The last two years have seen the appearance of two significant resources for Septuagint reading: the recently released reader’s Septuagint and Karen Jobes’s Discovering the Septuagint: A Guided Reader (Kregel, 2016). I reviewed Jobes’s volume here when it came out. Today Accordance Bible Software has released its edition.

A couple of quick notes: (1) Accordance set me up with a review copy so I could write about it and (2) much of the below draws on or quotes my review of the print edition, albeit with an eye toward the use of the Guided Reader in Accordance specifically.

Short, one-sentence version: Accordance takes an already good (and long-awaited) resource and significantly enhances its usability for readers of the Septuagint.

Below is a longer review of the resource, in Q & A format.

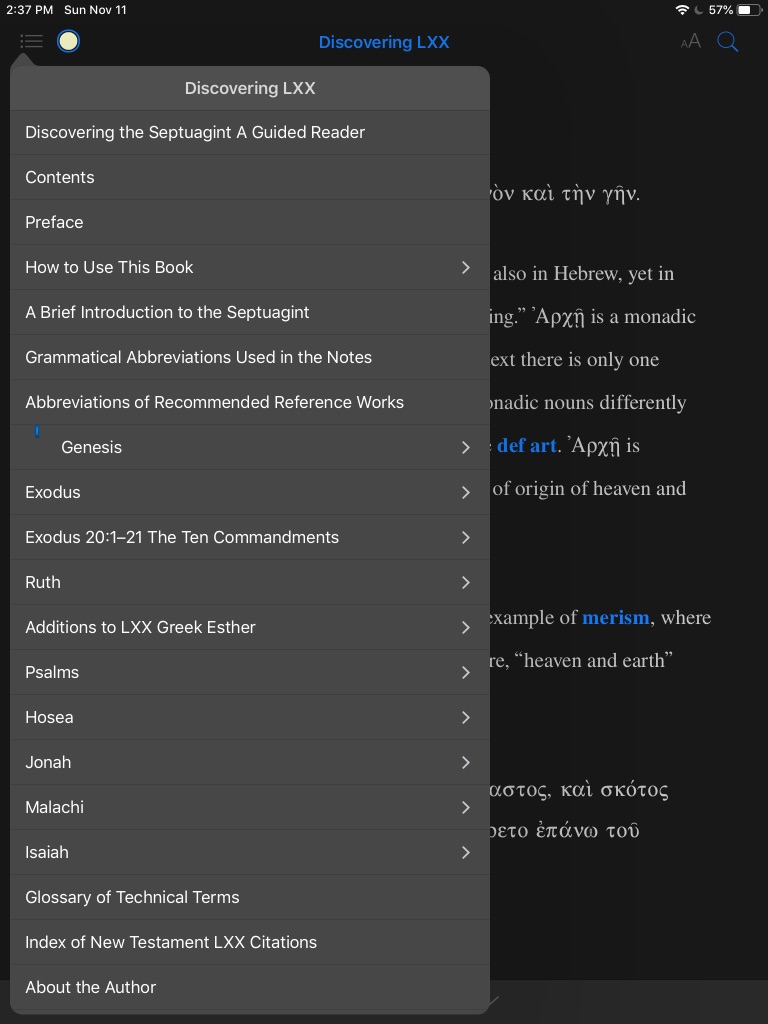

What books of the LXX are covered?

There are ten readings, meant to “give readers a taste of different genres, an experience of distinctive Septuagintal elements, and a sampling of texts later used by writers of the New Testament” (9). Discovering the Septuagint treats nearly 700 verses from:

- Genesis (80 verses)

- Exodus (79 verses)

- Exodus 20:1–21 // Deuteronomy 5:6–21 (The 10 Commandments)

- Ruth (85 verses)

- Additions to Greek Esther (73 verses)

- Psalms (67 verses)

- Hosea (56 verses)

- Jonah (48 verses)

- Malachi (55 verses)

- Isaiah (81 verses)

For whom is this book?

Jobes says it “contains everything needed for any reader with three semesters of koine Greek to succeed in expanding their horizons to the Septuagint” (8). This felt right as I worked through the resource. I found the book easy to understand (though I’ve had more than three semesters of Greek).

