Engagement with the Psalms—reading them, owning them, singing them, praying them, and taking cues from them—is vital for robust worship and spiritual formation in the church. If they truly are “a Bible in miniature,” as Luther has said, they offer the opportunity for the church to grow in its spiritual and emotional maturity.

Descriptive, Prescriptive

The writers of the Psalms give language to the whole range of emotions: from gratitude to fear, from joy to lamentation, from petition to thanksgiving, from intimate, private prayers to national, corporate prayers. In this way they are eminently descriptive of the human experience.

The Psalms also prescriptively guide the reader into various postures of prayer, so that the one praying does not only ever approach God with petitions, or only ever with complaint, and so on. The cognitive and affective come together in the Psalms in sometimes unexpected ways. Psalms of lament, for example, often begin with a loud “Why?” (stressing the affective) yet end with a determined profession of faith like, “But I will trust in you still….” In this way they stress the use of cognitive powers in prayer—external life evidence notwithstanding!

The Psalms express (descriptively) and call forth (prescriptively) a whole spectrum of human experience in relationship to God. They teach us to bring our whole selves to God in worship.

Preaching the Psalms

But how to preach them? One will need to take into account intercultural realities. Understanding the role of a shepherd in ancient society will certainly help with Psalm 23. And soul-searching is required.

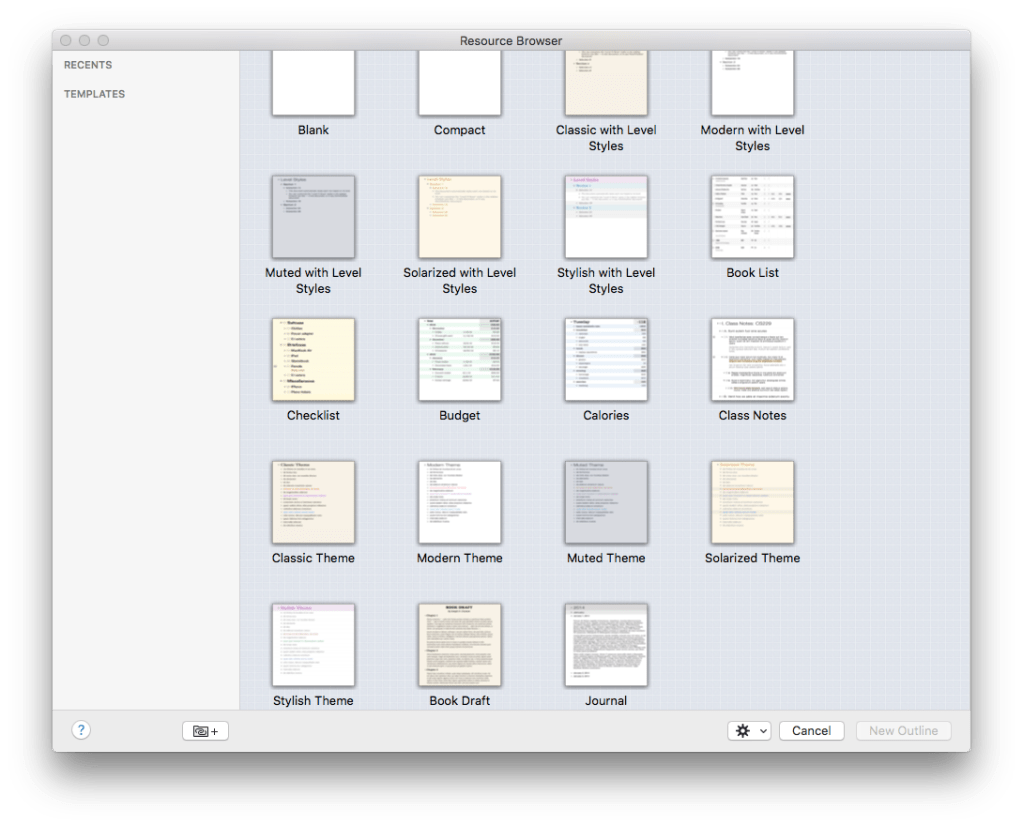

A good set of commentaries helps, too. I preached some Psalms a couple summers ago, and found these two options quite helpful.

Just completed, too, is Allen P. Ross’s three-volume, multi-thousand page commentary on the Psalms, published by Kregel Academic.

Ross’s Commentary, in Three Volumes

Volume 1 has more than 150 pages of introductory material, covering:

- “Value of the Psalms” (Ross says, “It is impossible to express adequately the value of the Book of Psalms to the household of faith”)

- “Text and Ancient Versions of the Psalms”

- “History of the Interpretation of the Psalms”

- “Interpreting Biblical Poetry”

- “Literary Forms and Functions in the Psalms” (the best starting place, I thought)

- “Psalms in Worship”

- “Theology of the Psalms”

- “Exposition of the Psalms”

I haven’t seen the just-released third volume, but Kregel was kind to send me the first two volumes for review. In what follows I interact with those books. Volume 1 covers Psalms 1-41; Volume 2 treats Psalms 42-89.

