatically grip a congregation–unless I practice the skills I describe below.

Once you pick up this book, turn to page 597 to pick it up from here. Miller will walk you through what to do next.

Because of “the time factor,” one of my first steps in preaching prep (on my better weeks!) is reading through the text out loud in English, since that is what will happen immediately before the sermon in the actual church service. With note-taking capability ready at hand, I try to anticipate what questions and reactions might come up when the congregation hears it Sunday–that is what will be top of mind for them (not my hours of study!) as soon as I begin the sermon. It’s not that I need to try to come up with FAQ For Sunday-Morning Hearers of This Passage to start off every sermon, but keeping the congregation in mind like this has become an essential part of my process.

One more takeaway from Kevin Miller, since it’s stuck with me: don’t over-nuance your points. I was a philosophy major, and I have an educated congregation, so this is difficult for me. Miller doesn’t mean don’t be nuanced–our faith requires it at times. He just means:

Every nuance and qualifier, though it may add technical accuracy, also blunts the force of the statement we’re trying to make. Even if we believe something intensely, we can drain the energy out of our statement so that the congregation doesn’t sense that. It’s good to be accurate, to use nuance, to balance. But we must never let those good practices dull the share edge of the Bible’s two-edged sword. (598)

I’ve kept this advice close during my sermon editing process in recent months. Almost every draft revision includes taking out an overly (and probably unnecessarily) nuanced sentence or two.

2. Manuscript, Outline, or No Notes?

After my first 60 or so weekly sermons in the church I pastor, I remember moving from a 10-page manuscript to a 2-page outline. That entire fall I thoroughly enjoyed the flexibility of an outline, and found it enhanced my preaching, not made it worse (which I had feared). I swore off manuscripts forever.

The next spring, and ever since, I’ve been preaching from word-for-word manuscripts. (Ha!) Of course I add and delete and rephrase on the fly, once I look at the congregation and make connection with them. But I’m also thinking it’s time again for me to go back to using a more minimal outline.

Whether a preacher should write out her or his sermon, whether she should preach from an outline, or whether he should go into the pulpit with nothing but a Bible is a matter for the preacher to decide. It is, after all, a matter of style and personal preference.

In “No Notes, Lots of Notes, Brief Notes” (600), Jeffery Arthurs explores the benefits and drawbacks of each approach. I was pleasantly surprised by the nuance and balance offered, since Arthurs teaches at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, where the modus operandi is to require preaching with virtually no pulpit notes. Arthurs explores “no notes, lots of notes, and brief notes” (600). For each he asks, “Why Use This Method?”, “Why Avoid This Method?”, and, “How to Use This Method.”

The point I found most useful was under the “Lots of Notes” section. Two of the drawbacks to such an approach (as in my current practice of preaching from a manuscript) are, “Most readers cannot read with skill” (604) and, “Eye contact is difficult or impossible” (604). Those two points have not been challenges for me, but the third drawback has been an area of growth: “Most writers write in a written style” (604). Arthurs suggests preachers should write for the ear, and specifically gives tips to that end. “Your writing will seem redundant and choppy,” he says, “But that is how we talk” (605). So I’ve made efforts this year to preach with orality in mind.

3. The Value of Sermon Feedback

Since I’ve been soliciting preaching feedback from a few members recently, I was especially eager to read Part 11, Evaluation. Bill Hybels leads off with “Well-Focused Preaching” (687), one of the longer essays in the book. Hybels shares in detail how he looks for sermon evaluation, especially from his church’s elders. It’s a refreshingly honest essay. Hybels also helped me see again the connection between what the sermon is trying to do in relation to larger church goals and vision. This is a link that is too easy to forget when yet another Sunday message seems to be just around the corner.

William Willimon includes a questionnaire for sermon evaluation: “Getting the Feedback You Need” (698). I’m not sure I would use his numbers for rating a preacher’s sermon, though. To my mind there’s a subtle but important difference between sermon feedback and sermon evaluation. The book speaks in terms of sermon evaluation, but I prefer to use feedback when soliciting input from congregants. The sermon is not a performance to be graded or an initiative to be voted on by the congregation. Using the language of evaluation could easily put a congregant in a mindset of grading a sermon, which feels like a category mistake for something that is supposed to be formative. There may already exist among churchgoers the evaluation of, “I liked it” or, “I didn’t like it,” and asking for “evaluation” could unintentionally encourage that. Of course, preachers need feedback to know what’s connecting and not, and we can always improve in our proclamation of God’s Word. Either way I found benefit in the section on evaluation.