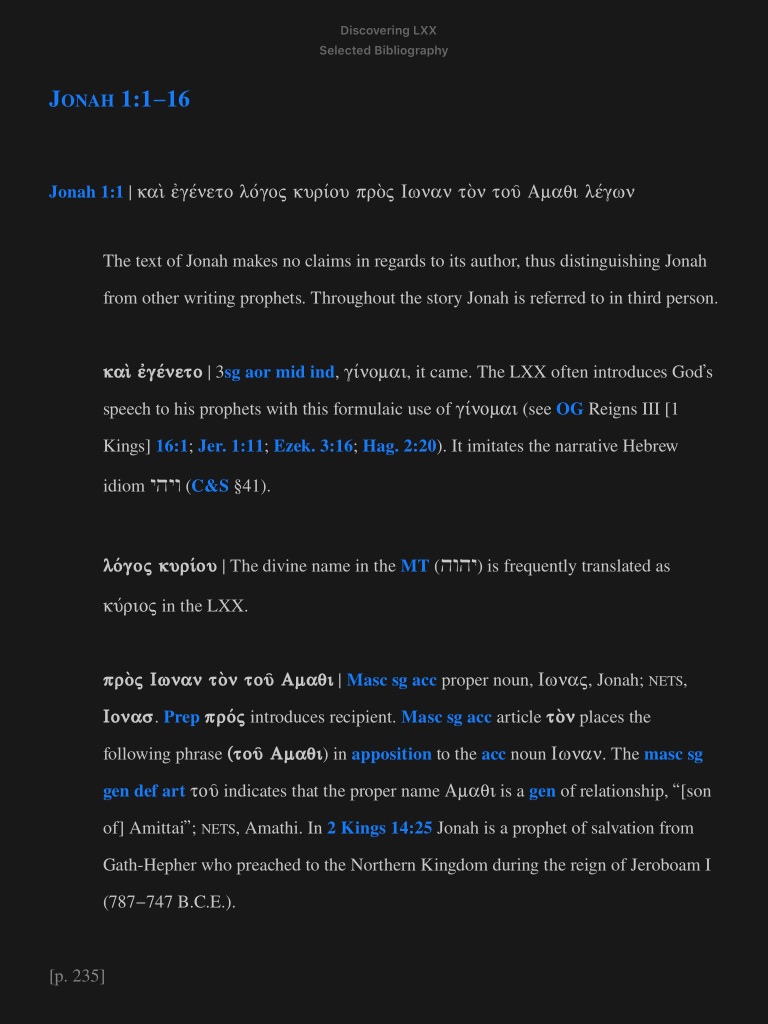

How is the book structured?

