Is The Sacred Bridge the best Bible atlas ever? To be fair, people consult atlases for different purposes. But for the one–academic or otherwise–who wants to dig deeply into the historical geography of the biblical world, what’s the best resource available?

Is The Sacred Bridge the best Bible atlas ever? To be fair, people consult atlases for different purposes. But for the one–academic or otherwise–who wants to dig deeply into the historical geography of the biblical world, what’s the best resource available?

I believe the reviewer should evaluate a work according to its merits in relation to the aims of the work. It would not be fair, for example, to criticize a popular commentary for not being technical enough, nor to criticize a work explicitly focusing on the Greek text of a biblical book for not including enough historical background.

So it is perhaps a bit odd that I come to a review of The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (hereafter, TSB) with the question: Is it the best Bible atlas ever? It does not explicitly claim it is, nor self-consciously attempt to be. However, some copy by its publisher, Carta Jerusalem, does read, in part:

The Sacred Bridge will be the Bible Atlas of Record and Standard Work for the coming decades. Exhaustive in scope and rich in detail, with its comprehensive documentation of the Near Eastern Background to Biblical History, this latest Bible Atlas from Carta is one more stepping stone on the way to the study and understanding of the Holy Scriptures.

TSB‘s reputation precedes it. Readers of this blog know that I’m a daily user of Accordance Bible Software. It was from the Accordance User Forums that I first learned about The Sacred Bridge. Almost every mention hailed it as the best, most comprehensive Bible atlas there is. So, naturally, I was eager to test that claim for myself.

In this post I review Carta’s impressive atlas. SPOILER ALERT: The answer to my “Is it the best?” question is… yes.

Such a monumental work deserves an attentive and thorough review, which I offer here as best I can. This will not be a short review, but my aim is for anyone reading it to be able to decide whether to add TSB to their own personal arsenal of resources for reading and study. The review will follow this outline:

- Orientation to Orienteering with TSB: What are the ways one can (begin to) use the atlas? I suggest four.

- TSB‘s Construction, Layout, and Text: How is the presentation and typesetting in the atlas?

- Maps, Images, and Tables: Are the images of high quality? Are they easy to read?

- Case Study: The Sacred Bridge on The Holy Gospels: I interact more closely with an individual chapter, Chapter 22: “Historical Geography of the Gospels.”

- The Younger Sibling of TSB: Here I point out and briefly comment on Carta’s New Century Handbook and Atlas of the Bible, which is essentially a condensation of (or, set of selections from) The Sacred Bridge.

- A Few Points of Critique: Though this atlas would be difficult to make much better, I offer a few minor suggestions.

- Excursus: My Seven-Year-Old Son Loved It: This is true–I have a picture to prove it.

1. Orientation to Orienteering with TSB

A. The Jump-Right-In Method

One way to begin using The Sacred Bridge is to do what I did when I first received it: open it up and start flipping through it.

This impressive, detailed timeline greets the reader inside the front and back covers (“Chronological Overview of the Ancient Near East”):

You probably won’t be able to see much detail in the image above, but it’s legible when you’ve got it in front of you.

The Table of Contents are worth perusing, available from Carta here (PDF) or from Eisenbrauns (the North American distributor of TSB) by clicking through from the product page. One immediately notices that the atlas covers from the fourth millennium BCE through the Bar Kochba Revolt (132-135 CE).

Given my interest in Septuagint studies and Maccabees, I opened right away to Chapter 18: “The Hasmonean Struggle for Independence (167-142 BCE).” It begins:

The response to Antiochus IV’s Hellenizing campaign was quick and forceful. The writings of Josephus and 1 Maccabees recount that Mattathias son of John, a priest and leader in the village of Modiin (el-Midya; Eus. Onom. 132:16; Notley and Safrai 2005:126 n. 703) near Lydda, was one of the first offered an opportunity to submit to the king’s edict (Ant. 12:265–271).

