The next generation of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) is the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ). I’ve written more generally about scholarly editions of the Hebrew Bible, and have reviewed the BHS module in Accordance already. In this post I review BHQ in Accordance.

Some excellent scholarly treatments of the BHQ have already appeared. Anyone serious about learning how to use this resource discerningly (as all text critics must be discerning) will do well to avail themselves to these, probably in this order:

- Emanuel Tov: “The Biblia Hebraica Quinta–An Important Step Forward” (PDF). Tov says the BHQ is “much richer in data, more mature, judicious and cautious than its predecessors. It heralds a very important step forward in the BH series.” Yet at the same time, “This advancement implies more complex notations which almost necessarily render this edition less user-friendly for the non-expert.” That said, anyone who reads Tov’s 11-page introduction will be well-equipped to begin making use of BHQ.

- Richard D. Weis: “Biblia Hebraica Quinta and the Making of Critical Editions of the Hebrew Bible.” Weis has served as a member of BHQ’s editorial committee, so he is able to offer some good detail on “philosophical and pragmatic choices” made in publishing the editions. His article includes full sample pages of the print edition, too.

- Blogger John F. Hobbins: “Taking Stock of Biblia Hebraica Quinta” (PDF). As I will note below, the oft-appearing, seldom-explained “prp=propositum=it has been proposed” of the BHS is replaced in BHQ with more conservatism in suggesting emendations. But Hobbins calls this “the chief drawback of BHQ” and writes “in defense of conjectural emendation” as it would appear in the apparatus. Not all text critics will agree–and many will appreciate BHQ’s approach–but his argument is compelling all the same.