Haddon Robinson’s “Comprehensive Check-Up” (701) is short but sweet. He gives the preacher a host of good questions to ask herself or himself. There are questions especially for the introduction of the sermon (“Does the message get attention?”) and its conclusion (“Are there effective closing appeals or suggestions?”). There is a sense in which some of these questions read as common-sense measurements, but in the press of weekly ministry and preaching, it’s really to forget them. Robinson does preachers (and has done me) a great service by putting so many good self-evaluation questions in one place.

Barbara Brown Taylor offers a refreshing perspective in her “My Worst and Best Sermons Ever” (710). Her account of a sermon at the death of a baby girl is moving:

When it came time for the service, I walked into a full church with nothing but a half page of notes. I stood plucking the words out of thin air as they appeared before my eyes. Somehow, they worked. God consented to be present in them. (710)

She concludes–in a subtle corrective to the use of sermon “evaluation”–that there is value in being “reluctant to talk about ‘best’ and ‘worst’ sermons” (710). Indeed, “Something happens between the preacher’s lips and congregation’s ears that is beyond prediction or explanation” (710). The reader finishes her short piece wishing her writing had been featured more than in this and one other article.

Finally, “Lessons from Preaching Today Screeners” (704), features 10 questions “by which we evaluate all the sermons received by Preaching Today, and some of the lessons we’ve learned from listening” (704). It’s a fascinating read, and a set of questions to use in sharpening one’s own preaching. I was especially convicted by, “Is the sermon fresh?” There Lee Eclov cautions against preaching to the congregation “things they surely already know and believe, and doing so in terms the congregation would probably find overly familiar” (705). This one is a big challenge for me.

Conclusion

The Art & Craft of Biblical Preaching easily lends itself to both quick and sustained study. Whether you just pick it up and read what you need to give you a boost one week, or whether you spend hours poring over its advice, it’s an outstanding resource to keep at the desk or quick-access bookshelf. In “How to Use This Book,” the editors wisely say, “A manual like this–overflowing with helpful information–must be managed. …You will consciously focus on one important principle from a chapter for weeks or months. Eventually it will become second nature, and you will be ready to focus deliberate attention on another principle” (15).

As a production note, the book’s glued binding is an unfortunate choice for a rich reference book like this.

The editors are right in their expectation: “We expect this manual is one you will grow with for years to come” (15). I’m looking forward to my own continued growth as a preacher, and grateful to have this resource to help me to that end.

Here are all the main sections in the book, with the questions they set out to answer:

Part 1: The High Call of Preaching (“How can I be faithful to what God intends preaching to be and do?”)

Part 2: The Spiritual Life of the Preacher (“How should I attend to my soul so that I am spiritually prepared to preach?”)

Part 3: Considering Hearers (“How should my approach change depending on who is listening?”)

