Look at that! It’s an all-Greek Bible. Just like the one Jesus carried around! Okay, not quite, but it is very good to see the Greek Septuagint and the Greek New Testament together under one cover. Augustine would be pleased:

For Greek aficionados—a 2-in-1 resource that’s designed specifically for extensive research, textual criticism, and other academic endeavors. Featuring both the Rahlfs-Hanhart Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament) and the 28th edition of the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece, this user-friendly tool includes critical apparatus, cross-references, and more. 3216 pages, hardcover from German Bible Society.

What It Looks Like

It’s a mere three pounds (in weight, not price). Amazon lists its dimensions as 7.5 x 5.7 x 2.8 inches.

This impressive edition is two previously published Greek texts put together in one cover. It’s obviously thicker than the Septuagint alone, and just a little bigger in length and width. Here are the two side by side: the Septuagint alone on the right, and its “upgrade” version (with GNT) on the left:

Before receiving the volume, I was concerned that its 3,000+ pages would defeat Alfred Rahlfs’s initial intention to have a Handausgabe (i.e., a manual and portable edition). Indeed, Hanhart’s “Introductory Remarks to the Revised Edition” translate Handausgabe as “pocket-edition,” which this is decidedly not. (It would fit nicely in a purse or man-purse, though.) That said, the addition of the Greek New Testament really does not add a lot of bulk, as Rahlfs-Hanhart was already more than 2,000 pages. Biblia Graeca is still a (fairly) portable edition, though, if not literally pocket-sized. The sewn binding and hard cover appear that they will hold up under regular use. Here are v. 1.0 (LXX only) and v. 2.0 (LXX+GNT) stacked on top of each other:

You can barely make it out from the above photo, but the LXX/GNT combo comes (wisely) with two ribbon markers. Was it a coincidence that mine were both placed at the beginning of Odes? I think not.

The Greek Typesetting/Font

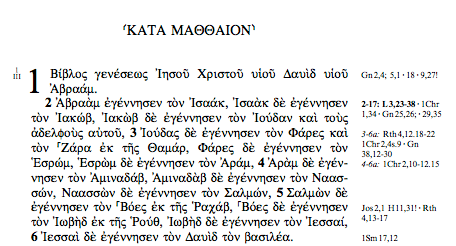

Rahlfs has not been re-typeset, so its Greek font is not as crisp or readable as that of the New Testament portion. Compare:

Here now is the Greek in the New Testament portion, which is clear and crisp:

After reading enough Septuagint, one does get used to the Rahlfs font. It’s not too bad.

Always a concern with Bibles this big is that the requisite thin pages will mean bleed-through of text from the reverse side. This is noticeable to a degree here, but not in a way that negatively affects reading:

Rahlfs-Hanhart (Septuaginta)

The Rahlfs-Hanhart edition is not the go-to for extensive text-critical research that the Göttingen editions are, where they are present (on which, see my posts here and here on using Göttingen). Rahlfs is still useful, though, because it contains an entire Septuagint text, whereas Göttingen (published as individual volumes) does not.

It is probably the best starting place for readers of the Septuagint, even with its deliberately more limited apparatus. It is best thought of as a “semi-critical edition,” as noted here. Rahlfs “reconstructs” the text using, primarily, Codex Vaticanus (B), Codex Sinaiticus (S or א), and Codex Alexandrinus (A), a methodology that the revisor, Robert Hanhart, honors. Here is the apparatus for the first page, covering Genesis 1:1-14. This is a funny case, because of how much of Genesis is missing in B, so Genesis 1-46:28 up through the Greek word ηρωων is just based on A here. The rest (from πολιν in 46:28 to the end, chapter 50) take into account B and A.

Preceding the actual text and apparatus are Hanhart’s 2005 “Introductory Remarks to the Revised Edition” in German, English, and Greek. Then in German, English, Latin, and Greek follow three more sections: (1) Rahlfs’s “Editor’s Preface,” (2) an illuminating 10-page essay, “History of the Septuagint Text”, and (3) Explanation of Symbols. Everything you need to get started reading the Septuagint (minus the Greek lessons) is here.

Nestle-Aland 28th Edition (Novum Testamentum Graece)

What about the updated NA28? In short:

The long-awaited 28th edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece has now been published. Once again the editors thoroughly examined the critical apparatus and they introduced more than 30 textual changes in the Catholic Letters, reflecting recent comprehensive collations. With the intent to make this book more user-friendly, the editors also revised the introductions and provided more explanations in English. This concise edition of the Greek New Testament, which has now grown to 1,000 pages, will continue to play a leading role in academic teaching and scholarly exegesis.

The NA28 has its own snazzy site here. (What a day we live in, when a Greek Bible gets its own Website! Its writers would be amazed.) Recent text-critical work on the New Testament has led to revisions in the Catholic Letters, but not elsewhere. So the Gospels and Pauline epistles, for example, retain the same text as the NA27. However, there are changes that affect the whole edition, as the publisher points out:

- Newly discovered Papyri listed

- Distinction between consistently cited witnesses of the first and second order abandoned

- Apparatus notes systematically checked

- Imprecise notes abandoned

- Previously concatenated notes now cited separately

- Inserted Latin texts reduced and translated

- References thoroughly revised

As for the textual differences themselves, those are explained and listed here. There are more details to be digested about the new NA28 edition. I can do no better than to refer you to the writings/reviews of Larry Hurtado, Rick Brannan, Daniel Wallace, and Peter Williams.

All the quick-reference inserts you need to make sense of symbols and abbreviations are included:

Concluding Thoughts: Sell All You Have?

The product page for the beautiful Biblia Graeca is here for CBD, here at the German Bible Society, here at Hendrickson, and here for Amazon. And, best yet, you can look at a sample of the book here. If it’s just the text (and not the apparatuses) that you’re interested in, you can read the NA28 online here and the Rahlfs-Hanhart Septuagint here.

Rahlfs wrote in his preface that he sought to “provide ministers and students with a reliable edition of the Septuagint at a moderate price.” If you click the links above, you will see that this is not “a moderate price.” It’s significantly cheaper to buy the same critical editions of each Testament under separate cover.

But there are at least two major advantages to putting them together. First, when the New Testament writers quoted Scripture, they predominantly did so in a form that is closer to what we have now in a Septuagint text. Comparing a quotation (in Greek) with its source (in Greek) is facilitated by this edition. Second, that this edition exists is an important symbolic statement. Lovers of the Septuagint are fond of affirming that it was the Bible of the early Church. If that is so, why can we not have one, too? Now we can, printed and bound in a way that would shock the pre-printing press world that first heard all these Scriptures together when gathered for worship.

Professor Ferdinand Hitzig has often been quoted saying, “Gentlemen!” (and today, he would say, “Ladies!” too) “Have you a Septuagint? If not, sell all you have, and buy a Septuagint.”

In true biblical storytelling fashion, he is using hyperbole to communicate his point. But for those who are so inclined and able, if selling a few things to get a Septuagint is a good idea, how much more might someone like Hitzig encourage them to sell a few things for the Biblia Graeca?

Christians believe that the Septuagint has come to full fruition through the New Testament.

So it only makes sense to be binding the two together.

Many thanks to Hendrickson for the privilege of reviewing this fine work. A copy came my way for review, but with no expectation as to the nature of my review, except that it be honest.