There is also this map, “The beginnings of the Hasmonean revolt, 167 BCE”:

And then, with the battle map in view, “The Early Battles” walks the reader through the battles mentioned in 1 Maccabees 3 and 4 (Gophna, Beth-horon, Emmaus, and Beth-zur), after which subsequent sections follow the Maccabean campaigns of 1 Macc. 5 and following. This particular chapter in TSB reads like a detailed and page-turning military history:

Jonathan’s political position was tenuous. His allies were dead, and the figure he had earlier opposed was now seated on the throne in Antioch. The high priest moved to take advantage of the political diversions in Syria and attacked the Citadel in Jerusalem. Perhaps, he assumed that Demetrius II would follow his father’s pledge to empty the bastion of the Seleucid garrison and turn it over to the high priest (1 Macc 10:32)—an offer his benefactor Alexander never matched. It seems that the son of Demetrius likewise thought it better to maintain a military presence in the Citadel and demanded the Hasmonean cease his hostilities.

B. The Read-the-Introductory-Material Method

Chapter 1, “Dimensions and Disciplines,” informs the reader what kind of book The Sacred Bridge is:

This is not meant to be a textbook in geography, not even biblical geography. It is an attempt to view the geographical setting through the eyes of the ancient inhabitants. It concentrates on the terms and places that have enjoyed their attention; it seeks to define them in terms of their ancient understanding.

In pursuit of this aim, the atlas draws on “every available documentary source, Egyptian, Akkadian, Moabite, Phoenician, Greek, Latin, Arabic, etc., that may provide geographical details and perspective.” Though the first chapter is dense and technical, it alerts the reader to the various kinds of sciences (ecology, hydrology, and so on) that constitute physical geography, as well as covers disciplines like historical philology and “grammatical analysis of ancient Semitic toponyms” (!).

Then, true to the goal of describing places “in terms of their ancient understanding,” the second chapter is short, readable, and informative, titled, “The Ancient World View.” It focuses especially on the economy and commerce of the ancient world.

Chapter 3, “The Land Bridge,” describes the Levant, demarcating just what land the “Sacred Bridge” refers to: “the eastern Mediterranean littoral (with somewhat more emphasis on the southern part).” The phrase “Sacred Bridge,” funnily enough, is only used in the title of this book.

C. The Is-This-Place-Name-from-This-Bible-Verse-Here? Method

Numbers 33:49 reads:

They camped by the Jordan from Beth-jeshimoth as far as Abel-shittim in the plains of Moab.

Where is Abel-shittim? I can look it up in the index to see the pages on which it occurs.

On page 124 I read, in part:

Abel-shittim is the same as Shittim (Num 25:1); its location was east of the Jordan and north of the Dead Sea.

Then follows a description of its two proposed sites. I find full-color maps with Abel-shittim clearly marked on pages 123, 125, and 137.

Elsewhere TSB notes Abel-shittim as one of a group of “names derived from some local plant or fruit.”

Remarkably, the index lists page numbers not just where a place name occurs in the text, but also where it occurs in a map. Mizpah and Memshath, for example, are both listed as occurring on page 239, but one cannot find them in the text. Rather, they are in the map. I was impressed to see the index keyed to both text and images.

D. The Get-It-in-Accordance Method

You can do a lot of helpful specific searches of TSB in Accordance. For example, when TSB cites Eusebius’s Onomasticon (a 4th century atlas), it has Onom. in parentheses as a citation. By selecting the search field of “Content” in Accordance and typing in “Onom”, I can find every time TSB cites the Onomasticon. Searching “Onomasticon” using the same field shows me all the times that it is mentioned by name in the body of the text. Then searching “Onom <OR> Onomasticon” (without the quotation marks) shows me results for both of the above searches. Very cool! Also praiseworthy is the fact that TSB cites Eusebius both in its original Greek and in English translation. TSB is, indeed, a rich atlas. Accordance makes searching it fast, useful, and–dare I say–fun.