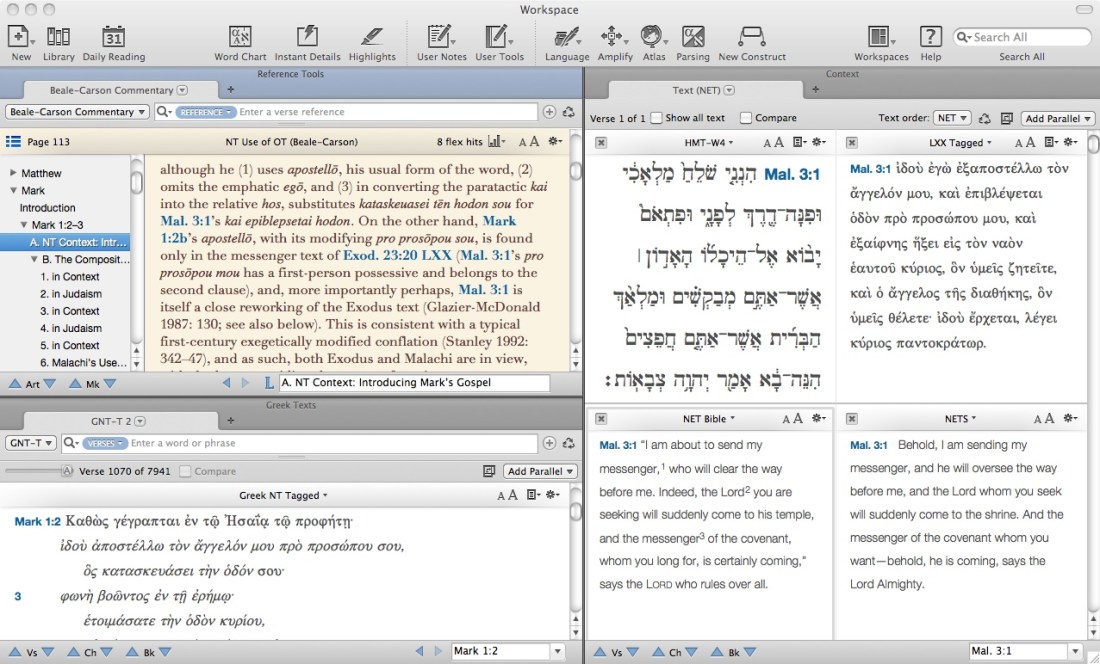

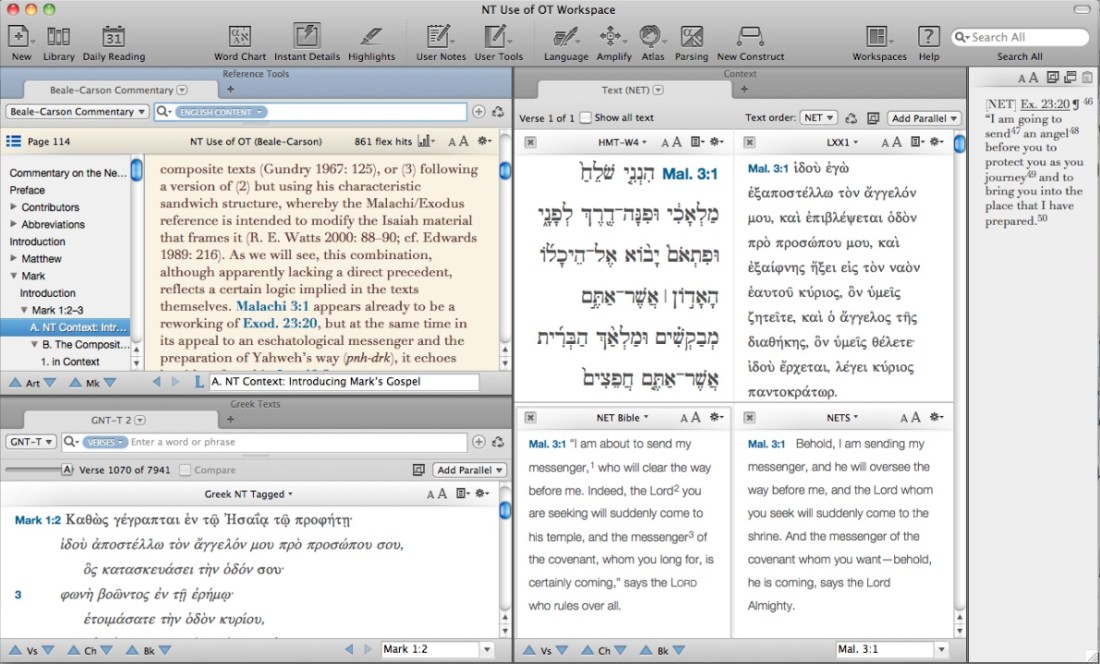

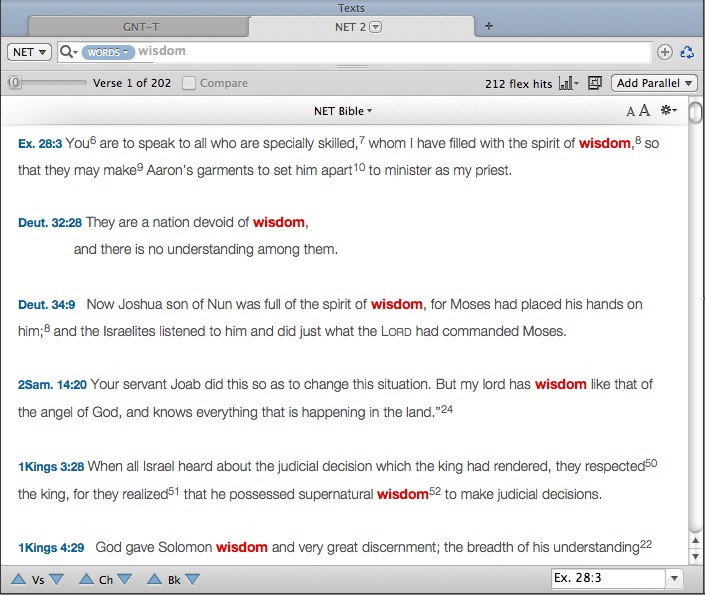

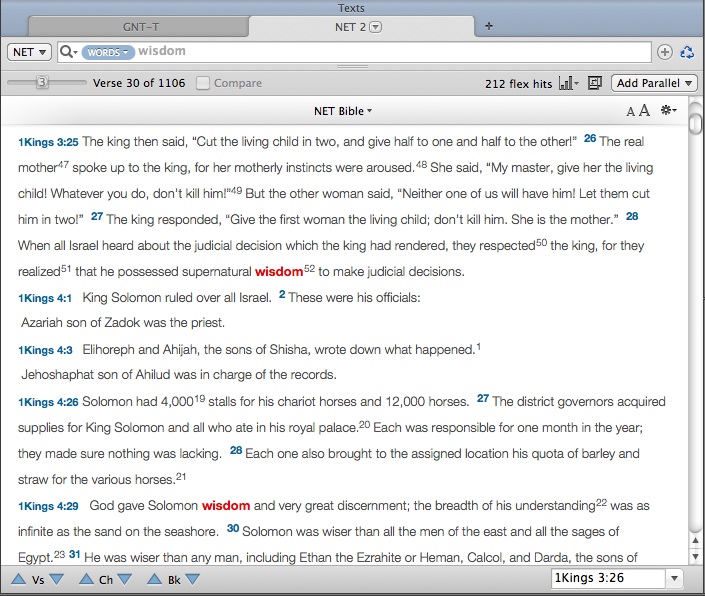

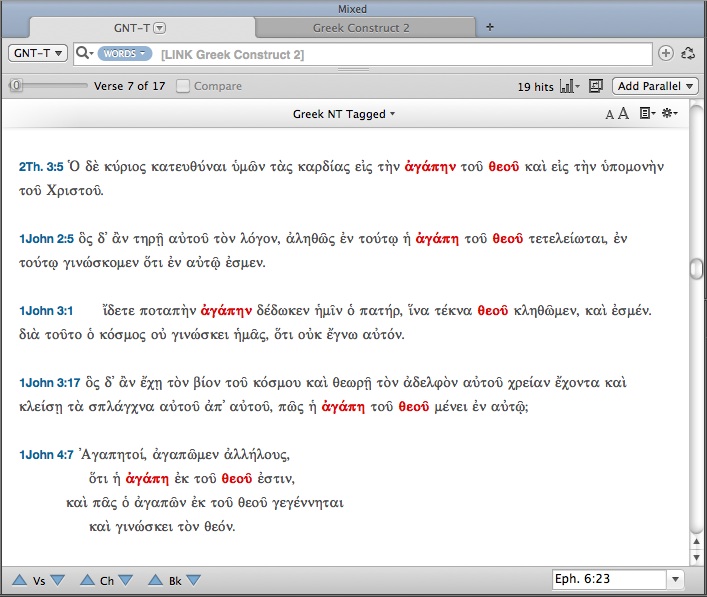

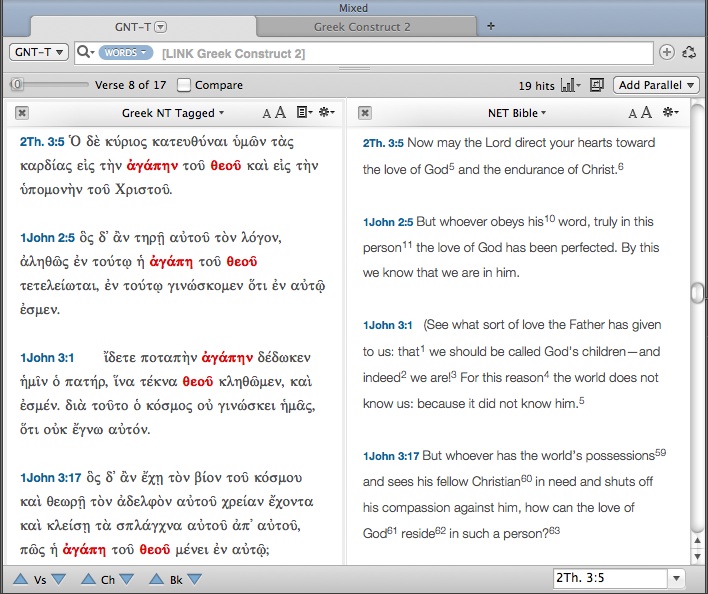

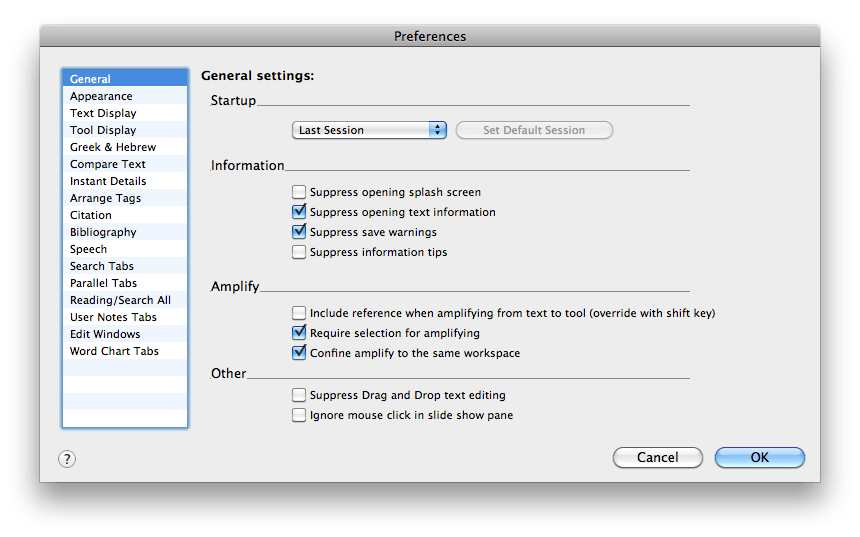

Taking the BHQ for a spin alongside the BHS is perhaps the most helpful way to see how the two compare. It’s easy to have both side-by-side in Accordance. Here’s my workspace for reading the Hebrew Bible with BHS, BHQ, the apparatus for each, and the BHQ commentary. You can click or open in a new tab to enlarge.

You can see that the text of Deuteronomy 6:4-5 above is unchanged in the BHQ. Consonants, vowels, and cantillation marks are all the same. As the BHQ is based on the Leningrad Codex, just as the BHS is, the text itself is largely unchanged. (The BHQ, however, corrects the BHS to the Leningrad Codex based on new color photographs.)