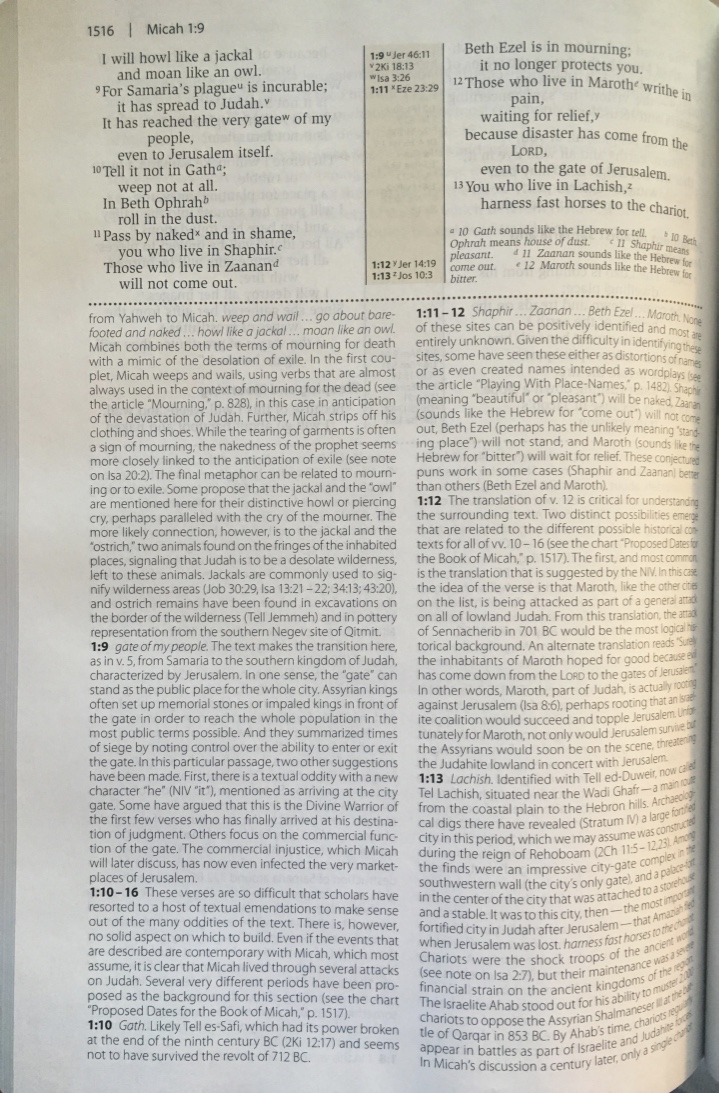

Part 4: Interpretation and Application (“How do I grasp the correct meaning of Scripture and show its relevance to my unique hearers?”)

Part 5: Structure (“How do I generate, organize, and support ideas in a way that is clear?”)

Part 6: Part and Style (“How can I use my personal strengths and various message types to their full biblical potential?”)

Part 7: Stories and Illustrations (“How do I find examples that are illuminating, credible, and compelling?”)

Part 8: Preparation (“How should I invest my limited study time so that I am ready to preach?”)

Part 9: Delivery (“How do I speak in a way that arrests hearers?”)

Part 10: Special Topics (“How do I speak on holidays and about tough topics in a way that is fresh and trustworthy?”)

Part 11: Evaluation (“How do I get the constructive feedback I need to keep growing?”)