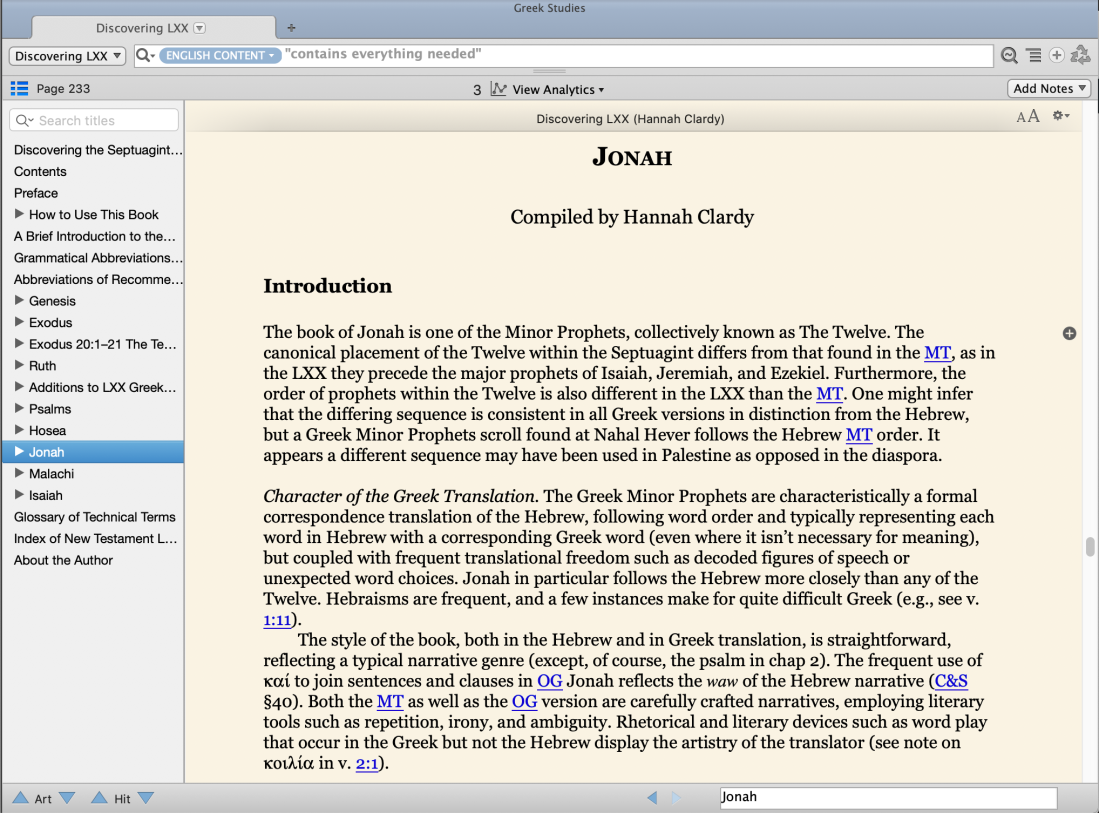

Each LXX book has a short introduction followed by a selected bibliography. Here, for example, is the intro to Jonah, shown on the Mac version of Accordance:

Next there is the passage itself, verse by verse, with the Greek text re-printed in full. Under each verse are word-by-word and phrase-by-phrase comments on the vocabulary, usage, syntax, translation from Hebrew (the book is strong here), and so on. Following each passage is the NETS (English translation) and mention of any NT use (if applicable) of the LXX passage.

The end of the book has a three-page, 33-term glossary and a two-page “Index of New Testament LXX Citations” for the books included in the reader.

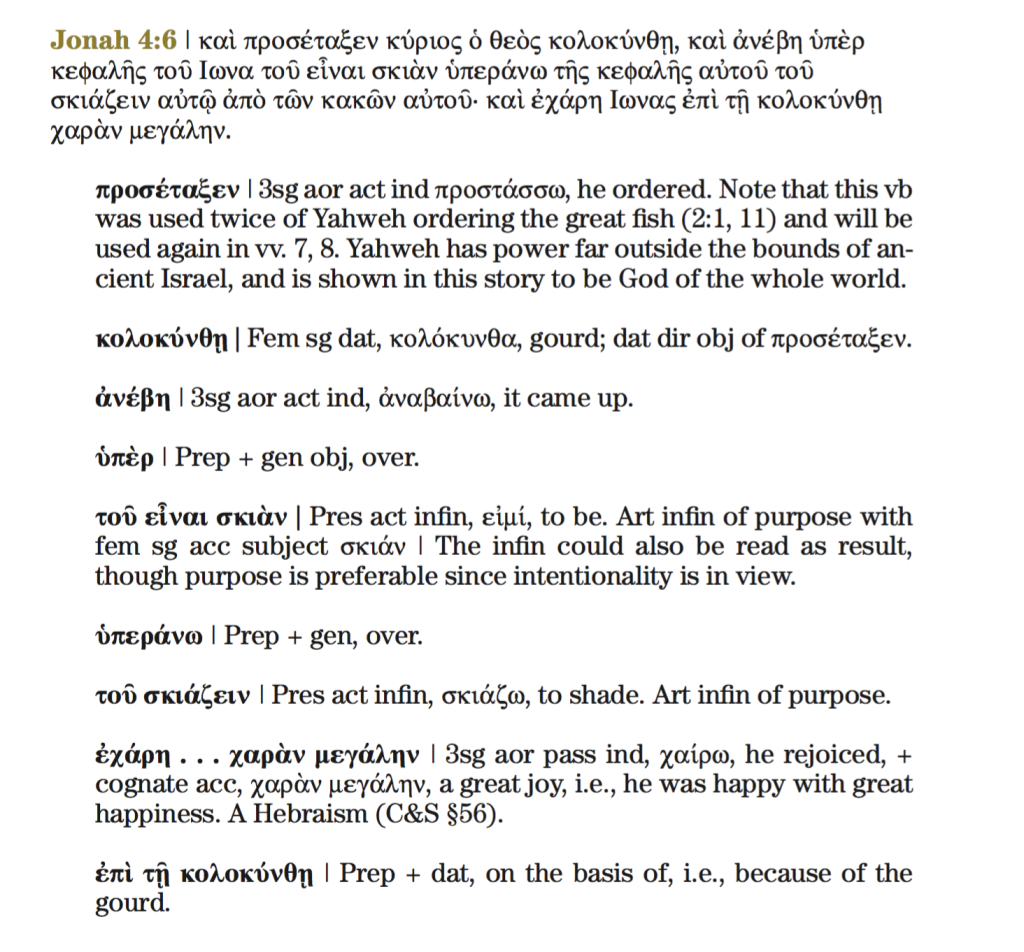

What does a sample entry look like?

Here’s Jonah 4:6 in print…

… and in Accordance, which I got to in under a second by setting the search field to “Reference” and typing in “=Jon 4:6”:

What’s commendable about Discovering the Septuagint?