Note that abbreviations in the BHQ apparatus are now abbreviations of English, not Latin. Those who have learned how to make use of the abbreviated Latin in the BHS apparatus may be somewhat disappointed to not be able to put that knowledge to use (and to have to learn a new system), but in the end this makes for a more widely accessible apparatus, in my view.

A comparison between the BHS apparatus and the BHQ apparatus at the same point is instructive. For Deuteronomy 6:4 BHS has a superscript “a” in the text after שְׁמַ֖ע, directing to footnote a, which reads: “𝔊 pr nonn vb.” I write here about the use of Accordance to quickly decipher the abbreviated Latin in the BHS critical apparatus. “𝔊 pr nonn vb” means something like, “The Old Greek/Septuagint puts before [שְׁמַ֖ע] several words.”

It’s easy enough, especially in the workspace how I have it set up above, to find out what these Greek words in question are: Καὶ ταῦτα τὰ δικαιώματα καὶ τὰ κρίματα, ὅσα ἐνετείλατο κύριος τοῖς υἱοῖς Ισραηλ ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ ἐξελθόντων αὐτῶν ἐκ γῆς Αἰγύπτου. But the BHS alone does not give the reader much more guidance than that.

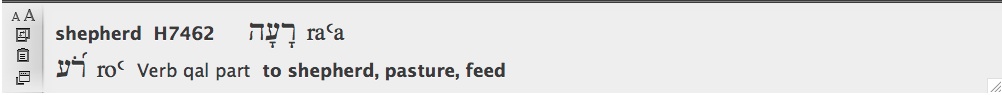

The BHQ apparatus, however, reads: “שְׁמַ֖ע Smr V S T | prec 4:45 Nash G ✝ •” Note that instead of a superscript letter in the text with the same letter as a footnote in the apparatus, the text of the BHQ is unmarked, and the apparatus note simply preceded by the word (שְׁמַ֖ע) under consideration. Some will find this gives the text an uncluttered feel; others may find it takes extra time to match text to apparatus. Hovering over the (all in English!) abbreviations in the BHQ in Accordance shows that the note says something like, “The Samaritan Pentateuch, Vulgate, Syriac, and Targumim all begin with just שְׁמַ֖ע. In the Nash Papyrus and Old Greek שְׁמַ֖ע is preceded by the text from Deut. 4:45.” Then the ✝ notes that the BHQ commentary gives the matter more discussion. For text criticism, I have been thrilled about the addition of an included-in-the-book commentary on the text and apparatus.