The Commentary Layout (Psalm 42 as Case Study)

Even in the Table of Contents you can get a sense of where Ross will go with a given Psalm, as each Psalm listed includes summary titles. Psalm 1 is “The Life That Is Blessed.” Psalm 23: “The Faithful Provisions of the LORD.” Psalm 46: “The Powerful Presence of God.” Psalm 51: “The Necessity of Full Forgiveness.”

Introduction to the Psalm

Then there follows Ross’s introduction to the Psalm. He provides his own translation from Hebrew with extensive notes, analyzing the text and textual variants. Psalm 42:2, for example, he translates:

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God.

When shall I come and appear before God?

His footnote offers a point of interest: “This first ‘God’ is not in the Greek version; it simply reads ‘for the living God.’” He often has the Septuagint in view, which I especially appreciate. On Psalm 42:9, for example (“I say to God, my rock…”), he notes:

The Greek interprets the image with ἀντιλήμπτωρ μου εἶ, “you are my supporter/helper.”

Not that every footnote “will preach,” but they don’t need to—Ross offers a wealth of insight that will help preacher, student, and professor better understand the text as it has come down to us.

Still with each Psalm’s introductory material, the “Composition and Context” session sets the Psalm in its biblical-literary context and explores background information (where available). Regarding Psalm 42, Ross says:

And Psalm 42 is unique in supplying details of the location. The psalmist is apparently separated from the formal place of worship in Jerusalem by some distance, finding himself in the mountainous regions of the sources of the Jordan. There is no explanation of why he was there; and there is no information about who the psalmist was.

Reading the commentary, one trusts that were there such information, Ross would have unearthed and presented it!

Reading the commentary, one trusts that were there such information, Ross would have unearthed and presented it!

Then there is a summary “Exegetical Analysis,” followed by an outline of the Psalm. Anyone looking to get their bearings quickly with a Psalm will find this one of the most helpful sections. Here is Ross again, with his summary of Psalm 42:

Yearning in his soul for restoration to communion with the living God in Zion and lamenting the fact that his adversaries have prevented him, the psalmist encourages himself as he petitions the LORD to vindicate him and lead him back to the temple where he will find spiritual fulfillment and joy.

Commentary in Expository Form

After each Psalm’s generous introduction, Ross presents the commentary proper (“Commentary in Expository Form”). It’s as detailed as one would expect and hope. Here he is, for example, on Psalm 42:3-4 (“They must endure the taunts of unbelievers”):

In the meantime, the psalmist must endure the taunts of his enemies—enemies of his faith. In this he is an archetype of believers down through the ages who are taunted for their faith. This has caused him tremendous grief, so much so that he says his tears have been his food night and day (see Pss. 80:5 and 102:9; Job 3:24). The line has several figures: “tear” (collective for “tears”) represents his sorrow (a metonymy of effect); “food” compares his sorrow with his daily portion (a metaphor); and “day and night” means all the time (a merism). The cause of his sorrow is their challenging question: “when they say to me continually, ‘Where is your God’?” (see Pss. 74:10 and 115:2). The unbelieving world does not understand the faith and is unsympathetic to believers. “Where is your God?” is a rhetorical question, meaning your God does not exist and will not deliver you—it is foolish to believe. For someone who is as devout as the psalmist, this is a painful taunt.

This blend of careful attention to the text and reverent devotion to the God who breathed it is typical of the Ross’s rich comments.

Message and Application

Though Ross already offers theological interpretation in the commentary proper, the Message and Application section is one any reader will appreciate. He often reads (in a good way) through a New Testament and Christological lens, as with Psalms 42-43:

But in the New Testament the greatest longing of those who are spiritual is to be in the heavenly sanctuary with the Lord, for that will be the great and lasting vindication of the faith. Paul said he would rather be at home with the Lord—but whether there or here, he would try to please the Lord (2 Cor. 5:8–9). And Paul certainly knew what it meant to be persecuted for his faith. But the marvelous part of the desire to be in the heavenly sanctuary is that the Lord Jesus Christ desires that we be there with him, to see his glory (John 14:3; 17:24). Throughout the history of the faith believers have desired to go to the sanctuary to see the LORD (see Ps. 63); in Christ Jesus that desire will be fulfilled gloriously.

Those looking for a dispassionate commentary or for one that does not find Jesus in the Hebrew Bible will be better served looking elsewhere. To my mind, this dynamic is one of the great strengths of these volumes.

Toward the end of a Psalm, then, Ross boils it down to an italicized expositional message. This is one of the (many) highlights of the commentary, as it pulls everything together from Ross’s careful exegesis into the world of the listener. Here is how he puts Psalm 23:

The righteous desire to be in the presence of the Lord where they will feed on his Word, find spiritual restoration, be guided into righteousness, be reminded of his protective presence, receive provisions from his bounty, and be joyfully welcomed by him.

Where to Get It

Here is where to find these fine books:

Volume 1: Amazon / Kregel

Volume 2: Amazon / Kregel

Volume 3: Amazon / Kregel

Thanks to Kregel for the review copies of both books, given to me for the purposes of reviewing them, but with no expectation as to the content of this post.