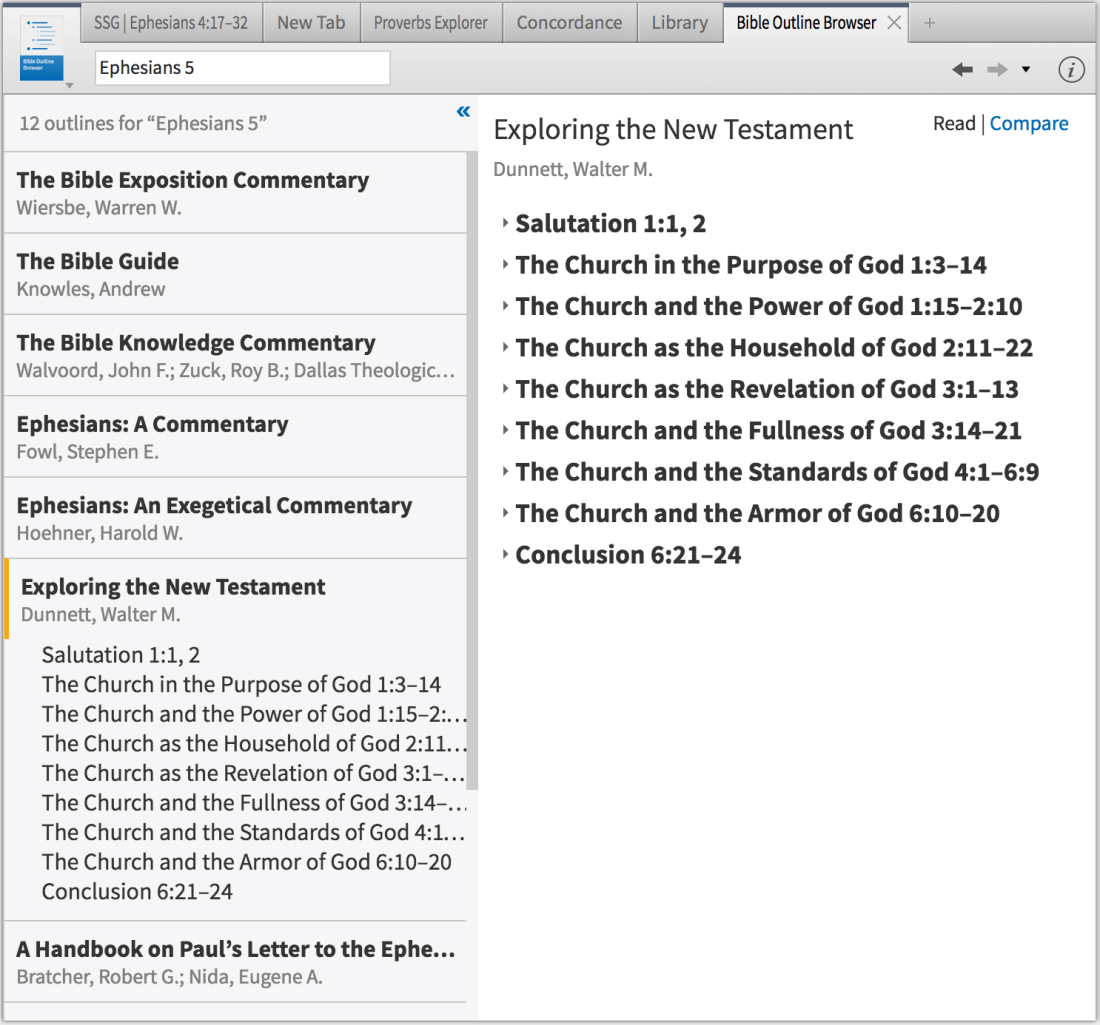

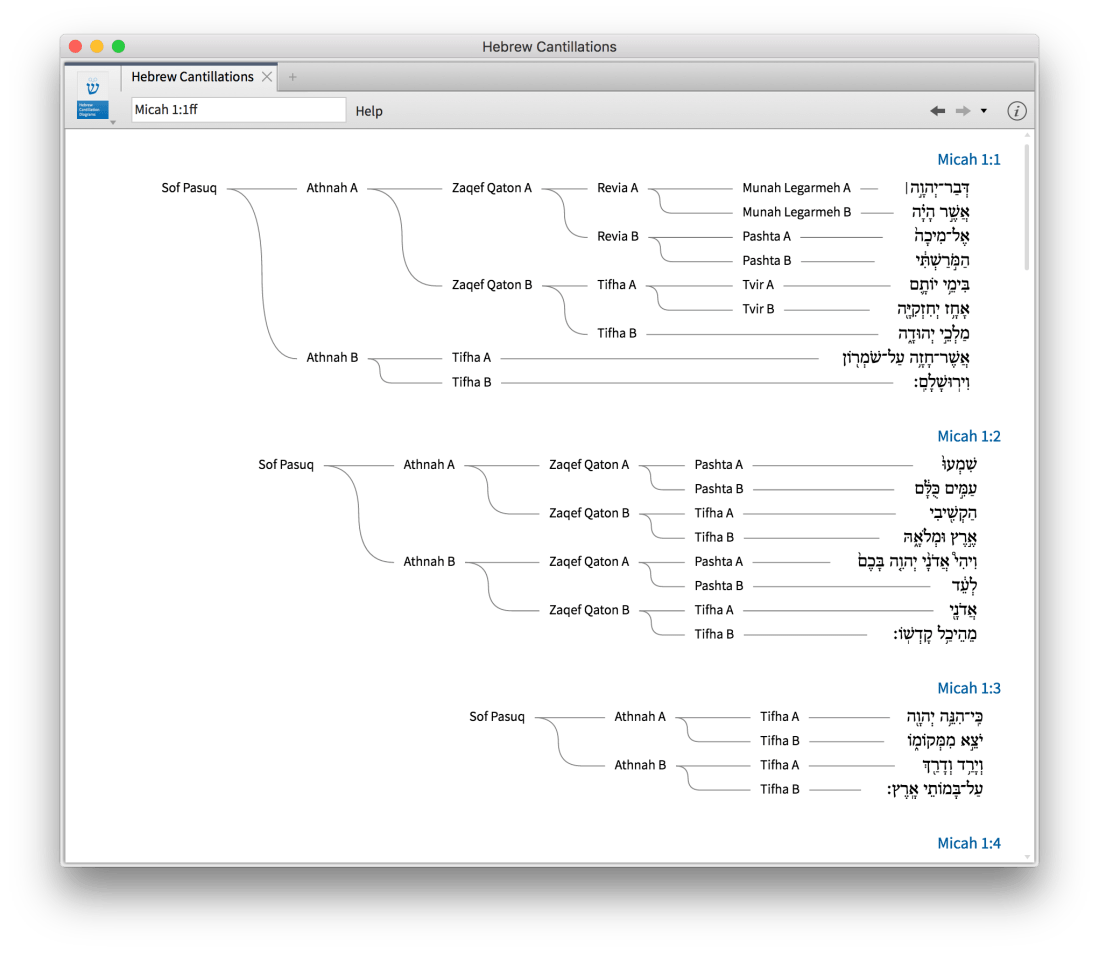

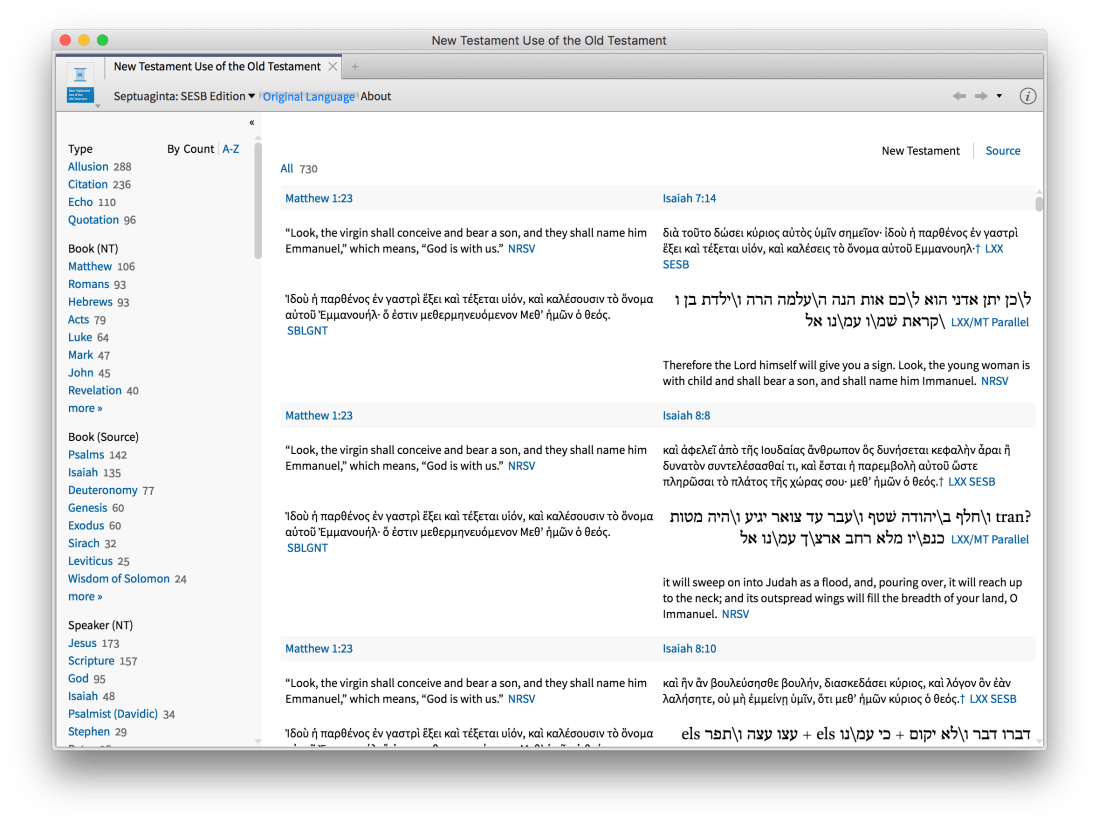

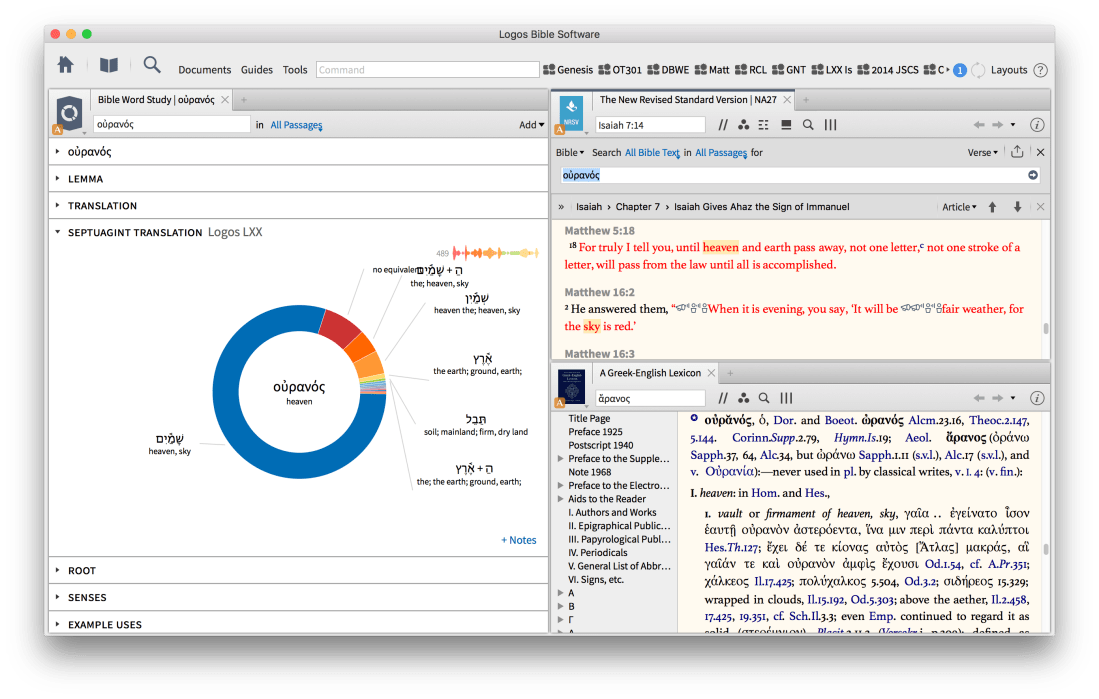