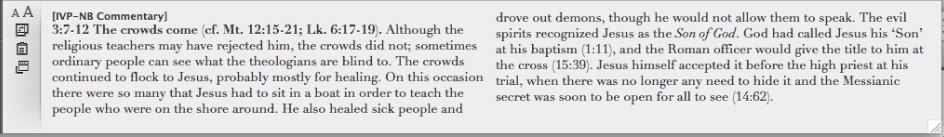

The BHQ commentary at this verse reads:

The Shemaʿ in both the Nash Papyrus and G is prefaced by an introduction taken from 4:45 with the following differences: both attest a cj. before אלה; both omit העדות and the cj. attached to the following word; both read צוה for דבר, but with “the Lord” as subject in G, whereas the Nash Pappyrus and some G Mss follow M in reading “Moses”; finally, both insert במדבר after “Israel.” For further background to the combination of certain biblical passages for liturgical reading, with particular reference to this addition in G and the Nash Papyrus, see Elbogen, Jewish Liturgy, 193. The six extant phylacteries follow M.

Thumbs up here for the additional detail provided in the BHQ apparatus and commentary and for Accordance’s presentation of it. In the print edition the commentary is in a section of the fascicle that is separate from the apparatus. In Accordance you can easily lay it all out together and see it at once.

Just as BHS was, BHQ is being published in fascicles, so a bit at a time. The following six already exist in print:

- Fascicle 5: Deuteronomy

- Fascicle 7: Judges

- Fascicle 13: The Twelve Minor Prophets

- Fascicle 17: Proverbs

- Fascicle 18: General Introduction and Megilloth (i.e., Ruth, Canticles, Qoheleth, Lamentations, Esther)

- Fascicle 20: Ezra and Nehemiah

The BHQ module in Accordance has fascicles 5 (Deuteronomy), 18 (General Introduction and Megilloth), and 20 (Ezra and Nehemiah) so far. 13 (The Twelve Minor Prophets) and 17 (Proverbs) will be added free of charge to those who have the BHQ package. They exist in print but have not yet come from the German Bible Society to Accordance for digitization. When Judges comes to Accordance, it and future fascicles will be available as paid upgrades.

Accordance has produced a short video that shows a couple ways to use the BHQ, including a comparison with the print edition. It’s worth watching, since it explores not only the text, apparatus, and commentary that I cite above, but also the Masorah Magna (below the text in the print edition) and the Masorah Parva (at the margins of the print edition). Note especially (early in the video) how Accordance merges the Notes on the Masorah to eliminate the user’s need to go back and forth between references:

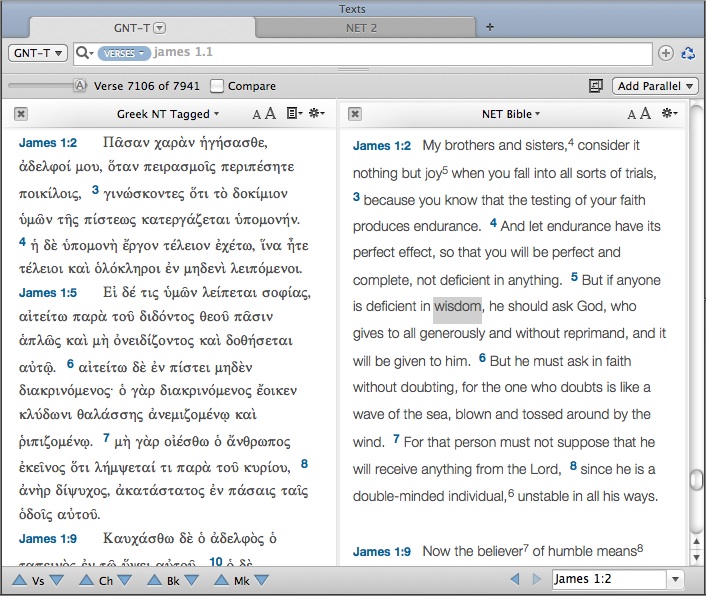

The place for the BHQ user to start is probably with the three articles at the beginning of this post. Then, the General Introduction contained in Fascicle 18 should be consulted. As with its other commentaries and books, Accordance has it presented beautifully. The English introduction tells what BHQ is, gives advice on how to use it (including full explanations of sigla and abbreviations), and tells a bit of background on the editorial processes leading to the BHQ as it is now. Click on the below for a larger image of the general introduction:

BHQ in Accordance is not morphologically tagged; Accordance does not currently have plans to tag it. But this is because the text is so similar to that of BHS already. Because I am so used to BHS and BHQ is still so new on the scene, I always have both open anyway, so I can easily get morphological tagging information from BHS. A tagged BHQ would be ideal, but it’s not a huge loss.

BHQ has less conjectural emendation than BHS. Case in point, “prp” (=”propositum”=”it has been proposed”) occurs 2,146 times in the BHS apparatus (a search that is exceedingly easy to do in Accordance). In BHQ what goes into “prp” is teased out a bit more. From the introduction to BHQ:

In cases where the editor proposes that a reading other than that of the base text is to be preferred, this is presented in the concluding portion of the entry following a double vertical stroke and the abbreviation “pref” (for “preferred reading”). The evidence supporting the preferred reading is recapitulated. If the preferred reading is not directly attested by any of the extant witnesses, but is only implied by their evidence, it is marked by the signal “(origin)”, i.e., that it is the indirectly attested origin of the extant readings. If the grammatical form of the preferred reading is not found otherwise in Hebrew of the biblical period, it is marked either as “unattest” (= “unattested”) or as “conjec-phil” (= “philological conjecture”), depending on the kind of external support for the reading. Where the proposed reading is a conjecture, it is not introduced by the abbreviation “pref” (= “preferred reading”), but by the abbreviation “conjec” (= “conjecture”). In line with the focus of the apparatus on the evidence of the text’s transmission, proposals for preferred readings will not seek to reconstruct the literary history of a text. Readings that are judged to derive from another literary tradition for a book will be characterized as “lit” (see the definitions of characterizations below).

Also,

Since the apparatus is devoted to the presentation and evaluation of the concrete evidence for the text’s transmission, a hypothetical reading (i.e., a conjecture) will have place in the apparatus of BHQ only when it is the only explanation of the extant readings in a case.

“Pref” occurs 201 times in the apparatus in the three fascicles so far published in Accordance. A primary difference in BHQ, though, is the level of textual or manuscript-based explanation given for why a certain reading is to be preferred. As someone who tries to be a cautious textual critic, I appreciate this.

Here are some additional resources for using BHQ:

- A review of Fascicle 18 in Review of Biblical Literature (PDF)

- A sample set of pages (print edition) of BHQ (PDF)… and note here that a .pdf of BHQ is not part of Accordance’s module

- Accordance’s press release for BHQ

- The product page for BHQ in Accordance

At least three things make it worth seriously considering adding BHQ in Accordance to your library. First, BHQ is a significant advance over BHS. Second, Accordance’s presentation of BHQ makes using it easier than it is in print. Third, the print editions would cost you just as much as or more than buying BHQ in Accordance. And, of course, an Accordance module is word-searchable, lighter to carry around, and so on.

All in all, BHQ in Accordance is well-produced, easy to use, and a great aid in textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible.

Thank you to Accordance for providing me with a copy of the BHS and BHQ modules for review. At the time of this writing, the sale price for that package was $149.99, an excellent deal. See all the parts of my Accordance 10 review (including the Beale/Carson commentary module) here. I reviewed BHQ’s predecessor, BHS, here.