There is perhaps one advantage to the print edition over the Accordance edition: the index mentioned above is not included as such in Accordance, and searches for place names in Accordance do not return results for where the place occurs within an image. However, this small loss is outweighed by the versatility and quickness (and multiple ways) with which one can navigate TSB in Accordance.

2. TSB‘s Construction, Layout, and Text

TSB emphasizes “the ancient written sources.” The authors write in their foreword:

In each case we attempted to interpret every ancient passage firsthand, from the native language. Anything less than this fails to meet the high standards of original research.

Though the authors’ frequent citation of and interaction with original languages are themselves impressive (Greek and Hebrew are only the beginning), just as impressive are the typographical requirements that such a standard implies. The original language fonts are color-coded for easy viewing, sized well, crisp, and highly readable. There is also, of course, the challenge of setting images, maps, and figures alongside copious text. If there were an Academy Award for typesetting, The Sacred Bridge would be a runaway Oscar winner. Any given page would make it in to the Typesetting Hall of Fame on the first ballot. Sound hyperbolic? Check this out (open in a new tab, then click to zoom in):

The layout and construction of the book (which has sewn binding, of course) are a work of impressive mastery.

TSB is not only the best Bible atlas there is, it’s also one of the most beautiful and impressive books I’ve opened. (Its dimensions are 9.25′ x 13′, or 24 x 33 cm. If future generations judge our generation by content and presentation of The Sacred Bridge, we will be deemed to have been an exceptional one.

If there’s anything to critique about the text and layout, it’s that there’s a lot of material on each three-columned page. But with such clean, readable fonts (that really only feel a bit small in each Excursus section), reading TSB for long periods of time is just fine.

As to this second edition’s having been “Emended & Enhanced,” some of the differences in the new edition are noted here at Todd Bolen’s fine blog.

3. Maps, Images, and Tables

The maps and images are of high quality and easy to read. They work well together with the text to help the reader understand, visualize, and situate ancient places in their historical and geographical contexts.

There is even Excursus 6.1 (“The Topographical List of Thutmose III”), a multi-page, 119-item table, including hieroglyphics. It looks great in print, and Accordance presents it nicely, too.

You can both read on and look above in this post to see some of the maps of TSB. Carta has deserved its reputation as a producer of excellent, detailed maps. Not only the place names but also the travel routes and event annotations kept me spending quite a few minutes at a time with any individual map, fully engaged and fascinated by its content.