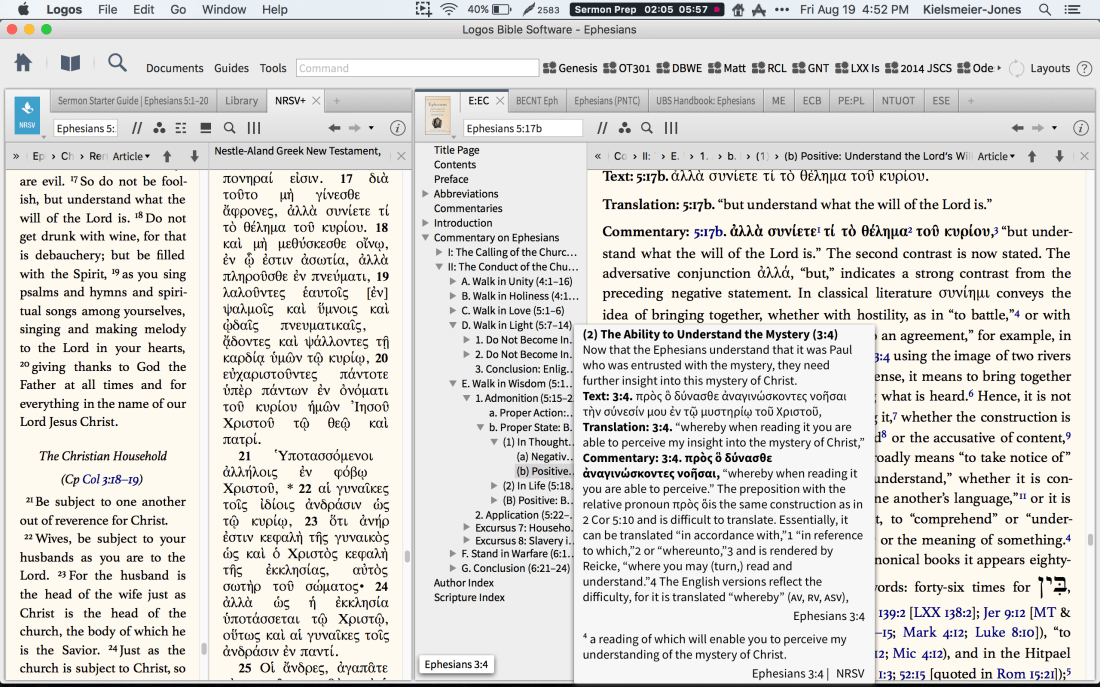

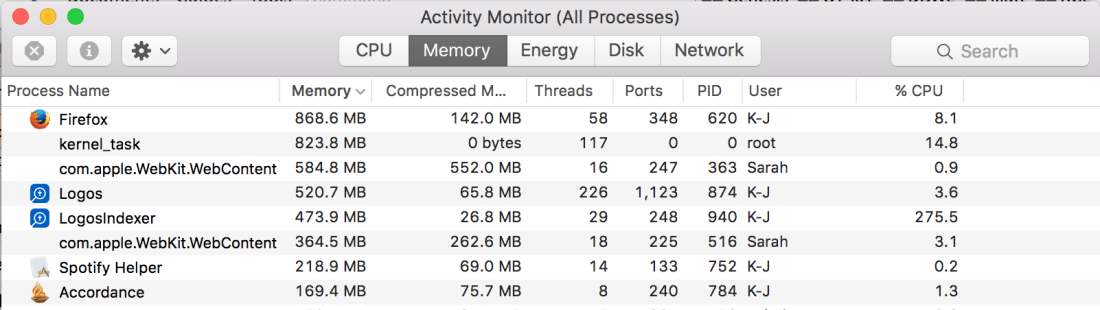

You can find the book at Amazon or at the