The very existence of this resource is a boon to Greek readers. There long has existed Conybeare and Stock, as well as some passages in Decker’s Koine Greek Reader, but readers of the Septuagint have far fewer resources than readers of the Greek New Testament.

While the text edition has plenty wide margins for students to jot down their own parsings, translations, and notes, the margins of the Accordance edition give you a plus icon that will allow you to do the same in Accordance.

Notes on the verses are often answers to questions I’ve had as I’ve read the Greek text. In this sense the reader is a great guide. For example, here is a comment from Genesis 1:4:

ἀνὰ μέσον…ἀνὰ μέσον | Idiomatic prep phrase, “between.” This is a Hebraism, so there is no need to translate the second of the pair as NETS does.

And another helpful nugget from Genesis 1:11:

κατὰ γένος | Prep + neut sg acc (3rd dec) noun, γένος, kind. Remember the nom and acc forms are identical in this paradigm. Agrees with and modifies σπέρμα.

Accordance adds hyperlinks to abbreviations, so that you only have to hover over them to see what they stand for.

What is lacking? (And how does the Accordance edition make up for it?)

The glued binding didn’t do justice to a book like this, but that’s obviously not an issue here. Plus, portability is high, and you can read your Septuagint passages at night in dark mode on iOS!

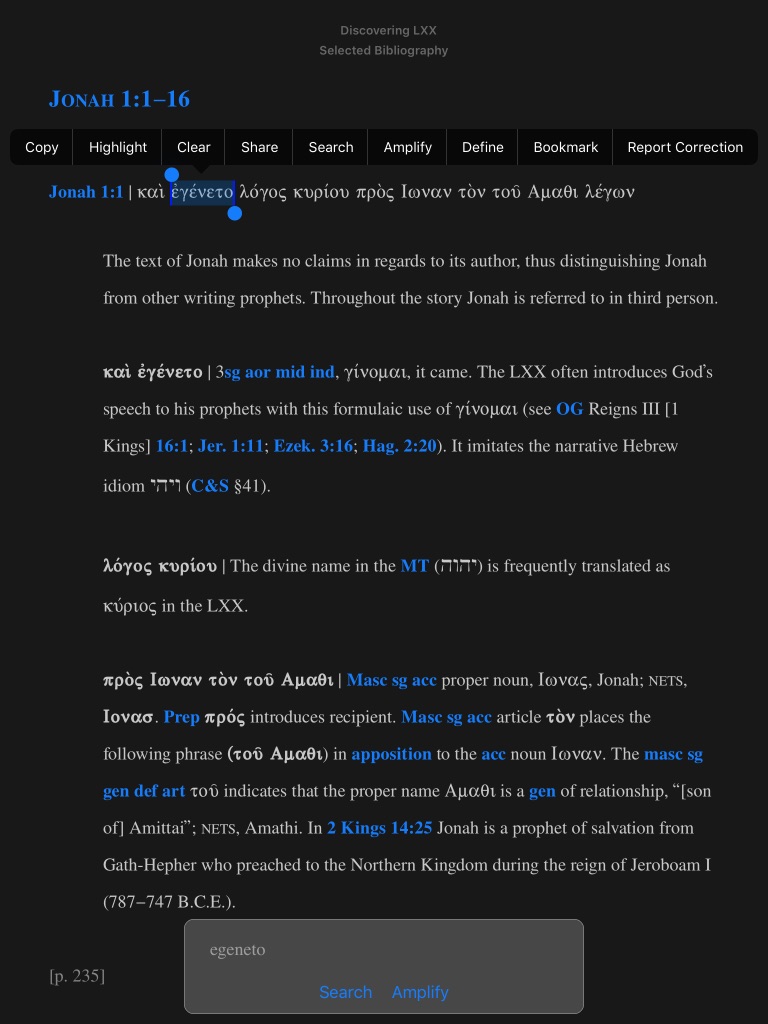

As I noted in my review of the print edition, there is a peppering of vague statements like this one on “the image of God” in Genesis 1:26: “See a commentary or study Bible” (31). And the book introductions could have done more to talk about specific Greek issues in that given book. Accordance, however, makes it super-easy to get from this resource to another, whether a study Bible or any other. Just selecting a word, for example, gives you options to search it in another resource. Like this on iOS:

All in all, Discovering the Septuagint is worth owning, and the Accordance edition significantly increases its value. There is a lot of Greek help to be had here.

Discovering the Septuagint is available in print from Kregel and here from Accordance, where it is currently on sale.