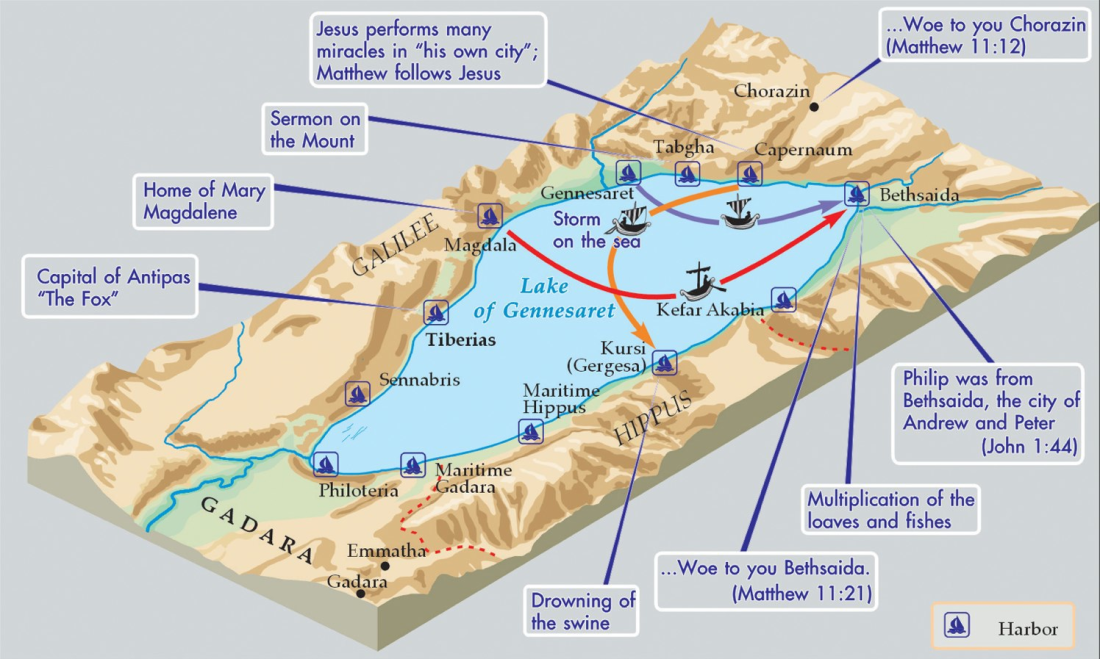

This one is a current favorite:

4. Case Study: The Sacred Bridge on The Holy Gospels

The thoroughness of The Sacred Bridge is evident throughout the atlas. In chapter 22, “Historical Geography of the Gospels,” R. Steven Notley looks at “significant events that may benefit from a historical and geographical reading of the text.” He points out: “In many instances the location and nature of the recorded sites have been lost in time.” But “modern archaeology together with a careful reading of the ancient witnesses” (especially Josephus in this chapter) give him a basis from which to elucidate the assumed geographical setting of the Gospel writers.

Here are the sections of the chapter on the Gospels:

- The Birth of Jesus and the Flight into Egypt

- The Geographical Setting for the Ministry of John and the Baptism of Jesus

- From Nazareth to Capernaum

- The Sea of Galilee: Development of an Early Christian Toponym

- The First-century Environs of the Sea of Galilee

- Literary and Geographical Contours of “The Great Omission”

- The Last Days of Jesus

- From the Empty Tomb to the Road to Emmaus

- Excursus 22.1: Jesus and the Myth of an Essene Quarter in Jerusalem

This single chapter is some 30,000 words.

The most immediately useful part of the chapter was the 3-D map of the Lake of Gennesaret, also known as the Sea of Galilee. The map is followed in the text by descriptions of Tiberias, Capernaum, and the now elusive-to-locate Bethsaida. Here is the map, which you can click or open in a new tab/window to enlarge:

And then there is the section, “The Sea of Galilee: Development of an Early Christian Toponym.” For as familiar as “the Sea of Galilee” is to the Christian lexicon, that place name only occurs, Notley rightly points out, in these verses: Matthew 4:18, 15:29; Mark 1:16, 3:7, 7:31; John 6:1. He convincingly notes:

The uncommon nature of this toponym is indicated in the Fourth Gospel by the Evangelist’s need to further define it with an additional genitive more familiar to his readers: “After this Jesus went to the other side of the Sea of Galilee [which is the Sea] of Tiberias” (Jn 6:1).

What then follows is an analysis of the references of Josephus, Pliny, and Maccabees to this lake. Notley’s command of Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic help him to unpack for the reader, among other things, why this lake is called a “sea” (haven’t you always wondered?):

We are still left with the unusual application of the term θαλασσα by Matthew, Mark and John to the Lake of Gennesar, and the related question of the origins for the Christian toponym η θαλασσα της Γαλιλαιας (Mt 4:18, 15:29; Mk 1:16, 7:31; Jn 6:1). The name ים כנרת (Sea of Chinnereth) for the lake occurs three times in the Hebrew Scriptures (Num 34:11; Josh 12:3, 13:27) and is rendered by the Septuagint θαλασσα Χενερεθ (or Χεναρα).

But Notley is not convinced that Matthew, Mark, and John drew inspiration just from the Septuagint’s rendering of the Hebrew ים as θαλασσα.