publisher’s page. It’s available in both Accordance and Logos Bible software programs, too.

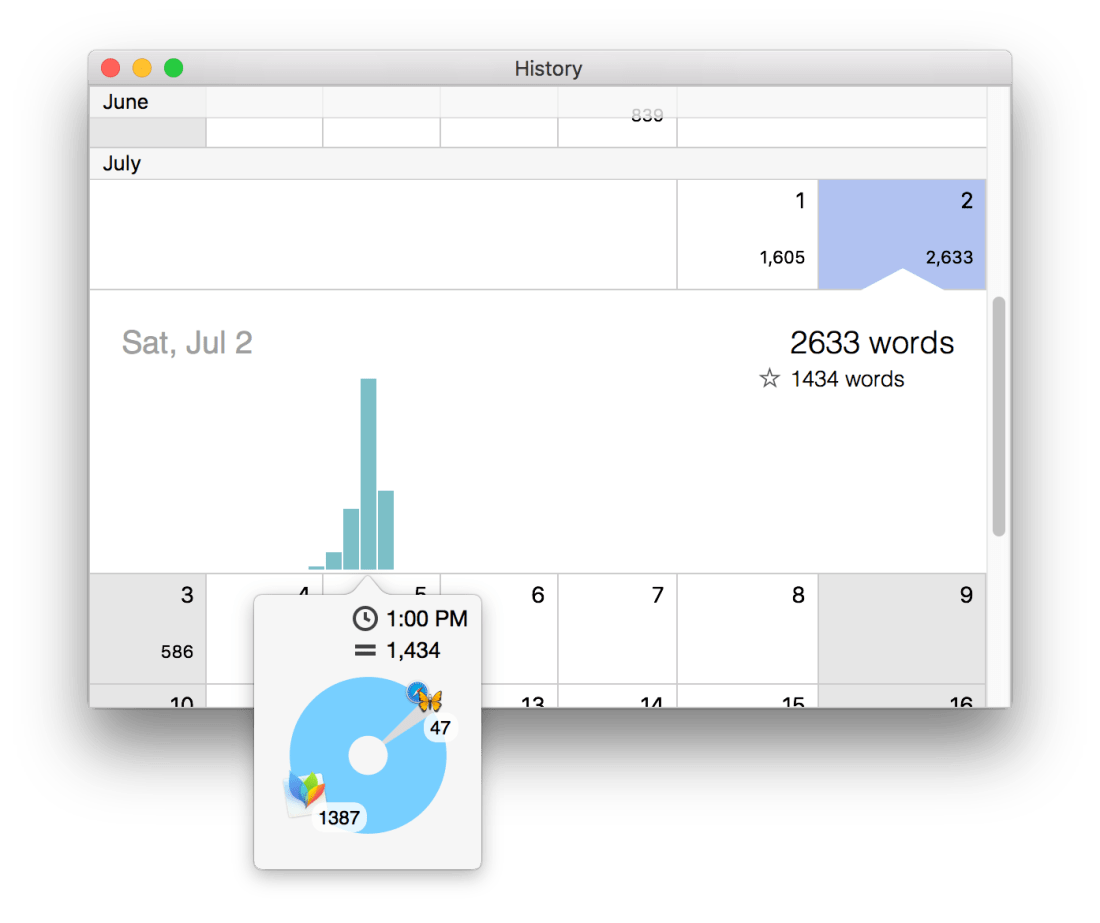

Thanks to Zondervan for the review copy, given to me with no expectation as to the review’s content, and certainly not with the expectation of a 2,000 word review essay!