Instead, the genesis for the Christian toponym may be indicated by Matthew’s scriptural citation immediately prior to his first use of the Sea of Galilee.

This uniquely “Christian toponym” of “the Sea of Galilee” has to do with how Matthew appropriated Isaiah 9:1:

Isaiah’s intentions notwithstanding, Matthew took advantage of the Septuagint’s rendering of the common noun גָּלִיל to read Galilee. Further, the Evangelist collapsed three widely divergent points of geographical reference to a single topos—the region around Capernaum that served as the locus for Jesus’ ministry.

And:

Drawing upon the Septuagintal vocabulary of Isaiah 9:1 (Θαλασσα and Γαλιλαια), the early Church created a new toponym that provided an elliptical allusion to Isaiah’s prophecy and underscored the biblical significance of the locus of Jesus’ ministry. If our observation is correct, we can now understand how the term Θαλασσα —which in the Septuagint’s translation of Isaiah initially spoke of the Mediterranean Sea—was transferred to another body of water, namely the Lake of Gennesar.

I appreciated Notley’s tentativeness in his conclusion (“If our observation is correct”). If the reader does not agree, she or he will still find Notley’s reasoning and detailed exposition compelling, even if a re-reading or two of his argument might be warranted. (And this is just one section of one chapter of The Sacred Bridge! The book is truly a gold mine.)

That’s not even to mention “The Last Days of Jesus,” a section in this same chapter that compellingly describes Jesus’ final journey to Jerusalem, culminating in his arrest and crucifixion. It is from this section that the graphic in my section 3 above comes.

5. The Younger Sibling of TSB

The Sacred Bridge is dense, technical, and not cheap. It’s worth its price ($120 retail, a little less at Amazon), but what about another way of accessing much of the same information and maps? TSB has a younger sibling, Carta’s New Century Handbook and Atlas of the Bible (CNCHBAB).

CNCHBAB is less concerned than The Sacred Bridge is with “citing all available historical sources in their original languages.” The absence of such citations in “in their original script” is a main way in which the smaller Handbook differs from TSB.

Carta’s New Century Handbook and Atlas of the Bible is shorter, too. It omits almost all of the Excursuses of TSB, as well as omits a few whole chapters. The publisher describes it as “a select rather than a condensed version.” In “Historical Geography of the Gospels,” for example, TSB‘s detailed and technical (yet fascinating) section, “The Search for Bethsaida,” is left out altogether.

CNCHBAB is more accessible and cheaper (by about half) than The Sacred Bridge. There are entire sections in the Handbook and Atlas that appear verbatim as in The Sacred Bridge. This is good in terms of getting at the content of the latter, though not all potentially unfamiliar terminology has been explained or eliminated in the Handbook and Atlas:

The final phase of Herod’s palace in Jericho was the largest and most ornate. Concrete walls were faced with Roman-style plastering, opus reticulatum and opus quadratum, perhaps indicating the direct involvement of Roman builders and architects in the construction.

All the same, an advanced undergraduate course in religion or biblical studies could–with the guidance of the professor, as needed–make quite good use of Carta’s New Century Handbook and Atlas of the Bible for a textbook. For that matter, a seminary course could use it well, though any sort of doctoral studies–especially in archaeology or biblical geography–would call for use of the full Sacred Bridge.

6. A Few Points of Critique

My primary point of critique in using the print edition is that there is no Scripture reference index. It seems to me that one of the ways a person would come to the atlas is with a biblical verse or passage in mind, and want to find right away what TSB has on a passage under consideration. TSB in Accordance obviates the need for such an index, since one can use the Scripture search field to search the atlas by reference.

And this lack is not insurmountable in the print edition, as one can turn to the index to find any place names of interest in a particular passage. Besides, TSB covers so much primary literature, and deliberately seeks to address “every available documentary source,” such that to be true to its aim, a Scripture index would have to also be accompanied by other primary source indices. Given how many sources TSB cites, I understand the omission.

But, as noted in 1.C above, the index in TSB is well-produced, even without a Scripture index per se.

It would be unfair to fault an atlas with an academic audience for frequent use of technical terminology, so I point it out not as a critique, necessarily, but the reader should be advised of the need to know (or look up) words such as: steppe, opus reticulatum, legerdemain, sartorial, toparchy, etc. The occasional sentence, jargon aside, is lengthy and potentially difficult to follow on first read. But the overall style is readable and engaging.

7. EXCURSUS: My Seven-Year-Old Son Loved It

Bonus: TSB made for a good 20 minutes of bedtime reading with my seven-year-old son, shortly after I first received the atlas. (We’ve returned to it since then, too.) He knows the Hebrew alphabet and a little bit of Hebrew, and his Jewish friend at school had told him all about the Maccabees, so he loved looking and reading through the atlas with me! “Cool!” and “Wow!” were his most oft-used descriptors. Here he is:

Is TSB the Best Bible Atlas ever? Yes, without question. Is it worth the price? Yes, certainly.

When it comes to biblical cartography and historical geography, it doesn’t get any better, more thorough, or more interesting than The Sacred Bridge.

Here is TSB‘s product page for more information. You can also find the atlas here through Eisenbrauns, its North American distributor. Accordance has it available electronically, as well.

TSB‘s younger sibling, Carta’s New Century Handbook and Atlas of the Bible, is here (Amazon), here (Carta), here (Eisenbrauns), or here (Accordance).

Many, many thanks to the fine folks at Carta and Eisenbrauns who set me up with a copy of TSB to review, both in print and Accordance. The publisher at Carta is one of the nicest and most interesting people with whom I’ve corresponded since starting Words on the Word more than two years ago.

excellent, detailed review Abram! this atlas looks amazing. what other Biblical atlas has terrain contour lines??

Thanks, David!

“Best” is a tricky word. A hammer is the best tool for driving a nail, but not a screw. TSB is a very well put together scholars’ atlas presenting discussion on finer points of historical geography. However, most lay people would find the discussion tedious. For example, your #4 Case Study The Gospels – TSB has a lengthy discussion of the location of Bethsaida. A very important and well put together discussion; and, a very tedious one for most lay people. I suggest (I’m biased ) for most lay persons that a better presentation of the historical geography of the gospels can be found in the seven full page maps of the Satellite Bible Atlas. http://www.bibleplaces.com/sba

(e.g., click on Look Inside > Private Galilean Ministry)

Hi, Bill! Well put. I tried to allude to that in my opening paragraph. You make good points, and I was actually just checking out your images and atlas yesterday, and adding it to my wish list. It looks great.

Your comment on the typesetting is perceptive, however there are other tricks up the typesetters sleeve other than changing the font colour. In that respect (at the risk of sounding churlish) I might say the page design lacks imagination. It’s very efficient, though. It is a very dense page with no “white space”, it appears intimidating. I cannot comment on content but just wanted to chip in with my opinion as a (semi-retired) professional typesetter of books and educational/training material. I’ve never seen this book and I only have the page you scanned to go on, so I don’t know if that is representative of the rest of the book. Best wishes!

Thanks for your comment, Alistair. A lot of the book is like the page I include here, as I recall. And revisiting this now with some distance, it is quite a dense page! I agree with your white space comment–this page is not exactly easy on the eyes.

DO NOT CLICK ON THIS LINK!!!! It is NOT an appropriate link. Somehow is has been changed or was a bad link to start with.

Hi, Betty! Thanks so much for calling this to my attention. I clicked through every single link on my blog post (which was a lot!) and found nothing untoward, but a Pingback at the very bottom (i.e., a post from someone else’s site that linked back here) made it through WordPress’s spam filters. So sorry you had that experience, and thanks again for letting me know! I have removed the offending link.